The artistic dialogue between Russia and Western Europe from the 18th century through the early 20th century reveals a complex story of adaptation, transformation, and radical innovation. While Russian artists initially absorbed European styles, they consistently reinterpreted them through distinctly Russian cultural, political, and spiritual filters. This process generated movements that bore superficial resemblances to their Western counterparts yet possessed fundamentally different philosophical underpinnings. The relationship was neither one of pure imitation nor complete independence, but rather a productive tension that pushed both Russian and European art into uncharted territory.

Quick Answer

Russian art movements absorbed European influences while transforming them through distinct cultural, political, and spiritual perspectives. From Peter the Great’s westernization through the Peredvizhniki’s social realism to the avant-garde’s radical abstraction, Russian artists consistently reinterpreted Western styles. The Peredvizhniki rejected academic Romanticism for socially conscious realism, while Suprematism and Constructivism took European Cubism and Futurism far beyond their original purposes, creating geometric abstraction that influenced global modernism. This exchange was bidirectional: Russian avant-garde innovations profoundly shaped Bauhaus, De Stijl, and American Minimalism, establishing Russian art as a transformative force in modern art history.

From Byzantine Icons to European Baroque: The Historical Foundation

The story begins with Russia’s isolation from Western European artistic developments for nearly seven centuries. While Renaissance humanism and later Baroque opulence swept through Italy, France, and the Low Countries, Russian art remained anchored in Byzantine icon painting traditions. The Orthodox Church maintained strict control over artistic production, prescribing forms and subjects that had changed little since the Christianization of Kievan Rus in 988 CE. Artists like Andrei Rublev (1360-1427) perfected these conventions, creating works of profound spiritual intensity within highly codified visual languages.

Peter the Great’s accession in 1682 initiated a dramatic rupture. Determined to modernize Russia along Western lines, Peter invited European artists to his new capital of St. Petersburg and sent promising Russian students to study in Italy, France, and Holland. The Russian Academy of Arts, established in 1757, explicitly promoted Neoclassical principles derived from French academic practice. Artists such as Dmitry Levitsky (1735-1822) and Vladimir Borovikovsky (1757-1825) produced portraits that would not have seemed out of place in Paris or London, adopting European conventions of pose, lighting, and psychological penetration.

Yet even at this early stage, differences emerged. Russian portraiture often retained the frontal, hieratic quality of icon painting beneath its European veneer. The spiritual intensity that characterized Byzantine religious art migrated into secular subjects. When Orest Kiprensky (1782-1836) painted portraits in the Romantic manner, his subjects possessed an inward-looking quality absent from the more extroverted portraits of his British contemporaries like Thomas Lawrence.

The Peredvizhniki: Redefining Realism for Russian Purposes

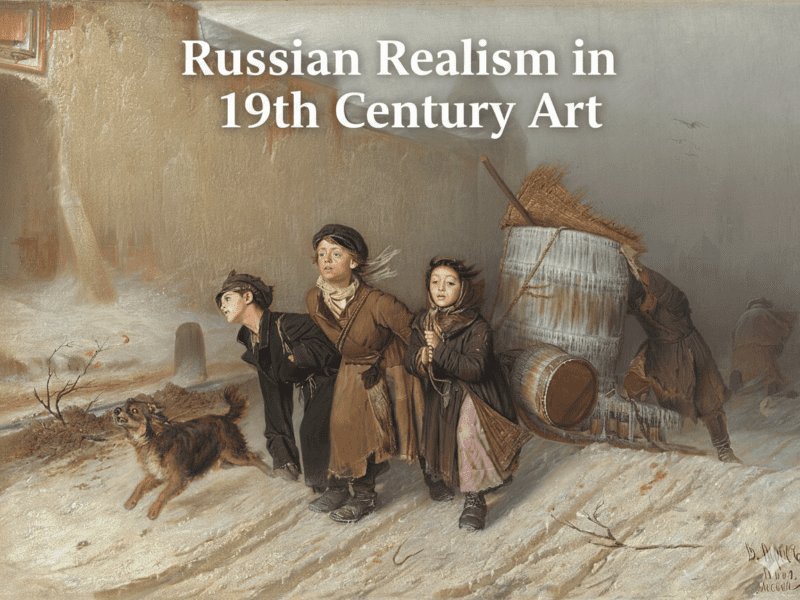

By the mid-19th century, Russian artists faced a choice between continuing to follow European models or developing a distinctly national school. The founding of the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) in 1870 marked the decisive turn toward the latter option. While European Realism, as practiced by Gustave Courbet in France, sought to depict contemporary life without idealization, the Peredvizhniki infused Realist techniques with explicit social criticism and moral purpose.

Ilya Repin (1844-1930) exemplifies this transformation. His painting “Barge Haulers on the Volga” (1870-1873) employs the observational accuracy of European Realism but directs it toward exposing the brutal exploitation of Russian peasants. The work’s composition, with its row of straining figures set against an indifferent horizon, serves a documentary and ethical function foreign to most French Realism. Repin studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris but returned to Russia convinced that art must serve social progress rather than aesthetic experimentation.

The Peredvizhniki also democratized art distribution in ways unprecedented in Europe. They organized traveling exhibitions that brought art to provincial cities, rejecting the St. Petersburg Academy’s monopoly on exhibition spaces. This mission to make art accessible to ordinary Russians paralleled the populist political movements of the 1870s. While European artists like Jean-François Millet painted peasants, they did so for urban bourgeois audiences; the Peredvizhniki sought to reach the peasants themselves.

Ivan Kramskoy (1837-1887), both artist and theoretician for the group, articulated principles that diverged sharply from European academic doctrine. Where French academic painting emphasized technical virtuosity and classical subjects, Kramskoy insisted on moral content and national relevance. His “Christ in the Desert” (1872) reimagines Jesus as a tormented Russian intellectual rather than an idealized Mediterranean figure, demonstrating how even religious subjects underwent transformation through Russian interpretation.

Parallel Paths: Romanticism and Symbolism East and West

Russian Romanticism arrived later than its Western European counterpart and bore distinctive characteristics shaped by Russian cultural conditions. While European Romanticism emphasized individual freedom and sublime nature, Russian Romantic painters like Karl Bryullov (1799-1852) combined these with narratives of historical catastrophe and collective suffering.

Bryullov’s “The Last Day of Pompeii” (1833), painted in Italy but exhibited to enormous acclaim in Russia, ostensibly follows European Romantic conventions established by artists like Eugène Delacroix. Yet Bryullov’s focus on the preservation of family bonds and religious faith amid destruction resonated with Russian audiences familiar with invasion and social upheaval in ways that French Revolutionary romanticism did not.

By the 1890s, Symbolism emerged in both Russia and Europe as a reaction against materialist realism. However, Russian Symbolism developed along markedly different lines from its French counterpart. Where French Symbolists like Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon drew on classical mythology and Christian mysticism filtered through decadent aesthetics, Russian Symbolists fused Orthodox spirituality with Slavic folklore.

Mikhail Vrubel (1856-1910) exemplifies this divergence. His “Pan” (1899) depicts the forest deity from Slavic mythology with a technical approach that breaks the picture plane into jewel-like facets. This technique, which Vrubel developed independently, has more in common with forthcoming Cubism than with contemporary European Symbolism. Vrubel studied medieval icons and Byzantine mosaics intensively, incorporating their spatial flatness and decorative surface treatment into ostensibly modern subjects.

The Blue Rose group, active 1904-1908, pursued a mystical Symbolism even more distant from European models. Artists like Pavel Kuznetsov (1878-1968) abandoned Western perspective and modeling almost entirely, creating dreamlike compositions where figures float in undefined spaces saturated with symbolic color. This approach anticipated aspects of Kandinsky’s early abstractions but remained rooted in specific Russian spiritual and cultural content.

💰 Did You Know?

When Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square” was first exhibited at the 0.10 Exhibition in Petrograd in 1915, he deliberately hung it in the corner of the room where Russian Orthodox icons traditionally occupied the “beautiful corner” of homes. This placement announced Suprematism as a new spiritual order replacing traditional religion, a gesture unimaginable in secular Western European avant-garde circles.

The Avant-Garde Explosion: From European Roots to Radical Departure

The early 20th century witnessed the most dramatic divergence between Russian and European art movements. Russian artists absorbed Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism with remarkable speed after 1910, but immediately pushed these styles toward more radical conclusions than their European originators had envisioned.

French Cubism, developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque after 1907, analyzed objects from multiple viewpoints while maintaining some connection to recognizable form. Russian Cubo-Futurism, pioneered by artists including Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962) and Mikhail Larionov (1881-1964), combined Cubist fragmentation with Italian Futurist dynamism and distinctly Russian primitivist elements drawn from folk art and icon painting.

Larionov’s Rayonism (1912-1914) went further, attempting to represent not objects but the rays of light reflecting between them. His “Rayonist Composition” (1912) presents a wholly non-objective field of intersecting diagonal lines and color planes. This preceded Kandinsky’s fully abstract paintings and represented one of the first completely non-representational art movements anywhere.

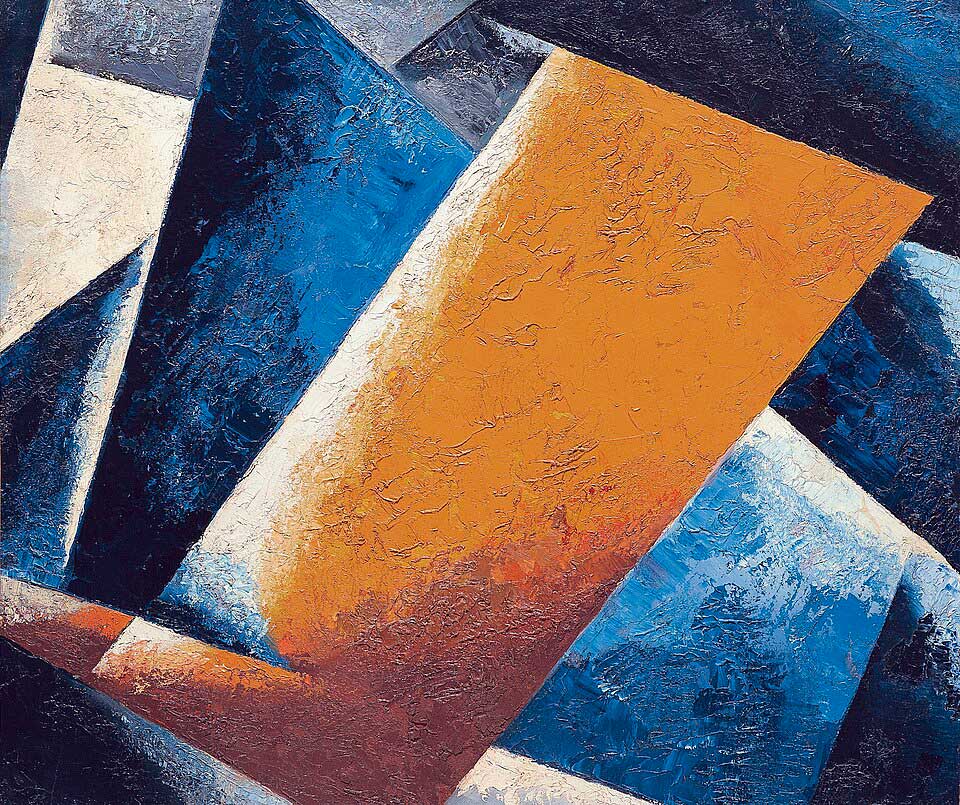

Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935) launched Suprematism in 1915, reducing painting to geometric forms in limited colors. His theoretical writings argued that art should abandon all connection to the material world to access pure feeling and spirituality. While this sounds similar to European abstract pioneers like Piet Mondrian, the philosophical foundations differed fundamentally. Mondrian sought universal harmonies based on theosophical principles; Malevich pursued what he termed “the supremacy of pure artistic feeling,” a concept rooted in Russian mystical traditions rather than Western esoteric philosophy.

Suprematism also differed crucially in its social ambitions. Malevich initially embraced the 1917 Revolution, believing Suprematism’s break with representational tradition paralleled the political break with tsarist oppression. He designed Suprematist teacups, textiles, and architectural models, attempting to remake everyday life through abstract forms. European abstraction, conversely, remained primarily a gallery and studio phenomenon until the Bauhaus adapted Russian ideas in the 1920s.

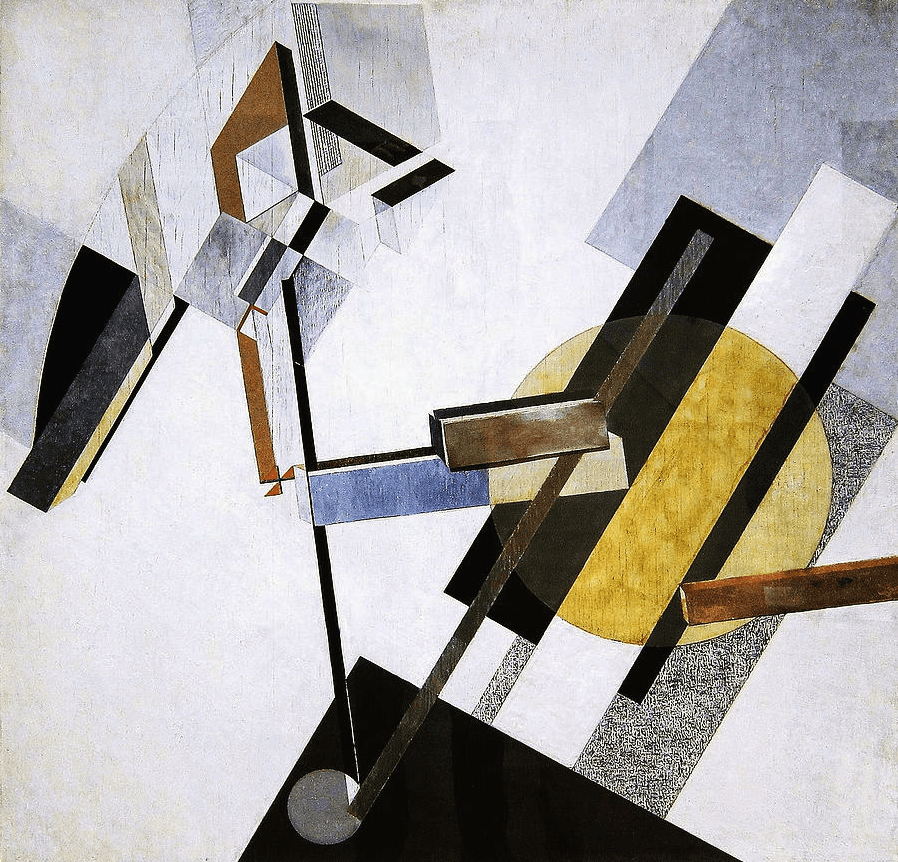

Constructivism, emerging around 1915-1920 through artists including Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953), Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956), and Lyubov Popova (1889-1924), took Cubism’s analytical approach and redirected it toward material investigation and social utility. Tatlin’s counter-reliefs, assembled from industrial materials like wood, metal, and glass, owed obvious debts to Cubist collage and construction. However, Constructivism’s insistence that art serve practical socialist purposes and its embrace of industrial materials and methods had no real European parallel until Russian ideas influenced the Bauhaus.

The Socialist Realism Interruption

By 1932, Stalin’s government mandated Socialist Realism as the only acceptable artistic style, effectively terminating avant-garde experimentation. Socialist Realism demanded easily legible images glorifying Soviet achievements and leaders, executed in 19th-century academic style. This represented a forced return to the kind of state-approved narrative painting that Russian artists had fought against since the Peredvizhniki rebellion.

Unlike earlier Russian styles that transformed European models, Socialist Realism was imposed from above by non-artists for explicitly political purposes. Its relationship to European precedents was Suprematismficial: it borrowed the technical means of 19th-century academic painting while stripping away any ambiguity or psychological complexity. Works like Isaak Brodsky’s “Lenin at Smolny” (1930) demonstrate competent but utterly conventional technique in service of propaganda.

The Socialist Realist period did, however, produce a peculiar inversion of the Russian-European relationship. While official Soviet art stagnated in academic conservatism, underground artists developed Nonconformist styles often directly inspired by Western modernism. When Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933) and other Nonconformists finally emerged in the 1960s-1980s, they created work that synthesized European conceptualism with specifically Soviet experiences, reversing the earlier pattern where Russian artists transformed European styles.

Mutual Influences: How Russian Art Reshaped European Modernism

The Russian-European exchange was never unidirectional. From the 1910s onward, Russian innovations profoundly influenced European and later American art. Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), though he lived primarily in Germany after 1896, maintained deep Russian cultural roots that shaped his pioneering abstract paintings. His “Composition VII” (1913) combined the spiritual concerns of Russian Symbolism with technical lessons from German Expressionism, creating a synthesis that influenced artists across Europe.

The Bauhaus, founded in Germany in 1919, absorbed Russian Constructivist ideas wholesale after several Russian artists including El Lissitzky (1890-1941) established direct contacts. László Moholy-Nagy’s light-space modulators and Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel furniture owe obvious debts to Constructivist prototypes. The Bauhaus slogan “art and technology, a new unity” directly echoed Constructivist manifestos.

De Stijl in the Netherlands, founded by Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg, developed geometric abstraction parallel to Suprematism. While both movements pursued reduction to essential forms and colors, De Stijl emphasized horizontal-vertical balance based on universal principles, while Suprematism sought dynamic asymmetry expressing spiritual energy. Nevertheless, exhibitions of Russian avant-garde work in Western Europe in the 1920s clearly influenced De Stijl’s evolution toward greater simplification.

American Abstract Expressionism of the 1940s-1950s and Minimalism of the 1960s represent longer-term influences. Mark Rothko’s color field paintings echo Malevich’s pursuit of pure emotional effect through color and form, while Donald Judd’s serial metal boxes recall Rodchenko’s spatial constructions. These American artists knew Russian avant-garde work primarily through museum exhibitions and publications, demonstrating how decisively Russian innovations had entered the modernist canon.

Technical Approaches: Surface, Space, and Material

Comparing technical methods reveals fundamental differences in how Russian and European artists conceived painting’s purpose. European academic tradition, dominant through the 19th century, emphasized illusionistic three-dimensional space created through linear perspective, atmospheric effects, and carefully graduated modeling of form. Even when Impressionists challenged academic conventions, they retained the window-into-depth spatial model.

Russian artists, influenced by icon painting’s flat, frontal compositions, often resisted deep illusionistic space even when working in ostensibly Western styles. Vrubel’s “Demon Seated” (1890) appears to depict a three-dimensional figure, yet close examination reveals that background and figure occupy the same picture plane, assembled from similar faceted brushstrokes. This flattening tendency, rooted in centuries of icon painting, made Russian artists particularly receptive to Cubist spatial ambiguity.

Material treatment also differed. European oil painting technique traditionally aimed for smooth, refined surfaces that concealed the painter’s process. Even Impressionist broken brushwork served optical goals of representing light. Russian artists, particularly after 1900, often emphasized paint’s material presence. Vrubel applied paint with palette knives in thick, crystalline forms. Larionov’s Rayonist paintings feature aggressive, almost violent brushstrokes that assert the painting’s existence as a physical object rather than a transparent window.

Constructivism took this materiality furthest, abandoning traditional easel painting for assemblages of wood, metal, glass, and industrial materials. Tatlin’s counter-reliefs, constructed from scavenged materials, rejected European painting’s privileging of optical experience, demanding instead that viewers confront objects occupying real space. This approach anticipated European movements like Arte Povera by four decades.

Spiritual vs. Formal: Underlying Philosophical Divergences

Perhaps the deepest distinction between Russian and European art movements lies in their philosophical orientations. Western European modernism, despite enormous internal variations, generally emphasized formal innovation and visual experience. French Cubism analyzed form; Italian Futurism celebrated modern dynamism; Dada attacked bourgeois values. Even Symbolism, despite its spiritual pretensions, functioned primarily as a late Romantic retreat from modern life.

Russian art movements consistently embedded formal innovation within larger spiritual, social, or philosophical frameworks. The Peredvizhniki viewed technical competence as meaningless without moral content. Symbolists like Vrubel pursued mystical states through visual form. Suprematists sought to express “pure feeling” unmediated by recognizable objects. Constructivists dedicated art to building socialist society.

This difference reflects broader cultural patterns. Russian intellectual life in the 19th and early 20th centuries was dominated by questions of national identity, social justice, and spiritual meaning in ways that had no Western European equivalent. Russian literature from Dostoevsky to Tolstoy wrestled with ultimate questions of existence and morality; Russian art could not remain content with purely formal concerns.

Malevich’s writings exemplify this. He discussed Suprematism not as an artistic style but as a path to cosmic consciousness, comparing it to religious enlightenment. Such rhetoric would seem absurd in the mouths of French Cubists, who discussed their work in terms of visual structure and pictorial organization. When Mondrian wrote theoretically, he invoked universal harmonies and theosophical principles, but his goal remained creating balanced compositions. Malevich aimed at nothing less than spiritual transformation.

The Legacy: How Comparison Enriches Understanding

Examining Russian art movements in relation to European counterparts illuminates both more clearly. Russian artists were neither passive recipients of European influence nor completely independent inventors. They engaged actively with Western European art, selectively adopting techniques while transforming them to serve distinctly Russian purposes shaped by Orthodox spirituality, social consciousness, and eventually revolutionary politics.

This pattern of transformation rather than imitation explains why Russian avant-garde movements proved more influential than contemporaneous European developments in some respects. Suprematism’s radical reduction of form and Constructivism’s integration of art with social purpose offered more extreme positions that subsequent artists could build upon or react against. The Bauhaus, De Stijl, and American Minimalism all acknowledged debts to Russian sources, demonstrating that the margins can reshape the center.

Understanding these comparisons also contextualizes periodic claims that Russian artists merely copied European models. While Russian artists certainly learned from European sources, the resulting works differed sufficiently to constitute original contributions. The Peredvizhniki transformed Realism into social critique; Vrubel created a Symbolism fused with Orthodox mysticism; Malevich and Tatlin pushed abstraction far beyond Cubist precedents.

Contemporary Russian art continues navigating relationships with Western European and American art worlds. Post-Soviet artists often create work engaging both Russian historical legacies and international contemporary discourse, maintaining the pattern of selective engagement and transformation that characterized earlier Russian-European artistic dialogues.

Essential Points About Russian vs. European Art Movements

- Russian art movements consistently absorbed European influences while transforming them through distinct cultural, spiritual, and political perspectives, creating original styles rather than mere imitations.

- The Peredvizhniki redirected European Realism toward explicit social criticism and democratic art distribution, making art accessible to provincial audiences rather than urban elites.

- Russian Symbolism fused Orthodox spirituality and Slavic folklore with European Symbolist techniques, creating mystical works distinct from French Symbolism’s classical and decadent themes.

- Suprematism and Constructivism pushed European Cubism and Futurism toward radical conclusions their originators never envisioned, pursuing complete abstraction and social utility respectively.

- Technical approaches differed fundamentally: Russian artists’ icon painting heritage made them emphasize flat surfaces and material presence versus European illusionistic depth and refined surfaces.

- Philosophical foundations diverged sharply, with Russian movements embedding formal innovation within spiritual, social, or philosophical frameworks versus European modernism’s emphasis on formal experimentation.

- The exchange proved bidirectional: Russian avant-garde innovations profoundly influenced Bauhaus, De Stijl, American Abstract Expressionism, and Minimalism, reshaping global modernism.

- Socialist Realism (1932-1980s) represented a forced interruption imposed by political authorities, unlike organically developed Russian styles that transformed European models.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Q – How did Russian Realism differ from European Realism?

- A – While European Realism sought objective depiction of contemporary life, Russian Realism through the Peredvizhniki movement added explicit social criticism and moral purpose. Artists like Ilya Repin used Realist techniques to expose social injustices and advocate for reform, organizing traveling exhibitions to reach provincial audiences rather than limiting art to urban galleries. This ethical dimension and democratic mission distinguished Russian from European Realist practice.

- Q – Why did Russian avant-garde movements develop more radical abstraction than European Cubism?

- A – Russian artists pushed abstraction further because they approached it through spiritual and philosophical frameworks rather than purely formal analysis. Malevich’s Suprematism sought to express pure feeling and cosmic consciousness, while Constructivists aimed to remake society through new forms. Their icon painting heritage, emphasizing flat surfaces and spiritual content, also made complete abstraction more conceptually accessible than for European artists trained in illusionistic Western traditions.

- Q – What technical characteristics distinguished Russian Symbolist painting from French Symbolism?

- A – Russian Symbolists like Mikhail Vrubel developed faceted, crystalline brushwork applied with palette knives, breaking forms into jewel-like planes that anticipated Cubism. This technique derived from studying Byzantine mosaics and Persian carpets, emphasizing surface decoration over illusionistic depth. French Symbolists maintained more traditional painting techniques despite their mystical subjects. Russian Symbolism also fused Orthodox spirituality with Slavic folklore rather than relying on classical mythology and Christian iconography filtered through decadent aesthetics.

- Q – How did Russian Constructivism influence European design movements?

- A – Russian Constructivism profoundly shaped the Bauhaus through direct contact between Russian artists like El Lissitzky and Bauhaus faculty in the 1920s. Constructivist principles of integrating art with industrial production, using modern materials, and creating socially useful designs became central Bauhaus tenets. László Moholy-Nagy’s light sculptures and Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel furniture directly adapted Constructivist prototypes. The movement also influenced De Stijl and later American Minimalism through exhibitions and publications.

- Q – Where can I see major Russian avant-garde works today?

- A – The State Tretyakov Gallery and State Russian Museum in Russia hold the largest collections of Russian avant-garde art. Major Western museums with significant holdings include the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which owns important Suprematist and Constructivist works, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam with extensive Malevich holdings, and the Guggenheim Museum which features Kandinsky’s pioneering abstractions. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Norton Simon Museum also possess notable Russian avant-garde pieces.