Between Byzantine mosaics and Buddhist philosophy, Russian art occupies a unique position on the world’s cultural map. For centuries, artists working within the vast Russian Empire absorbed influences from Constantinople, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and beyond, creating works that challenge simple categorization as either “Eastern” or “Western.” This cross-pollination of artistic traditions produced some of the most distinctive and thought-provoking movements in art history, from the ornate religious iconography of medieval Rus’ to the experimental canvases of early 20th-century modernists.

Russian cultural production has always existed at a crossroads. Geography made this inevitable. Stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Pacific Ocean, the Russian Empire encompassed Orthodox Christians and Muslims, Slavs and Turkic peoples, European academies and Asian trade routes. Artists did not merely observe these diverse traditions from a distance. They traveled to Samarkand and Tbilisi, studied Persian miniatures, incorporated Japanese prints into their compositions, and wrestled with questions about their own identity in the process.

Quick Answer

Russian art represents a unique synthesis of Eastern and Western traditions, shaped by the empire’s geographic position between Europe and Asia. From Byzantine religious iconography adopted in 988 CE to 19th-century Orientalist movements and early modernist experiments, Russian artists continuously absorbed and transformed influences from Constantinople, Central Asia, Persia, and Japan. This cultural hybridity produced distinctive movements like the Neo-Russian style and Russian Orientalism, where artists grappled with questions of national identity while creating works that transcended simple East-West categorization.

The Byzantine Foundation: Where Russian Art Begins

The adoption of Eastern Orthodox Christianity in 988 CE under Prince Vladimir of Kievan Rus’ fundamentally altered the trajectory of Russian visual culture. Byzantine masters arrived from Constantinople, bringing with them centuries of refined techniques for creating religious icons and adorning churches with frescoes. These images followed strict conventions inherited from ancient Greek and Roman art, filtered through Christian theology and Eastern aesthetic sensibilities.

Icon painting became the dominant art form for the next seven centuries. Unlike Western European religious art, which moved progressively toward naturalism and perspective, Russian icons maintained the flat, gold-backed, spiritually charged style of their Byzantine predecessors. Figures appeared elongated, faces solemn and otherworldly. The icon was not meant to be a window onto physical reality but rather a portal to the divine.

Yet even within this conservative tradition, Russian artists developed their own distinct approach. By the 15th century, painters like Andrei Rublev had softened the austere Byzantine palette, introducing gentler colors and greater emotional depth. The State Russian Museum houses examples showing how Slavic sensibilities gradually transformed imported Byzantine models into something recognizably Russian.

Peter’s Window: The First Great Western Turn

When Peter the Great assumed power in 1682, he embarked on an aggressive program of Westernization that would shake Russian culture to its foundations. Peter had traveled incognito through Western Europe, working in Dutch shipyards and visiting artists’ studios. He returned convinced that Russia must abandon its isolation and embrace European methods in everything from military organization to artistic production.

Foreign artists flooded into the newly founded city of St. Petersburg. Italian architects designed Baroque palaces. Dutch painters taught Russian students the techniques of portraiture and landscape painting developed in Amsterdam and Antwerp. The Imperial Academy of Arts, established in 1757, trained artists in the Neoclassical style then fashionable across Europe.

This wholesale adoption of Western forms created tension. Some embraced the modernization as necessary progress. Others saw it as a betrayal of authentic Russian traditions. This debate about national identity versus cosmopolitan sophistication would echo through Russian art for the next two centuries, never fully resolved.

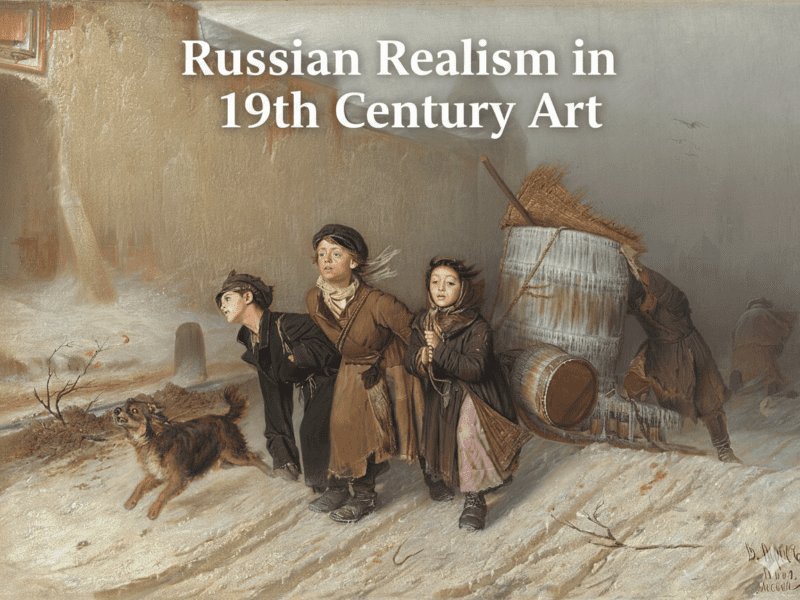

The Oriental Turn: Discovering the Empire’s Eastern Territories

As the 19th century progressed, Russian artists began looking eastward with fresh eyes. The empire’s conquests in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Siberia brought millions of Muslim and Buddhist subjects under tsarist rule. Unlike Western European Orientalists who traveled to “exotic” lands as tourists or colonizers of distant territories, Russian artists engaged with the East as part of their own empire’s internal geography.

This created what scholars call the “paradox of Russian Orientalism.” Were Central Asian Muslims the colonized “other,” or were they fellow subjects of the same empire? The Russian saying “scratch a Russian and you’ll find a Tatar” (referring to the Mongol invasions of medieval Rus’) suggested deep historical connections. Yet imperial administrators often treated conquered territories with the same civilizing mission rhetoric employed by British and French colonialists.

Artists responded to this ambiguity in diverse ways. Vasily Vereshchagin traveled with Russian military campaigns to Central Asia in the 1860s and 1870s, producing hundreds of paintings depicting both the violence of conquest and the beauty of Islamic architecture. His “Turkestan Series” showed Samarkand’s turquoise-tiled mosques and madrassas with ethnographic precision, while his war paintings challenged the glory typically attributed to military victories.

Other artists approached Eastern themes through the lens of spirituality and aesthetic renewal. The World of Art (Mir Iskusstva) movement, founded in the 1890s, included artists who drew inspiration from Persian miniatures, Japanese prints, and Russian folk art in equal measure. They saw no contradiction in synthesizing these influences. For them, art transcended national boundaries.

Nicholas Roerich: The Ultimate Cultural Bridge

Few artists embodied East-West fusion more completely than Nicholas Roerich (1874-1947). Trained in St. Petersburg’s Imperial Academy, Roerich began his career designing theatrical sets that drew on medieval Russian history and Slavic mythology. His Neo-Russian style incorporated the flattened perspectives and bold colors of traditional icon painting into modern compositions.

But Roerich’s interests extended far beyond Russia’s Slavic past. In the 1910s, he and his wife Helena became deeply involved in Theosophy and Eastern religions. They studied Hindu and Buddhist philosophy, convinced that ancient spiritual wisdom could revitalize modern civilization. When revolution convulsed Russia in 1917, the Roerichs eventually settled in India’s Kullu Valley, where Nicholas spent his final decades painting the Himalayas and promoting his vision of universal spirituality.

Roerich’s Himalayan paintings synthesize his Russian training with Asian subject matter and spiritual philosophy. The mountain peaks glow with the same transcendent light found in Byzantine icons, yet the compositions reflect his study of Tibetan Buddhist art. He designed sets for Buddhist temples in St. Petersburg and proposed an international treaty (the Roerich Pact) to protect cultural heritage during wartime, seeing art as a bridge between nations.

💰 Did You Know?

Catherine the Great was so enamored with Chinese art that she commissioned entire rooms in her palaces decorated in the chinoiserie style. The Chinese Drawing Room at Oranienbaum palace, completed in the 1760s, features imported lacquer panels, silk wallpaper, and porcelain collections that demonstrate Russia’s fascination with East Asian aesthetics long before the better-known Japonisme movement of the late 19th century.

Pavel Kuznetsov and the Blue Rose: Central Asian Modernism

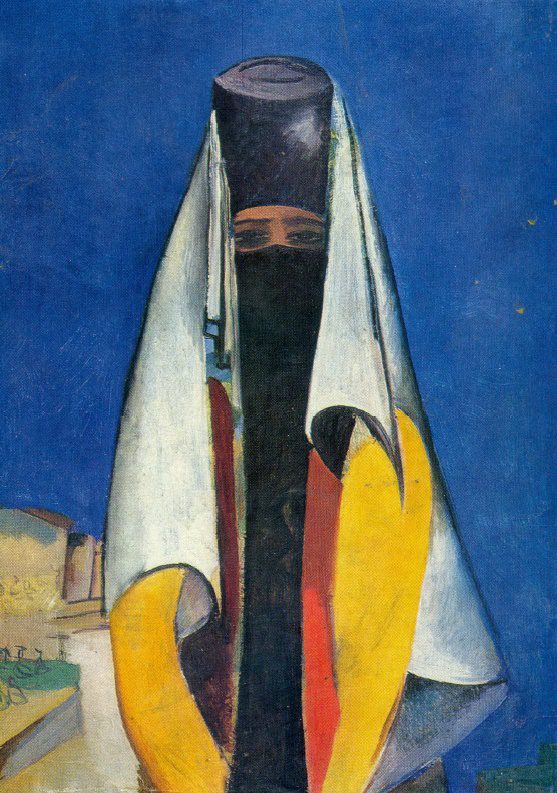

The early 20th century saw Russian modernists making pilgrimages to Central Asia in search of artistic renewal. Pavel Kuznetsov (1878-1968), a leading member of the Blue Rose group of Symbolist painters, traveled repeatedly to the steppes of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan between 1912 and 1928. There he painted pastoral scenes of agricultural workers, nomadic camps, and vast desert expanses.

Kuznetsov’s Central Asian works employ a muted palette of dusty pinks, pale blues, and sandy yellows. His style synthesizes Post-Impressionist color theory learned from French painting with the flattened spatial organization of Persian miniatures. Figures appear simplified almost to the point of abstraction, yet retain identifiable cultural markers like traditional clothing and architectural details.

What distinguishes Kuznetsov’s Orientalism from his Western European counterparts is his attempt to capture an essential spiritual quality rather than exotic surface details. He wrote about seeking “distant and strange” visions that could transport viewers beyond material reality. This mystical approach owed as much to Symbolist poetry and Russian Orthodox spirituality as it did to the Buddhist and Islamic cultures he encountered in Central Asia.

Natalia Goncharova: Primitivism Meets Futurism

Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962) represents another strand of Russian cultural fusion. A leading figure in the Moscow avant-garde, Goncharova deliberately rejected Western European artistic dominance, declaring that Russian and Asian art offered superior alternatives. Her manifestos proclaimed: “Contemporary Western ideas can no longer be of any use to us.”

Yet Goncharova’s “Eastern” influences were extraordinarily diverse. She studied icon painting, Japanese woodblock prints, Persian miniatures, and Russian folk art (lubok prints). Her paintings incorporated all of these sources simultaneously. “Peacocks” (1911) shows birds rendered in a style combining the gold backgrounds of icons with the flat color planes of Japanese prints and the stylized forms of Persian painting.

Goncharova’s primitivism was not about returning to some imagined pure past. Instead, she selectively borrowed formal elements from various non-Western traditions to challenge the assumption that artistic progress moved in a straight line from Renaissance naturalism to modern European styles. By placing ancient Russian icon painting and contemporary Cubism in dialogue, she argued that multiple artistic traditions could coexist and inform each other.

The Neo-Russian Style: Folklore Meets Modernism

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a revival of interest in Russian peasant crafts and folk traditions. This movement, closely related to the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain, sought to preserve disappearing artisanal techniques in an age of industrialization. The Abramtsevo artists’ colony, founded in 1878 near Moscow, became a center for this Neo-Russian style.

Artists working at Abramtsevo studied traditional embroidery patterns, woodcarving, and ceramic techniques. They incorporated these folk motifs into modern paintings, theatrical designs, and decorative arts. Viktor Vasnetsov created fairy-tale scenes populated by Russian folk heroes like Bogatyrs (knight-errants), while Mikhail Vrubel fused Byzantine mosaic techniques with Art Nouveau’s flowing lines.

The Neo-Russian style represented a form of cultural fusion that looked inward rather than outward. Yet it still involved synthesis. These artists combined folk traditions with modern European movements like Symbolism and Art Nouveau. They worked across multiple media, designing furniture, architecture, textiles, and stage sets alongside easel paintings. This multimedia approach would profoundly influence the Ballets Russes productions that introduced Russian art to Western Europe in the 1910s.

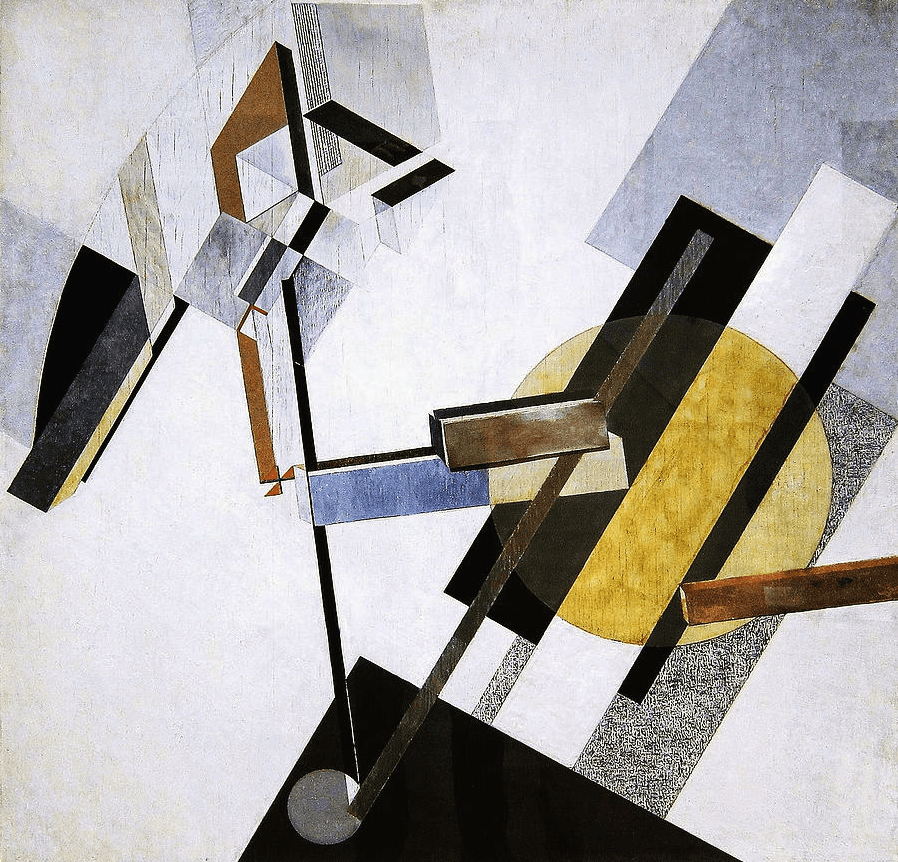

Constructivism and the International Avant-Garde

The Russian Revolution of 1917 brought another dramatic shift. The early Soviet period saw artists attempting to create an entirely new visual language suitable for a socialist society. Constructivists like Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko rejected easel painting altogether, focusing instead on industrial design, typography, and utilitarian objects.

Yet even this supposedly anti-traditional movement drew on diverse cultural sources. Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist paintings, with their floating geometric forms, were influenced not only by European Cubism but also by his study of Zen Buddhism. Malevich wrote about seeking the “zero of form,” a concept resonating with Buddhist ideas of emptiness and transcendence. His “Black Square” (1915) functions like an icon, demanding contemplation rather than representational reading.

The Russian avant-garde existed within international networks. Artists traveled between Moscow, Berlin, and Paris. They collaborated with Dutch De Stijl, German Bauhaus, and Italian Futurist movements. El Lissitzky’s typographic innovations influenced modernist design globally. This was cultural fusion on a truly international scale, with Russian artists contributing to and drawing from a broader European modernist conversation.

The Ballets Russes: Exporting Cultural Synthesis

Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes (1909-1929) became the most visible ambassador for Russian cultural fusion in Western Europe. The productions synthesized music by Stravinsky and Prokofiev, choreography by Nijinsky and Fokine, and set designs by Bakst, Benois, and Goncharova. These collaborations drew freely on Russian folklore, Eastern exoticism, and modernist abstraction.

Léon Bakst’s costume designs for productions like “Scheherazade” (1910) combined Persian and Central Asian motifs with Art Nouveau’s decorative excess. The vivid colors and sensual fabrics shocked Parisian audiences accustomed to more restrained theatrical design. Yet these “Oriental” elements were filtered through a distinctly Russian sensibility, creating something that was neither purely Eastern nor Western.

The Ballets Russes demonstrated how Russian artists had absorbed influences from across Eurasia and synthesized them into original creations. Western Europeans saw these productions as thrillingly exotic, not realizing they were viewing a highly sophisticated cultural fusion that reflected Russia’s complex relationship with both European and Asian traditions.

Common Misunderstandings About Russian Cultural Fusion

“Russian Art Simply Copied from Byzantium”

While Byzantine influence was foundational, Russian artists transformed imported models within generations. The softened palette, increased emotional expressiveness, and distinctive iconographic types developed by 15th-century Russian masters represent original contributions, not mere copying. Later periods saw even more dramatic departures from Byzantine prototypes.

“Orientalism in Russia Was the Same as in France or Britain”

Russian Orientalism differed fundamentally from Western European versions because the “Orient” was part of Russia’s own empire and history. Russian artists often had more sustained engagement with Central Asian and Caucasian cultures, sometimes living in these regions for years. The relationship between colonizer and colonized was more ambiguous given Russia’s own contested position between Europe and Asia.

“Soviet Art Rejected All Traditional Influences”

While Stalin-era Socialist Realism imposed strict restrictions, early Soviet artists drew on diverse historical sources. Malevich studied icon painting and Eastern philosophy. Soviet propaganda posters in 1920s Uzbekistan incorporated Islamic art traditions. Even during the most repressive periods, underground artists maintained connections to both Russian and international artistic traditions.

The Modern Legacy: Continuing Conversations

Contemporary Russian artists continue to engage with this heritage of cultural fusion. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 opened new possibilities for international exchange while also prompting fresh examinations of Russian identity. Artists like Ilya Kabakov, Erik Bulatov, and the AES+F group create works that reference Soviet history, Orthodox traditions, Asian philosophies, and global contemporary art in complex combinations.

The question “What makes art Russian?” remains as contested today as it was in Peter the Great’s time or during the World of Art movement’s heyday. Is it subject matter? Technique? Spiritual sensibility? Or something else entirely? The richest answer may be that Russian art’s defining characteristic is precisely this ongoing negotiation between diverse cultural influences, the refusal to settle into a single, stable identity.

Museums worldwide now recognize the importance of Russian art’s hybrid character. The State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the Museum of Modern Art in New York present Russian works not as isolated national productions but as part of interconnected global conversations. Exhibitions like “Russia’s Unknown Orient” (2010) and “Russian Orientalism in a Global Context” (2022) have explored these themes in scholarly depth.

Related Movements and Cross-Pollinations

Russian art’s fusion tendencies connect to several international movements. The Neo-Russian style paralleled Britain’s Arts and Crafts movement and Scandinavia’s National Romantic style in seeking modern applications for folk traditions. Russian Symbolism shared spiritual concerns with French Symbolists while drawing on different mystical sources. The Russian avant-garde participated fully in international modernism while contributing distinctive elements like Suprematism and Rayonism.

Japanese art influenced Russian artists as profoundly as it did French Impressionists, though often through different channels. Goncharova and Larionov studied Japanese prints collected by Moscow merchants involved in Asian trade. The Princess Tenisheva’s collection at Talashkino included East Asian art alongside Russian folk crafts, encouraging artists to see connections between different non-Western traditions.

Chinese art also left traces in Russian visual culture, from Catherine the Great’s chinoiserie rooms to Soviet propaganda posters incorporating calligraphic elements in the 1920s. The Silk Road trade routes that passed through Central Asian territories under Russian control facilitated artistic exchange for centuries before modern ethnographic study began.

Essential Points About East-West Fusion in Russian Art

- Russian art’s hybrid character stems from geographic and historical factors, particularly the empire’s position spanning Europe and Asia

- Byzantine Christianity provided the foundational aesthetic from 988 CE, but Russian artists developed distinctive approaches within this tradition

- Peter the Great’s Westernization program (1682-1725) created tensions between European and traditional Russian artistic values that persisted for centuries

- Nineteenth-century Russian Orientalism differed from Western European versions due to Russia’s ambiguous position as both European power and semi-Asian empire

- Artists like Nicholas Roerich and Pavel Kuznetsov synthesized Russian training with extended engagement with Central Asian and Himalayan cultures

- The Neo-Russian style and Mir Iskusstva movement deliberately combined folk traditions with modern European artistic innovations

- Early Soviet avant-garde artists drew on Eastern philosophy (Buddhism, Zen) alongside Western modernist movements

- The Ballets Russes exported Russian cultural fusion to Western Europe, where it was often misunderstood as purely exotic Orientalism

Frequently Asked Questions

- Q – What defines Russian cultural fusion in art?

- A – Russian cultural fusion refers to the synthesis of Byzantine, European, and Asian influences that characterizes Russian art across centuries. This hybrid quality emerged from Russia’s geographic position between Europe and Asia, its adoption of Byzantine Christianity, and centuries of interaction with neighboring cultures. Artists absorbed techniques and motifs from Constantinople, Central Asia, Persia, Japan, and Western Europe, creating works that transcend simple East-West categorization.

- Q – How did Peter the Great change Russian art?

- A – Peter the Great’s Westernization program (1682-1725) fundamentally transformed Russian art by importing European styles and techniques. He invited foreign artists to St. Petersburg, sent Russian students to study in Western Europe, and established institutions like the Imperial Academy of Arts. This created lasting tension between traditional Russian aesthetic values and European artistic conventions, a debate that would shape Russian art for the next two centuries.

- Q – Why is Russian Orientalism different from French or British Orientalism?

- A – Russian Orientalism differs because the ‘Orient’ was part of Russia’s own empire rather than distant foreign lands. Russian artists often lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, or Siberia for extended periods as part of military campaigns or administrative service. Additionally, Russia’s contested identity between Europe and Asia made the relationship between self and other more ambiguous than in Western European Orientalism, where clear distinctions existed between colonizer and colonized.

- Q – Which Russian artist best exemplifies East-West fusion?

- A – Nicholas Roerich (1874-1947) exemplifies East-West fusion most completely. Trained in St. Petersburg’s Imperial Academy, he drew on medieval Russian history and Slavic mythology before becoming deeply involved in Hindu and Buddhist philosophy. After settling in India’s Kullu Valley, Roerich painted Himalayan landscapes that synthesized Russian icon painting traditions with Tibetan Buddhist art and his own spiritual philosophy, creating works that truly bridged multiple cultural traditions.

- Q – Where can I see major Russian fusion artworks today?

- A – The State Tretyakov Gallery and State Russian Museum in Moscow and St. Petersburg house the most comprehensive collections of Russian art showing cultural fusion. International institutions like the Museum of Modern Art in New York and various European museums also hold significant Russian avant-garde and Orientalist works. Recent exhibitions like ‘Russia’s Unknown Orient’ have specifically focused on documenting this hybrid artistic tradition for contemporary audiences.