Russian still life painting transformed from a humble “lower” genre to revolutionary artistic expression that changed everything we thought we knew about arrangement and meaning. From the first Russian still lifes in the 18th century to the record-breaking auction prices of today, this artistic tradition reveals the soul of a nation through carefully arranged objects.

The Birth of Russian Still Life: From Academic Exercise to Art Form

Still life as an independent genre didn’t appear in Russia until the beginning of the 18th century. Before this, the genre was considered vastly inferior to portrait and historical paintings – relegated to academic exercises that focused mainly on “the art of flowers and fruit”.

Ivan Khrutsky became the first Russian artist to truly discover the charm of the genre, though his work remained oriented toward salon academic art. His breakthrough came when he moved from simple compositions of several objects to large still lifes with elaborate structures and great variety of elements.

The real transformation happened in the 19th century when artists like Vasily Polenov and Pavel Fedotov began incorporating still life elements into their compositions with deeper meaningfulness. However, these remained just parts of larger works rather than independent artistic statements.

The Impressionist Revolution: How French Influence Changed Everything

The genuine interest in still life emerged alongside collections of French paintings brought to Russia by major art patrons. French impressionism and impressionist still life specifically boosted curiosity for the style and contributed Russian artists’ names to the world treasury.

While Isaac Levitan still adhered to certain canons like isolated objects and neutral backgrounds, artists like Valentin Serov and Konstantin Korovin revealed a distinctive new trend: attempting to combine wild nature with inanimate objects. Still life began merging with interior scenes, was brought outdoors, and filled with human mood and emotions.

Igor Grabar became another significant representative of “Russian impressionism” who made considerable contributions to the genre. The artist admitted being influenced by Claude Monet and other impressionists, particularly in his 1905 works “Lilac and forget-me-nots” and “Chrysanthemums”. However, he strived to overcome the obvious narrowness of the style by complicating tasks and searching for new artistic expression means.

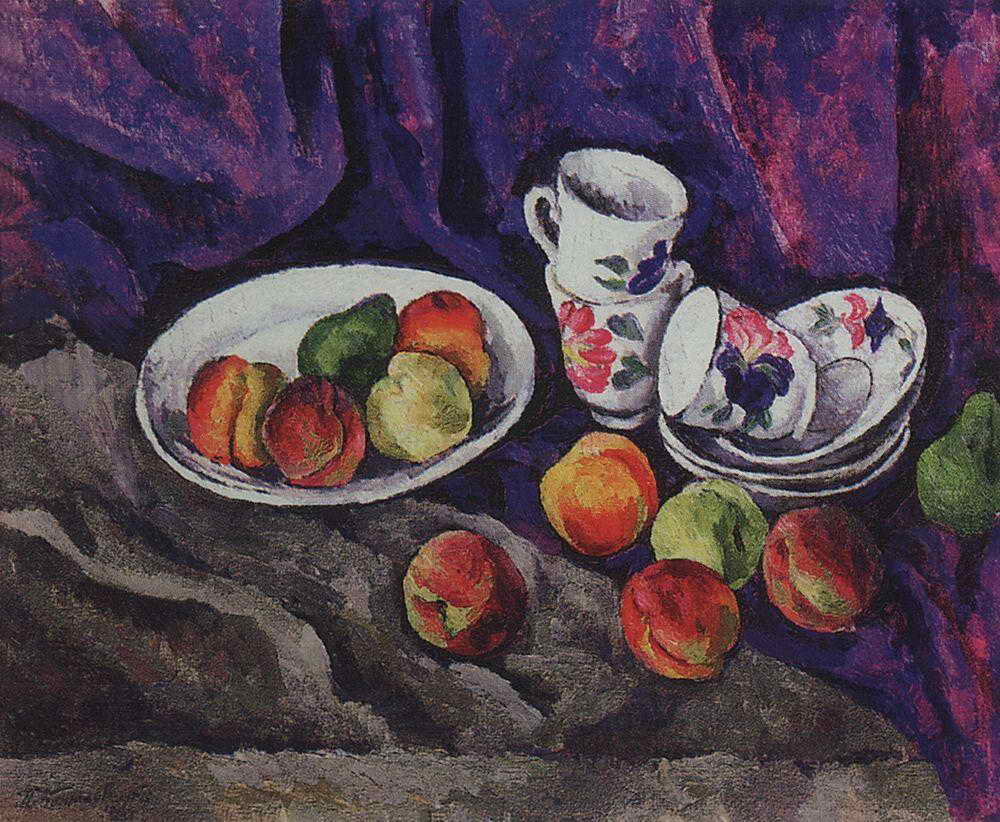

Grabar’s work reached its peak in 1903-1907 and was notable for a peculiar divisionist painting technique bordering on pointillism. His “Still Life with Apples and a Black Shawl” from around 1900 demonstrates masterful handling of texture, visible in the palpable plumpness of ripe fruit and the delicacy with which he portrays highlights and reflections.

The Revolutionary Period: When Objects Became Political

The beginning of the 20th century saw the flowering of Russian still life painting, gaining equality among other genres for the first time. Artists actively searched in the field of color, form, and composition, with all of this being especially evident in still life work. Enriched with new themes, images, and artistic techniques, Russian still life developed extraordinarily fast – in fifteen years it went from impressionism to abstract shapes.

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin emerged as a unique artist who reflected on the genre of “motionless models” in ways that can hardly be called “still” or “dead”. His creations featured frugal sets of objects, tense rhythm, and stern composition. Petrov-Vodkin conveyed the philosophy of his time through color and unexpected perspective.

Petrov-Vodkin developed his revolutionary “spherical perspective” – a unique twist that distorted drawing to represent the viewer high enough to notice the spherical curve of the globe. He used this extensively in works that make the observer seem more distant but actually closer. This technique built upon Byzantine perspective – an inverted perspective used in iconography.

His 1928 “Still Life with Lilac” sold for a world record £9,286,250, becoming the most expensive painting ever at a Russian art auction. Painted at the height of his career, this work embodies the artist’s foray into the science of optics. The focal point features a freshly cut branch of blooming lilac creating spontaneous shapes that counterweigh the rigorous definition of manmade objects.

The Knave of Diamonds: Rebels with Brushes

The Knave of Diamonds group, founded in Moscow in 1910, became a crucial avant-garde circle whose members were the leading exponents of revolutionary art in Russia. Named for their inaugural exhibition, the group’s intention was to provoke the art establishment, challenge “good taste,” and shock audiences.

The group included Robert Falk, Natalya Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Aristarkh Lentulov, Aleksandr Kuprin, Pyotr Konchalovsky, and Ilya Mashkov. They displayed portraits and still lifes strongly influenced by French artists Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse.

These artists sought “to unite the stylistic system of Cézanne with the primitive traditions of folk art, the Russian lubok (popular prints) and tradesman’s signs”. Their aim was returning to the roots of Russian folk art, to originality and “ignorance”. Their enthusiasm lay in unadorned forms of folk art, simplified language of form, ornamentation, and bold colors.

Ilya Mashkov’s “Begonias” from 1911 showed traits different from restraint and refinement – it was the image of crude but powerful centrifugal force radiated by flowers. The mighty forms and luscious colors seemed excessive, with crimson and orange flower heads pulsating vehemently against amorphous gray backgrounds.

For the Knave of Diamonds artists, “the thing and thingness as opposed to spatiality” constituted the general principle of their art, putting still life into the center of their creative activity.

Market Values: When Art Becomes Investment

The Russian art market has shown remarkable performance in still life sales. Igor Grabar’s “Pears on Red Tablecloth” became a textbook example of successful investment – more than 177% yearly growth and nearly $1 million increase over 4.5 years. The painting sold for 620,000 Danish kroner ($121,000) in December 2007 and reached $1,099,714 in June 2012.

Nicolai Fechin’s “Still Life with Fruit” from 1923 increased from $320,000 to $1,099,714, representing 47.3% yearly growth over 5.15 years. The work was painted during a rare period when Fechin was experimenting with still life – not his usual portraits that brought international fame.

According to market statistics, Russian art sales at auctions in Russia reached $9.9 million in 2019, with still life works commanding significant portions of this total. Christie’s achieved a 78% sell-through rate for Russian art sales in 2016, the highest among all auction houses.

The Soviet Challenge: Conformity vs. Creativity

During the Soviet period, still life faced unique challenges. The 1930s-40s saw development of the still life come to a halt, but since the mid-1950s the genre experienced a new rise in Soviet painting. Since that time, it finally stood firmly on par with other genres.

Soviet Nonconformist Art emerged in the 1950s as defiance against Socialist Realism constraints. Artists like Ernst Neizvestny and Vladimir Yankilevsky introduced abstraction, surrealism, and personal themes into their work. Their creations often addressed existential struggles and human condition complexities, offering stark contrast to state-sanctioned propagandistic art.

The Moscow underground scene of the 1960s became a crucible for Soviet Nonconformist Art, offering clandestine space for creativity and resistance. Artists gathered in private apartments and studios to share works, ideas, and visions. The “Bulldozer Exhibition” of 1974 became a defining moment when artists like Oskar Rabin exhibited works in defiance of Soviet censorship.

Symbolism and Hidden Meanings: More Than Pretty Objects

Russian still life painting developed its own symbolic language distinct from Western traditions. The genre became a vehicle for expressing anxieties about Russia’s destinies, attempting to unriddle secret signs of fate. Symbolism used different styles, including Impressionism, with the impressionist element of light and air being especially suitable for representing volatile and mysterious reality.

Objects in Russian still life often carried deeper meanings than their Western counterparts. Fallen leaves in compositions connoted notions of memento mori, reminding viewers of life’s transience. The careful rendering of reflections in glass and water demonstrated artists’ close observation of light distortion and refraction.

Contemporary artist Olga Rudakova (1951-2017) exemplified this approach. Her still life language was based on delicately designed plastic foundations, with intersections of pictorial symbols and universal meanings. For her, still life became a comprehensive genre – a genre-картина, genre-мироздание, genre-симфония that included landscape elements, self-portrait hints, and allegorical conflicts of life-being.

Contemporary Russian Still Life: Old Traditions, New Visions

Today’s Russian still life artists continue building on their rich heritage while incorporating modern sensibilities. Nikolai Blokhin ranks among contemporary painters who will “no doubt rank among the world’s great painters”. While known primarily for portraits, he also creates still lifes and genre paintings.

Dmitri Annenkov creates hyperrealist still lifes that make viewers “want to reach out your hand and touch, or take right from the canvas, whatever they depict”. His works are described as “just that real and alive”.

Sergey Zhavoronkov represents another approach – a minimalist who captures diversity of simple things, raising them to standard level. Having consciously chosen drawing over painting early in his career, he usually uses pastel, charcoal, and other restrained techniques. His contemplative attitude makes his favorite artists Borisov-Musatov, Bonnard, and Morandi.

The annoying thing about contemporary Russian still life is how it often gets overshadowed by more flashy contemporary art movements. But artists like Alexander Russ prove the genre’s continued relevance through his chamber, “quiet,” contemplative paintings. His constant theme involves city skylines and architectural imagery from an almost utopian harmony where walls, pipes, repair trailers, and stray dogs exist without corruption or destruction.

Technical Innovation: The Science Behind Russian Arrangements

Russian still life artists developed distinctive technical approaches that set their work apart. Petrov-Vodkin’s spherical perspective challenged traditional linear perspective by introducing multiple vanishing points and working against foreshortening rules. The three-dimensionality of objects was achieved by capturing reflections and light refraction through crystal and glass.

Igor Grabar’s divisionist technique bordered on pointillism while maintaining realistic representation. His handling of different textures – from the transparency of crystal to the heaviness of fabric – demonstrated masterful technical skill. The use of traditional Dutch blue and white china in his compositions drew parallels with 17th-century Dutch still lifes while embracing modern Impressionist trends.

Contemporary techniques continue evolving. Stanislav Plutenko combines tempera, acrylic, watercolor, and thin glazes applied by airbrush. This unique approach has earned him recognition among the top 1000 surrealists of all time.

The Global Impact: How Russian Still Life Influenced World Art

Russian still life painting’s impact extended far beyond national borders. The revolutionary approaches developed by artists like Petrov-Vodkin and the Knave of Diamonds group influenced abstract art development worldwide. The Jack of Diamonds finally disbanded in 1917 – the same year as the Russian Revolution – but their legacy profoundly shaped global abstract art development.

The market performance reflects this international recognition. Chagall became the “driver” of Russian art market globally, with 346 works sold out of 486 exhibited bringing almost $70 million in 2019. Individual transactions became exemplary investment examples, such as a self-portrait bought at Sotheby’s for $1,100,000 in 2000 and resold at Christie’s for $1,935,000 in 2019.

Quick Takeaways

Russian still life evolved from academic exercise to revolutionary art form that influenced global abstract development. The genre gained equality with portraits and historical painting through technical innovation and symbolic depth. Market performance demonstrates continued collector interest, with record-breaking sales like Petrov-Vodkin’s £9.3 million “Still Life with Lilac.” Soviet period created unique underground scenes that preserved artistic freedom through clandestine exhibitions. Contemporary artists balance traditional techniques with modern approaches, maintaining the genre’s relevance. Russian still life’s symbolic language differs from Western traditions through deeper philosophical meanings. The spherical perspective technique revolutionized spatial representation in art.

The Continuing Legacy

Russian still life painting represents more than artistic tradition – it embodies a nation’s struggle with tradition versus innovation, conformity versus creative freedom. From Khrutsky’s first academic exercises to Petrov-Vodkin’s revolutionary perspectives, from the Knave of Diamonds’ rebellious exhibitions to today’s hyperrealist masterpieces, the genre continues evolving.

I learned this when researching auction records – the prices tell stories of artistic recognition that goes far beyond mere decoration. These works capture moments in cultural history when artists risked everything to express individual vision against overwhelming pressure to conform.

The Russian approach to still life arrangement and meaning offers lessons for contemporary artists worldwide. Whether working in traditional or experimental styles, the emphasis on symbolic content, technical innovation, and philosophical depth creates art that transcends mere representation. In a world increasingly dominated by digital imagery, the careful observation and patient craft required for still life painting becomes even more precious.

The genre’s future looks bright, with new generations of Russian artists continuing to push boundaries while honoring their rich heritage. As global art markets increasingly recognize Russian contributions, still life painting from this tradition will undoubtedly continue commanding attention and investment. The combination of technical excellence, symbolic depth, and revolutionary spirit ensures Russian still life remains relevant and influential for generations to come.

FAQs

What makes Russian still life different from other traditions?

Russian still life incorporates deeper philosophical meanings and symbolic content compared to Western traditions. Artists like Petrov-Vodkin developed unique techniques such as spherical perspective, while the Knave of Diamonds group combined European modernism with Russian folk art elements. The genre also served as vehicle for political and social commentary, especially during Soviet period when artists used subtle symbolism to express restricted ideas.

Why are Russian still life paintings so expensive at auction?

Russian still life works command high prices due to historical significance, technical innovation, and limited availability. Record sales like Petrov-Vodkin’s £9.3 million “Still Life with Lilac” reflect growing international recognition of Russian contributions to modern art. Market statistics show 78% sell-through rates for Russian art at major auction houses, with many works appreciating over 100% annually.

How did Soviet politics affect still life painting?

Soviet politics created unique challenges and opportunities for still life artists. Official Socialist Realism restricted artistic freedom, leading to underground movements where still life became vehicle for subtle resistance. Artists developed coded symbolic languages to express forbidden ideas through arrangement of everyday objects. The genre experienced renaissance during the 1950s thaw period.

What techniques are unique to Russian still life artists?

Russian still life artists developed several distinctive techniques including Petrov-Vodkin’s spherical perspective, Grabar’s divisionist approach bordering on pointillism, and the Knave of Diamonds’ combination of European modernism with folk art elements. Contemporary artists like Plutenko use unique combinations of tempera, acrylic, watercolor, and airbrush techniques to create unprecedented effects.

Which Russian still life artists should collectors watch today?

Contemporary collectors should watch Nikolai Blokhin for masterful technique across genres, Dmitri Annenkov for hyperrealist approaches, and Sergey Zhavoronkov for minimalist contemplative works. These artists continue building on Russian traditions while developing personal innovations that attract international attention and investment.