The Russian Avant-Garde stands as one of the most transformative artistic movements of the 20th century. Between 1890 and 1930, Russian artists dismantled centuries of tradition, creating bold new visual languages that would reshape modern art worldwide. From Kazimir Malevich’s radical Black Square to Vladimir Tatlin’s visionary tower, these artists didn’t just make art. They reimagined what art could be.

Quick Answer

The Russian Avant-Garde was a groundbreaking artistic movement that flourished from approximately 1890 to 1930 in Russia and the early Soviet Union. Characterized by radical experimentation in abstraction, geometry, and industrial materials, it encompassed multiple styles including Suprematism, Constructivism, and Cubo-Futurism. These artists sought to create a new visual language that reflected the revolutionary changes sweeping through Russian society, producing works that would profoundly influence 20th-century modern art worldwide.

What is the Russian Avant-Garde?

The Russian Avant-Garde refers to a powerful wave of artistic innovation that emerged in the Russian Empire and flourished through the early Soviet period. This movement brought together diverse experimental styles, each pushing the boundaries of visual expression in distinct ways. Artists working within this framework rejected traditional representational art, instead exploring pure geometric forms, bold color relationships, and the integration of art with everyday life.

The movement encompassed several interconnected schools of thought. Suprematism, pioneered by Kazimir Malevich, reduced painting to its essential elements of shape and color. Constructivism, led by Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko, sought to merge art with industrial design and social utility. Meanwhile, movements like Cubo-Futurism, Rayonism, and Neo-Primitivism bridged European modernism with distinctly Russian artistic traditions.

What united these varied approaches was a shared conviction that art must reflect and shape the modern world. The Russian Avant-Garde artists saw themselves not merely as creators of beautiful objects but as architects of a new visual and social reality.

![Kazimir Malevich, Black Square (c. 1915), Oil on linen, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow]](https://rus-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Kazimir_Malevich_1915_Black_Suprematic_Square-1024x1024.jpg)

From Imperial Russia to Revolutionary Vision

The roots of the Russian Avant-Garde stretch back to the final decades of the 19th century, when Russian artists began absorbing European modernist influences. The opening of major private collections in Moscow, particularly those of Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, exposed Russian artists to works by Picasso, Matisse, Gauguin, and Cézanne. These collections contained more than 200 French Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and Cubist works, providing Russian artists with direct access to cutting-edge Western art.

However, Russian artists didn’t simply imitate their European counterparts. They synthesized Western innovations with indigenous traditions, including Russian Orthodox icons and folk art known as lubok. This fusion created something entirely new. Artists like Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov founded movements such as Neo-Primitivism, which deliberately incorporated elements from Russian folk culture alongside modernist techniques.

The years leading up to the 1917 Russian Revolution saw explosive creativity. In 1913, the Futurist opera Victory over the Sun premiered in Saint Petersburg, featuring sets and costumes by Malevich that included the first appearance of a black square. This period witnessed fierce debates, provocative exhibitions, and radical manifestos as artists competed to define the future of art.

The Revolutionary Breakthrough of 1915

December 1915 marked a pivotal moment in art history. At The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 in Petrograd, Kazimir Malevich unveiled 39 abstract works, including his Black Square. He positioned this painting high in the corner of the room, the traditional placement for Orthodox icons in Russian homes. This deliberate choice signaled that Suprematism would serve as a new form of spiritual expression for the modern age.

The painting itself appears deceptively simple: a black quadrilateral on a white field. Yet Malevich considered it the zero point of painting, the foundation upon which an entirely new art could be built. In his manifesto, he declared that Suprematism would free art from the burden of representing the objective world, focusing instead on pure feeling conveyed through geometric relationships.

The exhibition sparked intense controversy. Malevich and his rival Vladimir Tatlin quarreled publicly over their competing visions. While Malevich pursued non-objective painting, Tatlin developed three-dimensional constructions he called counter-reliefs, works that would lay the groundwork for Constructivism.

Key Characteristics That Defined the Movement

Several distinctive features set the Russian Avant-Garde apart from contemporary European movements. First, these artists embraced geometric abstraction with unprecedented rigor. Unlike the organic abstractions of Wassily Kandinsky, Suprematist works employed circles, squares, triangles, and lines arranged according to principles of dynamic balance rather than representational logic.

Second, the movement showed a pronounced interest in modern materials and industrial processes. Constructivists celebrated steel, glass, and concrete as symbols of the machine age. Artists like Tatlin and Rodchenko explored the inherent properties of materials rather than treating them as mere vehicles for artistic expression.

Third, Russian Avant-Garde artists developed a unique relationship between art and politics. Following the 1917 Revolution, many artists saw their experimental work as aligned with revolutionary social change. They believed their new visual languages could help build a new Soviet society, leading them to design everything from propaganda posters to workers’ clothing to architectural projects.

Fourth, the movement displayed remarkable cross-disciplinary ambition. Avant-Garde artists designed theater sets, created innovative typography, made experimental films, and developed new approaches to photography. This holistic vision sought to transform all aspects of visual culture simultaneously.

Major Figures Who Shaped the Movement

Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935) founded Suprematism and created some of the first truly abstract paintings in art history. Born near Kiev, Malevich studied various European styles before developing his distinctive geometric approach. His later works, including White on White (1918), took abstraction to even more radical extremes. Despite persecution under Stalin, Malevich’s influence on modern art proved immeasurable.

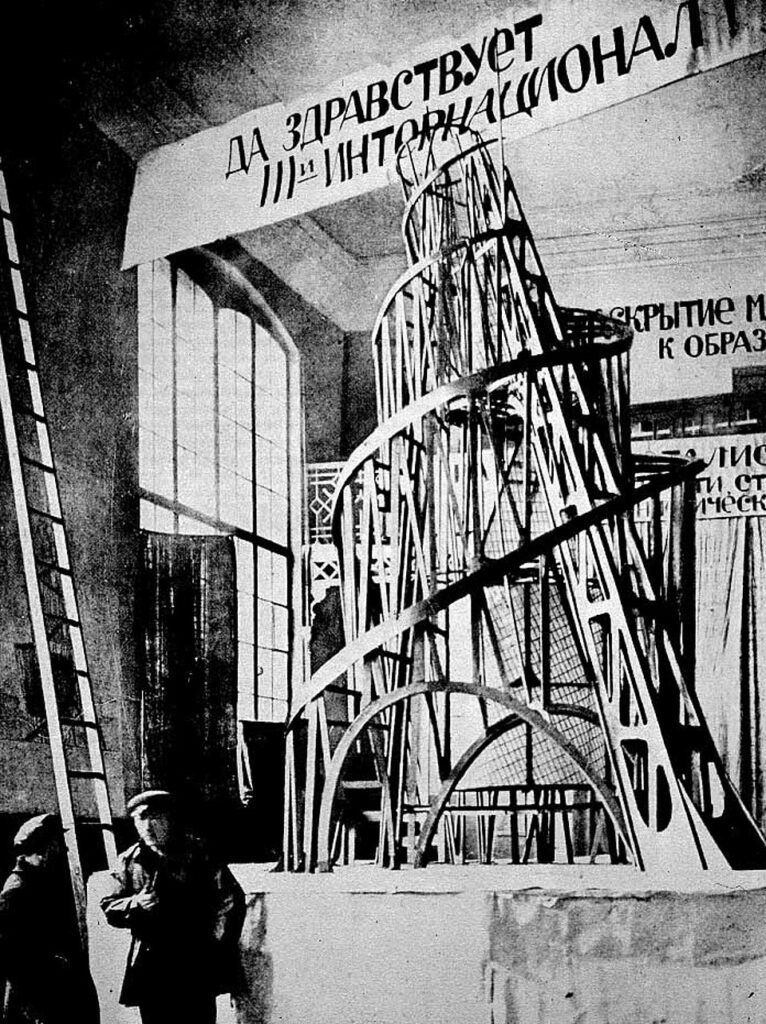

Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953) pioneered Constructivism with his counter-reliefs and his visionary Monument to the Third International, commonly known as Tatlin’s Tower. This unrealized architectural design, conceived in 1919, would have stood 400 meters tall, surpassing the Eiffel Tower. Its spiraling iron and glass structure embodied the fusion of art, engineering, and revolutionary politics that defined Constructivist ideals.

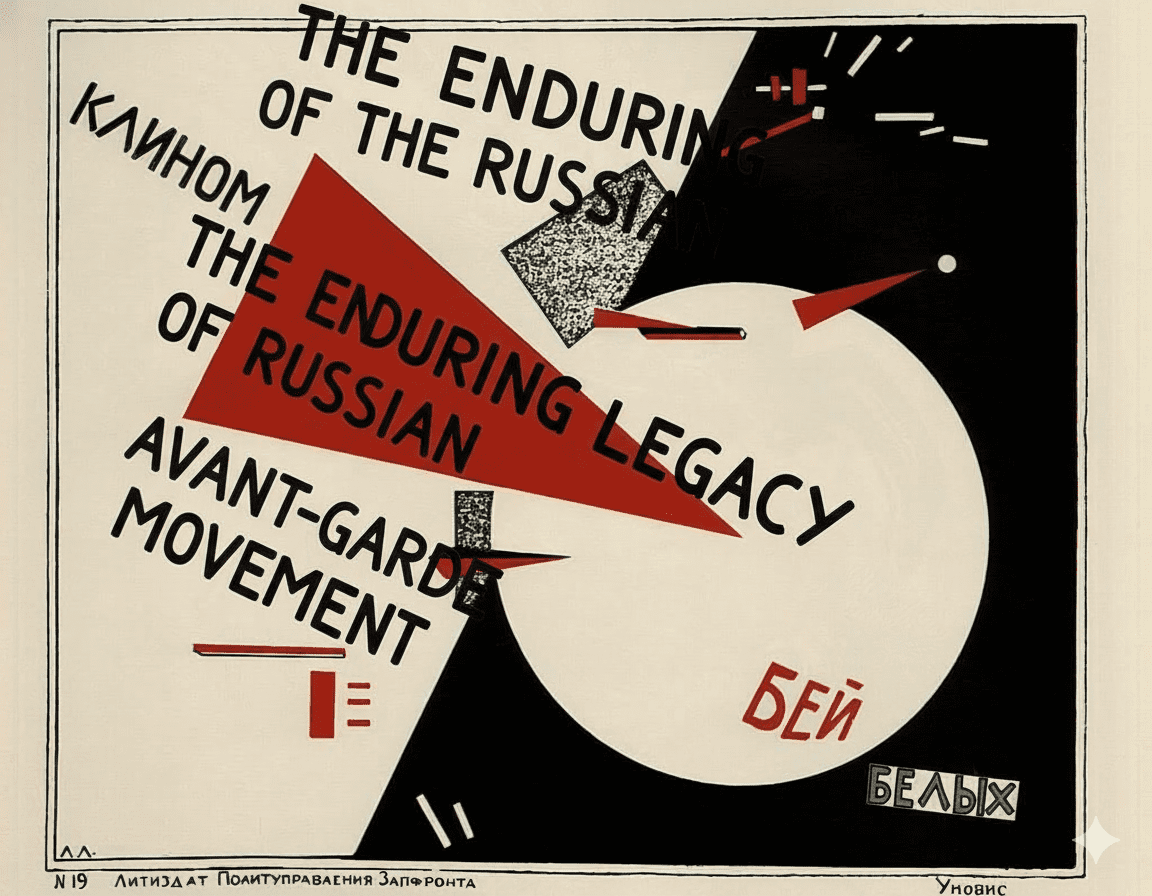

El Lissitzky (1890-1941) served as a crucial bridge between Russian and Western European avant-gardes. His Proun series explored three-dimensional geometric compositions, while his innovative graphic design and typographic work influenced the Bauhaus movement in Germany. Lissitzky’s skills as both artist and theorist made him one of the movement’s most effective international ambassadors.

Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956) excelled across multiple media. His photography, graphic design, and photomontage techniques established new standards for visual communication. Rodchenko embraced the Constructivist principle of “production art,” creating functional designs for books, posters, and everyday objects that served the needs of Soviet society.

Lyubov Popova (1889-1924) brought extraordinary dynamism to Constructivist painting. Her Painterly Architectonics series demonstrated how geometric forms could convey movement and energy. She also designed striking textiles and theater sets, exemplifying the Constructivist goal of merging fine art with industrial production.

Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962) and Mikhail Larionov (1881-1964) founded Neo-Primitivism and Rayonism, movements that incorporated Russian folk art traditions while exploring abstraction. Their bold colors and dynamic compositions influenced many younger avant-garde artists.

💰 Did You Know?

When Kazimir Malevich died in 1935, his funeral procession was a Suprematist spectacle. His coffin, designed in a Suprematist style, was transported in a vehicle bearing a large Black Square on its front. Mourners carried flags decorated with black squares, and his grave was originally marked with a cube featuring the iconic square, creating a final artistic statement that merged life, death, and pure geometric form.

Notable Works That Changed Art History

Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915) represents perhaps the most influential single work of the Russian Avant-Garde. This painting eliminated every trace of the natural world, presenting instead a pure geometric form. Malevich painted four versions between 1915 and the early 1930s, now housed in major Russian museums including the State Tretyakov Gallery and the State Hermitage Museum.

Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (1919-1920) exists only as a model, yet its impact exceeded that of many realized buildings. The design featured a leaning double helix framework enclosing rotating glass volumes (a cube, pyramid, and cylinder). These structures would complete rotations at different intervals: annually, monthly, and daily. The monument embodied the Constructivist dream of uniting art, technology, and revolutionary politics in a single structure.

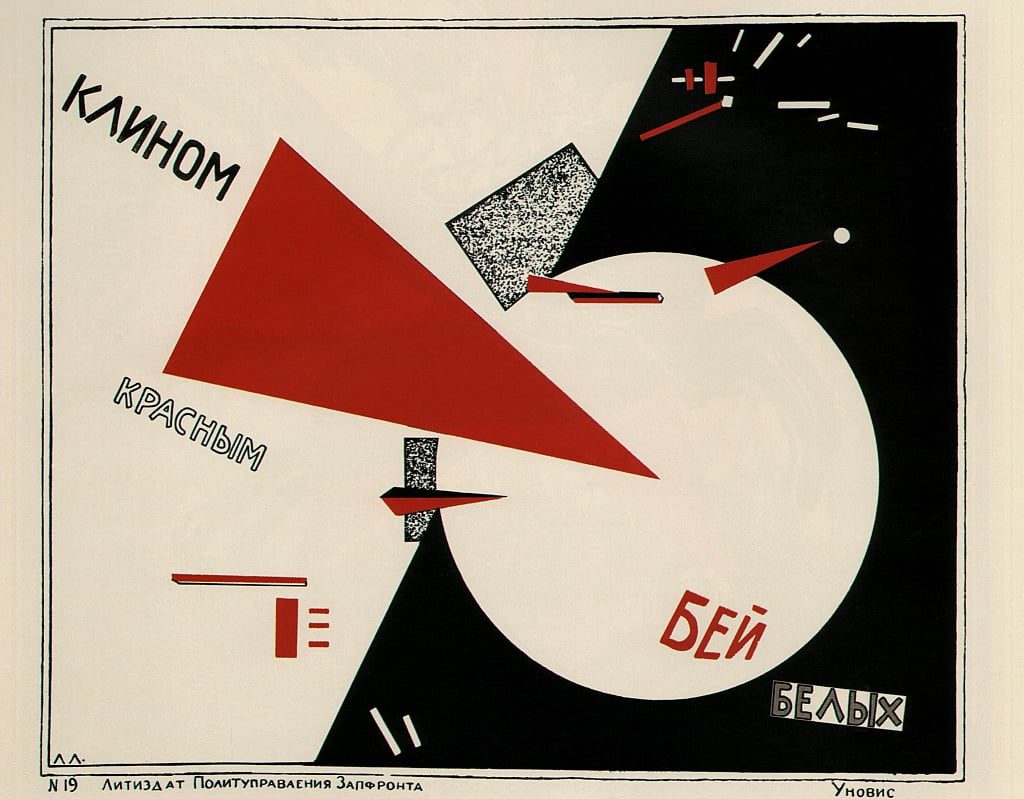

El Lissitzky’s Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919) transformed Suprematist abstraction into effective political communication. This lithographic poster used simple geometric shapes (a red triangle piercing a white circle) to symbolize the Bolshevik victory in the Russian Civil War.

Alexander Rodchenko’s series of Black Paintings (1918) consisted of canvases painted in single colors (black, red, yellow). These works paralleled Malevich’s White on White, representing another endpoint of painting’s evolution. Rodchenko subsequently abandoned painting for photography and design, declaring that painting had reached its logical conclusion.

Wassily Kandinsky’s Compositions from the 1910s, while created partly outside Russia, profoundly influenced the Russian scene. His theoretical writings, particularly Concerning the Spiritual in Art, provided philosophical justification for abstract art that resonated throughout the avant-garde community.

The Revolutionary Period and Utopian Dreams

The October Revolution of 1917 initially energized the avant-garde. Many artists believed the political revolution would create space for their artistic innovations. The new Soviet government commissioned avant-garde artists to design revolutionary festivals, propaganda posters, and public monuments. Lunacharsky, the People’s Commissar of Education, supported experimental art and protected avant-garde institutions.

Between 1918 and the mid-1920s, Russian Avant-Garde artists enjoyed unprecedented opportunities to implement their ideas. VKHUTEMAS (Higher Art and Technical Studios), established in 1920, became a laboratory for avant-garde pedagogy, combining fine art education with industrial design training. Artists like Rodchenko, Popova, and Tatlin taught there, training a new generation in Constructivist principles.

The avant-garde also transformed public space through street decorations for revolutionary holidays, innovative theater productions, and experimental film. Directors like Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov applied Constructivist principles to cinema, creating montage techniques that influenced filmmaking worldwide.

This period saw the creation of ambitious architectural projects. Ivan Leonidov, Konstantin Melnikov, and other Constructivist architects designed workers’ clubs, communal housing, and public buildings that embodied socialist ideals through geometric forms and functional planning.

How Socialist Realism Ended the Experiment

By the late 1920s, the Soviet government’s attitude toward experimental art began shifting. Joseph Stalin’s consolidation of power brought increasing emphasis on art that ordinary workers could immediately understand and appreciate. The avant-garde’s abstract explorations seemed elitist and disconnected from proletarian experience.

In 1932, the Central Committee issued a decree restructuring all literary and artistic organizations. This effectively ended the pluralistic artistic culture of the 1920s. Socialist Realism was declared the sole acceptable style, demanding that art be realistic, optimistic, accessible, and supportive of socialist construction.

For avant-garde artists, this shift proved devastating. Some, like Malevich, returned to figurative painting, creating works that showed peasants and workers in traditional styles. Others, including El Lissitzky, redirected their talents toward propaganda and exhibition design within Socialist Realist frameworks. Still others found their work suppressed, hidden in museum storage, or destroyed.

The suppression was thorough. Between the mid-1930s and the 1980s, major Russian Avant-Garde works remained largely invisible to Soviet audiences. The State Tretyakov Gallery stored masterpieces like Malevich’s Black Square in its reserves, away from public view. Only during glasnost did these works reemerge for widespread exhibition.

The Movement’s Impact on International Modernism

Despite suppression within the Soviet Union, the Russian Avant-Garde exerted profound influence internationally. El Lissitzky’s travels and exhibitions spread Constructivist ideas throughout Europe, directly influencing the Bauhaus school in Germany and the De Stijl movement in the Netherlands.

The principles of Suprematism and Constructivism shaped the development of geometric abstraction in Western art. American artists including Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, and the Minimalists of the 1960s acknowledged their debt to Russian precedents. Donald Judd and Carl Andre’s sculptural works directly descended from Tatlin’s and Rodchenko’s three-dimensional constructions.

Modern graphic design owes enormous debts to Russian Avant-Garde typography and photomontage. The bold asymmetrical layouts, sans-serif typefaces, and integration of photography with text that Rodchenko, Lissitzky, and others pioneered became standard tools of 20th-century visual communication. Contemporary graphic designers continue to reference these innovations.

In architecture, the influence proved equally significant. Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and other pioneers of modern architecture studied Russian Constructivist projects. The International Style that dominated mid-century architecture incorporated lessons from Constructivist emphasis on function, geometric forms, and industrial materials.

Preserving and Rediscovering the Legacy

The story of the Russian Avant-Garde’s rediscovery represents a fascinating chapter in art history. During the Cold War, Western museums and scholars gradually pieced together knowledge of these suppressed works. Alfred Barr, founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, smuggled works by Malevich out of Nazi Germany in 1935, providing crucial evidence of the movement’s achievements.

Collector George Costakis assembled the most comprehensive private collection of Russian Avant-Garde art during the Soviet period, acquiring works that had been hidden, forgotten, or deemed worthless under Stalin. Before leaving the Soviet Union in 1977, Costakis donated more than 800 works to the State Tretyakov Gallery, including 142 paintings and 692 graphic works. This donation significantly strengthened the museum’s avant-garde holdings.

Today, the New Tretyakov Gallery at Krymsky Val houses Russia’s most comprehensive public exhibition of 20th-century art, including extensive avant-garde collections. Visitors can see masterpieces by Malevich, Kandinsky, Popova, Rodchenko, and others that were hidden for decades. The State Tretyakov Gallery continues to conduct research, restoration, and exhibitions focused on this crucial period.

International institutions have mounted major retrospectives. The Museum of Modern Art in New York organized significant exhibitions examining the movement’s innovations in painting, design, film, and architecture. Tate Modern in London has similarly showcased Russian Avant-Garde works, introducing new generations to their enduring power.

Ongoing Influence in Contemporary Art and Design

The Russian Avant-Garde’s legacy extends far beyond art museums. Contemporary designers regularly reference Constructivist aesthetics in fashion, furniture, and product design. Architectural firms continue exploring the geometric languages and spatial concepts pioneered by Constructivist architects.

Digital designers and web developers frequently cite Russian Avant-Garde typography and layout principles as inspiration. The movement’s bold use of geometric shapes, limited color palettes, and integration of text with images translates remarkably well to screen-based media.

Contemporary artists continue engaging with avant-garde concepts. Some create works in direct dialogue with historical pieces, while others adapt avant-garde principles to address current social and political concerns. The movement’s conviction that art can actively shape society rather than merely reflect it resonates with socially engaged artists today.

Even popular culture shows avant-garde influence. Music videos, album covers, and advertising campaigns frequently borrow the movement’s visual vocabulary. Film directors reference Constructivist montage techniques and geometric compositions. The aesthetic has become so widely disseminated that many people encounter it without recognizing its Russian origins.

Common Misconceptions About the Movement

Many people assume the Russian Avant-Garde was uniformly Communist in its politics. While some artists enthusiastically supported the Bolshevik Revolution, others maintained more complex or ambivalent relationships with Soviet power. Before 1917, most avant-garde artists were essentially apolitical, concerned primarily with aesthetic innovation rather than political ideology.

Another misconception holds that abstract art inevitably led to political radicalism. In fact, the relationship between artistic and political revolution proved more complicated. The Soviet government ultimately rejected abstract art despite its revolutionary origins, preferring representational Socialist Realism that more directly communicated political messages.

Some viewers mistakenly believe Russian Avant-Garde art requires no skill or effort to create. The apparent simplicity of works like Black Square obscures the intense theoretical work, technical experimentation, and conceptual rigor behind them. Malevich spent months in his studio developing Suprematism, creating numerous complex compositions before arriving at the radical reduction of the black square.

People sometimes conflate the Russian Avant-Garde with Russian Futurism, treating them as identical. While significant overlap existed, Russian Futurism specifically referred to poetry and literature that employed innovative language experiments, though visual artists certainly participated in Futurist activities. The visual arts avant-garde encompassed broader movements including Suprematism and Constructivism.

Finally, many assume the movement ended completely with Stalin’s cultural crackdown. While official support vanished and major artists either adapted or fell silent, avant-garde ideas persisted underground and influenced later generations of non-conformist Soviet artists. The conceptual art that emerged in the 1960s drew on avant-garde precedents.

Related Movements and Artistic Connections

The Russian Avant-Garde developed in constant dialogue with Western European modernism. Italian Futurism, with its celebration of speed, technology, and dynamism, significantly influenced Russian artists. Filippo Marinetti visited Russia in 1914, though Russian artists ultimately rejected what they saw as Futurism’s excessive glorification of war and destruction.

Cubism provided crucial formal lessons. Russian artists studied Picasso’s and Braque’s fractured perspectives and geometric simplifications, then pushed these techniques toward complete abstraction. The term Cubo-Futurism reflects this synthesis of Cubist formal analysis with Futurist energy.

German Expressionism shared the avant-garde’s interest in emotional intensity and anti-academic positions, though the Russians pursued more rigorous geometric abstraction. Wassily Kandinsky, though Russian-born, worked primarily in Germany and helped establish connections between the two scenes.

The Bauhaus school in Germany became perhaps the most important institutional inheritor of Russian Avant-Garde principles. When Lissitzky and other artists brought Constructivist ideas westward, figures like László Moholy-Nagy, Walter Gropius, and others integrated them into Bauhaus pedagogy, transmitting avant-garde innovations to a new international context.

Dutch De Stijl shared the Russian movements’ commitment to geometric abstraction and utopian social vision. Piet Mondrian’s grid-based compositions and Theo van Doesburg’s writings on Neo-Plasticism developed parallel to Russian experiments, though with less emphasis on industrial materials and three-dimensional construction.

Essential Points About the Russian Avant-Garde Movement

- The Russian Avant-Garde flourished between approximately 1890 and 1930, reaching its creative peak during and immediately following the 1917 Russian Revolution.

- Major sub-movements included Suprematism (founded by Kazimir Malevich), Constructivism (pioneered by Vladimir Tatlin), Neo-Primitivism, Rayonism, and Cubo-Futurism, each with distinct aesthetic principles and goals.

- Key artists such as Malevich, Tatlin, El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko, Lyubov Popova, and Wassily Kandinsky created works that fundamentally redefined the possibilities of visual art.

- The movement emphasized geometric abstraction, industrial materials, integration of art with everyday life, and a belief that artistic innovation could contribute to revolutionary social change.

- Landmark works include Malevich’s Black Square (1915), Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (1919-1920), and countless innovative designs in typography, photography, film, and architecture.

- Stalin’s rise to power and the 1932 decree establishing Socialist Realism as the sole acceptable artistic style effectively ended the avant-garde period, suppressing experimental art for decades.

- Despite suppression in the Soviet Union, the Russian Avant-Garde profoundly influenced Western modernism, including the Bauhaus, De Stijl, American Minimalism, and modern graphic design.

- Major collections reside in the State Tretyakov Gallery and State Russian Museum in Russia, as well as international institutions like MoMA in New York and Tate Modern in London, where the public can study these groundbreaking works.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Q – What makes the Russian Avant-Garde different from other modern art movements?

- A – The Russian Avant-Garde distinguished itself through its unique synthesis of radical abstraction, utopian politics, and practical application. Unlike Western European modernists who focused primarily on easel painting, Russian artists sought to integrate art into all aspects of life, from industrial design to architecture. Their work emerged from a distinctively Russian cultural context, incorporating indigenous traditions while pushing abstraction further than most European contemporaries.

- Q – Why did the Soviet government suppress the Russian Avant-Garde?

- A – Under Stalin, the Soviet government viewed abstract avant-garde art as too complex and elitist for ordinary workers to understand. In 1932, authorities decreed that all art must follow Socialist Realism, a representational style depicting idealized workers and optimistic scenes of socialist construction. The government believed this accessible, narrative art would more effectively communicate political messages than abstract geometric compositions.

- Q – What does Suprematism mean in art?

- A – Suprematism, founded by Kazimir Malevich in 1915, emphasized the supremacy of pure artistic feeling expressed through basic geometric forms and limited colors. Malevich eliminated all representational content, creating compositions from shapes like squares, circles, and rectangles. He believed this approach freed art from depicting the material world, allowing it to convey pure sensation and spiritual experience through formal relationships.

- Q – How did Kazimir Malevich influence modern art?

- A – Malevich’s Black Square and subsequent Suprematist works established geometric abstraction as a viable artistic language. His reduction of painting to essential forms influenced countless later artists, from American Minimalists like Donald Judd and Carl Andre to contemporary abstract painters. His theoretical writings provided philosophical justification for non-representational art that shaped modernist thinking throughout the 20th century.

- Q – Where can I see Russian Avant-Garde art today?

- A – The State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow houses the world’s most comprehensive collection, with its New Tretyakov building dedicated to 20th-century art including extensive avant-garde holdings. The State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg also maintains significant collections. Internationally, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Tate Modern in London, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris feature important Russian Avant-Garde works in their permanent collections.