Russian Art Through the Ages: How Portraits Shaped a Nation

Russian art has always been more than just pretty pictures hanging in galleries. For centuries, artists in Russia have been quietly – and sometimes not so quietly – building the country’s identity through their brushstrokes. From the golden icons of medieval churches to the bold propaganda posters of the Soviet era, Russian art tells the story of a nation constantly defining and redefining itself.

The thing is, most people outside Russia dont really get how deep this connection runs. Sure, everyone knows about those colorful onion domes and maybe they’ve seen a Kandinsky in a museum somewhere. But the real story? That’s buried in portrait galleries and dusty archives, waiting for someone to piece it together.

When you look at Russian art – I mean really look at it – you start to see patterns. You see how artists weren’t just making art for art’s sake. They were making statements, taking sides, and quite literally painting the face of Russian identity onto canvas. Sometimes that meant glorifying the Tsars, sometimes it meant capturing the suffering of peasants, and sometimes it meant reimagining what it even meant to be Russian.

This isn’t your typical art history lesson. We’re going to dig into how Russian art became a battleground for ideas about national identity, and how those battles are still being fought today.

The Icons That Started It All

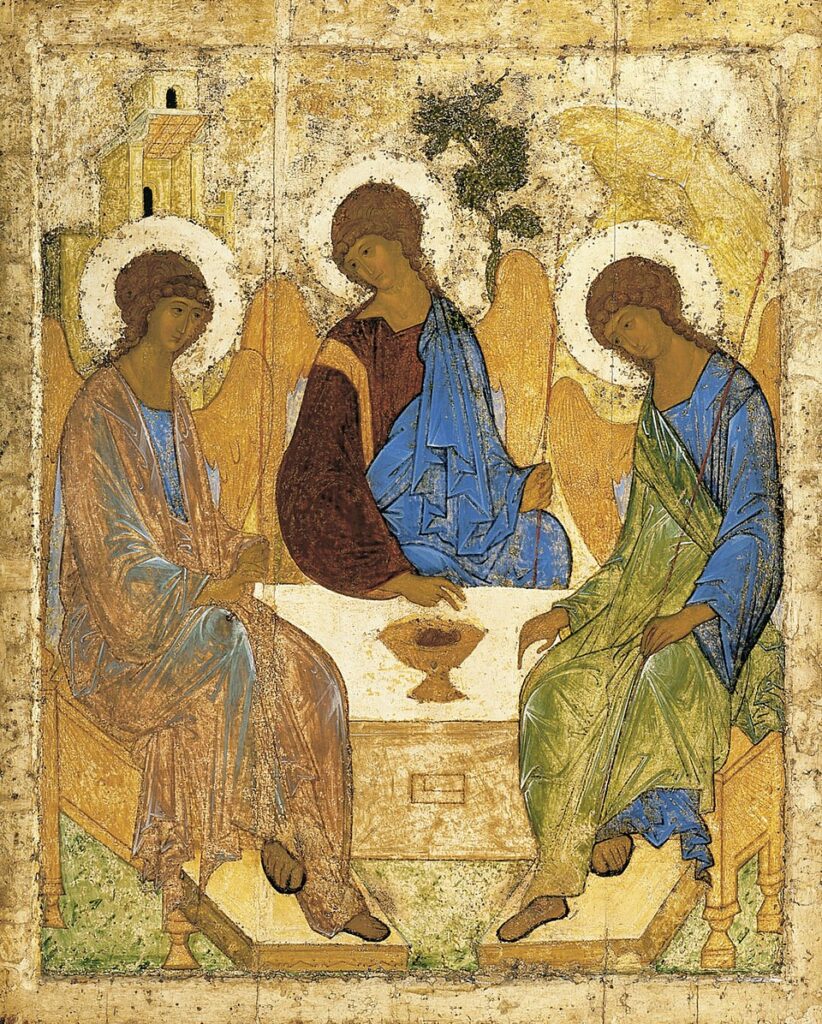

Before Russia had a national art scene, it had icons. These weren’t just religious paintings – they were the foundation stones of Russian visual culture. When Prince Vladimir converted to Christianity in 988, he didn’t just change the country’s religion; he set off an artistic revolution that would echo for centuries.

Icon painting came to Russia from Byzantium, but something interesting happened when it crossed the border. Russian artists took those Byzantine formulas and slowly, carefully, made them their own. The faces got softer, the colors got warmer, and somehow the whole thing became distinctly Russian.

Take Andrei Rublev’s “Trinity” from around 1425. This isn’t just any religious painting – its considered one of the masterpieces of world art. But more than that, it’s one of the first times you can see a uniquely Russian sensibility emerging. The gentle, contemplative faces, the harmony of the composition – this is Russian art finding its voice.

The annoying thing about studying early Russian art is that so much of it has been lost or destroyed over the centuries. Wars, fires, and political upheavals have taken their toll. But what survived tells an incredible story of artists who were simultaneously serving God, serving their rulers, and serving some deeper vision of what Russian culture could become.

By the 16th century, icon painting was evolving into something called “parsuna” – a hybrid between traditional icons and Western-style portraits. This might seem like a small technical shift, but it was actually huge. For the first time, Russian artists were depicting real, contemporary people using techniques that emphasized their individuality rather than their spiritual significance.

Portraits and Power Under the Tsars

When Peter the Great opened Russia’s windows to the West in the early 18th century, art became a battlefield. The old Byzantine traditions clashed with new European influences, and artists found themselves caught in the middle. But here’s what’s fascinating – instead of just copying Western styles, the best Russian artists used these new techniques to explore what made Russia unique.

The Academy of Arts, founded in St. Petersburg in 1757, became the epicenter of this cultural transformation. Think of it as Russia’s art boot camp, where talented young painters learned to master European techniques while grappling with distinctly Russian themes. The Academy produced generations of artists who could paint like their European contemporaries but saw the world through Russian eyes.

Portrait painting became particularly important during this period. When you’re trying to build a modern empire, you need images that project power and legitimacy. Russian portrait painters became incredibly skilled at this game. They could make a merchant look like nobility, a general look heroic, and a Tsar look divine.

But the really interesting stuff happened when these artists turned their attention to Russian society itself. Painters like Alexey Antropov and Ivan Argunov started creating portraits that weren’t just about individual people – they were about types, about the different kinds of people who made up Russian society. A noble in European dress here, a merchant in traditional costume there, a peasant woman with weathered hands and knowing eyes.

These portraits were doing something unprecedented – they were creating a visual inventory of Russian identity. For the first time, you could look at a collection of paintings and see Russia as a complex, multi-layered society rather than just a feudal hierarchy topped by a distant Tsar.

The Realist Revolution

Everything changed in the 1860s. Russia was going through massive social upheavals – the emancipation of the serfs, rapid industrialization, growing political tensions. Artists couldn’t just keep painting pretty portraits of nobles anymore. The country was demanding art that engaged with reality.

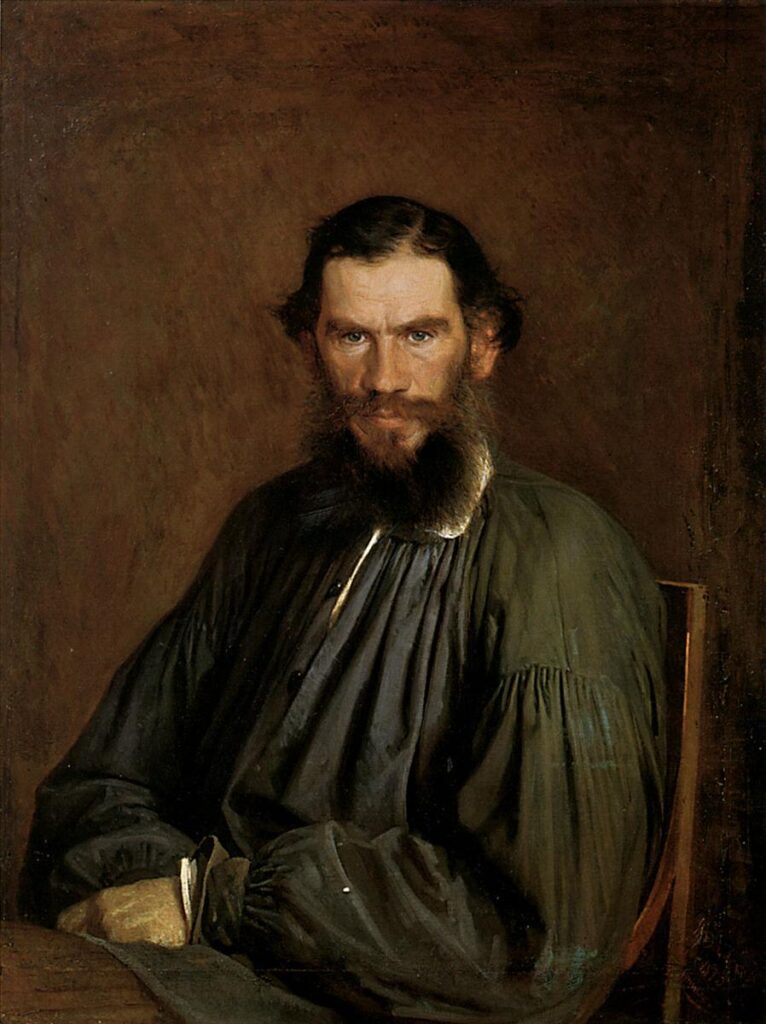

Enter the Wanderers, or “Peredvizhniki” as they were known in Russian. These artists basically said “screw the Academy and its classical subjects” and took their art directly to the people. They organized traveling exhibitions that brought contemporary Russian art to cities and towns across the empire. It was revolutionary, and it worked.

The Wanderers included some of the greatest names in Russian art – Ilya Repin, Ivan Shishkin, Vasily Surikov. These weren’t just talented painters; they were cultural warriors who believed art should engage with social issues. Repin’s “Barge Haulers on the Volga” didn’t just show some guys pulling a boat – it was a searing indictment of social inequality. Surikov’s historical paintings weren’t just depicting past events – they were asking hard questions about power, resistance, and Russian identity.

What made the Wanderers special was their commitment to showing all of Russia, not just the privileged classes. Peasants, workers, merchants, intellectuals – everyone got their portrait painted, and everyone was treated with dignity. For the first time in Russian art, ordinary people weren’t just background figures or symbols – they were the heroes of their own stories.

The Wanderers also pioneered landscape painting as a form of national expression. When Ivan Shishkin painted a Russian forest, he wasn’t just making a pretty picture – he was arguing that Russian nature was worth celebrating, that there was something unique and valuable about the Russian landscape. This might sound obvious now, but at the time it was radical.

Art Collectors as Nation Builders

Pavel Tretyakov changed everything. This Moscow textile merchant started collecting Russian art in the 1850s with a crazy goal – he wanted to create a complete portrait gallery of Russian cultural achievement. By the time he donated his collection to the city of Moscow in 1892, he had assembled one of the most important art collections in the world.

But Tretyakov wasn’t just buying art – he was actively commissioning it. He would approach artists and ask them to paint portraits of important Russian writers, composers, and thinkers. He wanted to create a visual pantheon of Russian genius, and he largely succeeded. Walking through the Tretyakov Gallery today is like attending a reunion of 19th-century Russian culture.

The impact of collectors like Tretyakov can’t be overstated. They created a market for Russian art, gave artists financial independence, and most importantly, they created institutions where Russian identity could be explored and celebrated. When ordinary Russians visited these galleries, they weren’t just looking at paintings – they were encountering themselves as a people with a rich cultural heritage.

Other collectors followed Tretyakov’s lead. The Morozov brothers built incredible collections of both Russian and European art. Sergei Shchukin became one of the world’s great collectors of French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art, but he also supported Russian artists who were experimenting with modern styles.

These collections became laboratories where Russian artists could study global trends while working out their own artistic responses. The result was an explosion of creativity that produced some of the most innovative art in the world.

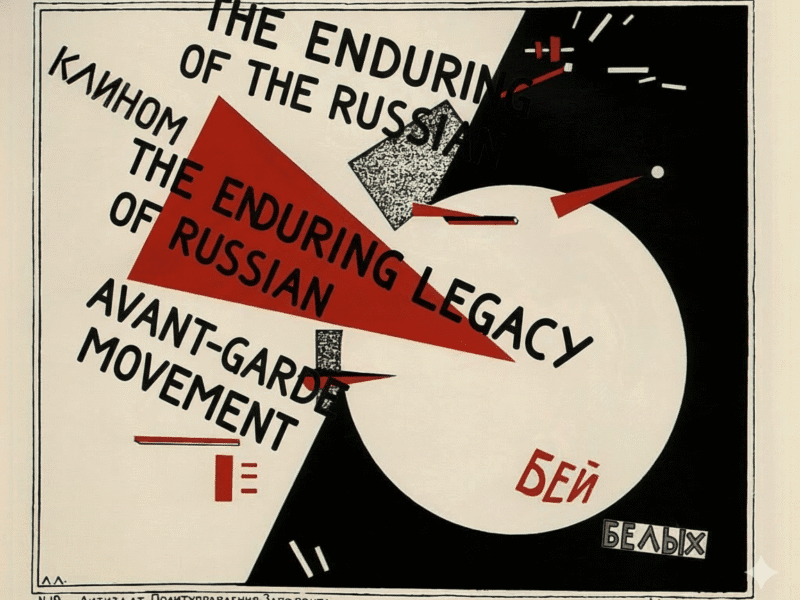

The Avant-Garde Explosion

Just when Russian art seemed to be settling into comfortable realism, everything exploded. The early 20th century brought an artistic revolution that was so radical, so innovative, that its effects are still being felt today. Russian artists didn’t just participate in the international avant-garde movement – they led it.

Wassily Kandinsky basically invented abstract art. Kasimir Malevich painted a black square on a white background and called it the future. Marc Chagall created dreamlike images that combined Russian folk culture with modernist techniques. These weren’t just art experiments – they were attempts to create entirely new visual languages for the modern world.

But here’s what’s really interesting – even the most radical Russian avant-garde artists were still deeply engaged with Russian identity. Kandinsky’s abstractions were inspired by Russian folk art and spiritual traditions. Malevich’s suprematist paintings were attempts to create a pure Russian art freed from Western influences. Chagall’s surreal compositions were populated with characters from Russian-Jewish village life.

The avant-garde movement also produced some of the most powerful political art of the 20th century. Artists like Alexander Rodchenko and Gustav Klutsis created propaganda posters that were simultaneously works of art and political statements. They believed that revolutionary art should help create a revolutionary society.

This period was incredibly fertile but also incredibly brief. By the 1930s, Stalin’s regime was cracking down on artistic experimentation, and many of the greatest avant-garde artists were forced into exile or silence.

Soviet Portraits of Progress

Soviet art gets a bad reputation, and alot of it is deserved. The official style of Socialist Realism produced mountains of propaganda that was more concerned with ideology than artistic merit. But dismissing all Soviet art as propaganda is a mistake – some genuinely great work was produced, and even the propaganda tells us important things about how the Soviet state tried to shape Russian identity.

The official portraits of Soviet leaders are fascinating documents. They show how the regime wanted to be seen – Stalin as the wise father of the nation, Lenin as the visionary leader, Brezhnev as the steady hand guiding progress. These weren’t just political documents; they were attempts to create new models of Russian leadership.

But the really interesting Soviet art happened in the margins. Artists like Alexander Deineka created images of Soviet life that were genuinely inspiring – athletes, workers, young people building a new world. Even when these works served the state’s purposes, they also captured something real about Soviet society’s energy and optimism.

Portrait painting continued throughout the Soviet period, often in ways that subverted official ideology. Artists would paint “official” portraits that satisfied the censors while embedding subtle criticisms or alternative interpretations. A portrait of a factory worker might celebrate labor while also hinting at its human costs. A landscape might glorify Soviet agriculture while also mourning the traditional way of life it had replaced.

The annoying thing about studying Soviet art is separating the genuine artistic achievement from the political context. Some works that were created as propaganda have genuine artistic merit. Others that were created in opposition to the regime are mainly interesting as historical documents. The best Soviet artists managed to create work that functioned on both levels.

Contemporary Russian Art and Identity

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian art went through another identity crisis. With the old ideological frameworks gone, artists had to figure out what it meant to be Russian in the modern world. Some embraced Western contemporary art styles, others returned to traditional Russian themes, and many tried to find new ways to combine local and global influences.

Contemporary Russian art is incredibly diverse, but certain themes keep recurring. Many artists are grappling with the Soviet legacy – trying to understand what that period meant for Russian culture and identity. Others are exploring the tension between Russia’s European heritage and its Eurasian geography. Still others are examining the role of the Orthodox Church in contemporary Russian society.

Artists like Ilya Kabakov have gained international recognition by creating installations that explore the psychology of Soviet and post-Soviet life. Others like AES+F create video works that examine Russia’s place in the globalized world. Photography has become particularly important, with artists documenting the rapid changes in Russian society.

But contemporary Russian art faces real challenges. The government has become increasingly hostile to art that it perceives as critical or foreign-influenced. Some artists have been prosecuted, others have chosen exile. The art world has become another battleground in Russia’s ongoing culture wars.

The Digital Age and New Portraits

Social media has created new forms of portraiture that are reshaping how Russians see themselves. Instagram portraits, TikTok videos, and digital art are creating new visual languages for exploring identity. Young Russian artists are using these platforms to create work that bypasses traditional gatekeepers and reaches audiences directly.

Digital art is also allowing for new forms of collaboration and experimentation. Artists can work with programmers, musicians, and writers to create multimedia experiences that wouldn’t have been possible in earlier eras. Virtual reality is creating new possibilities for immersive art experiences.

But the digital age also presents challenges. The global nature of internet culture can make it harder for local artistic traditions to survive and thrive. The speed of digital communication can make it difficult for complex artistic ideas to develop and mature.

Regional Voices and Diverse Identities

One of the most exciting developments in contemporary Russian art is the emergence of strong regional voices. Artists from Siberia, the Caucasus, and other non-Russian regions are creating work that challenges the Moscow-centered view of Russian culture. These artists are exploring what it means to be Russian when you’re not ethnically Russian, or what it means to be from Russia when your primary cultural identification is with a different tradition.

This regionalism is creating a more complex and interesting picture of Russian identity. Instead of a single, monolithic culture, we’re seeing recognition of Russia as a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural society with many different ways of being Russian.

Indigenous artists are reclaiming traditional cultural practices while also engaging with contemporary art forms. Muslim artists are exploring how Islamic culture fits into the broader Russian context. Jewish artists are examining the complex history of Jewish life in Russia.

Art Markets and Cultural Diplomacy

Russian art has become a significant presence in the global art market. Collectors around the world are buying Russian contemporary art, and Russian artists are exhibiting in major international venues. This global success is changing how Russian art is perceived both inside and outside Russia.

But the art market also creates new pressures. Artists may feel compelled to create work that appeals to international collectors rather than exploring themes that are meaningful to Russian audiences. The high prices paid for some Russian art can create distortions in the local art scene.

Cultural diplomacy has become another important factor. The Russian government has used art exhibitions as tools of soft power, showcasing Russian culture in an attempt to improve the country’s international image. But this instrumentalization of art can also constrain artistic freedom.

Quick Takeaways

- The global success of Russian art creates new opportunities but also new pressures that may change the character of Russian artistic culture.

- Russian art has always been about more then just aesthetics – its been a tool for building and defining national identity across multiple historical periods.

- Portrait painting emerged as a particularly powerful medium for exploring what it means to be Russian, from icon painting through contemporary digital art.

- The tension between local traditions and global influences has been a constant theme in Russian art, producing some of the world’s most innovative artistic movements.

- Collectors and institutions have played crucial roles in shaping Russian artistic culture, often serving as alternative power centers to state authority.

- Contemporary Russian art faces significant challenges from both government restrictions and market pressures, but continues to produce compelling work that engages with questions of identity and belonging.

- Regional and ethnic diversity within Russia is creating new artistic voices that complicate simple narratives about Russian cultural identity.

The Future of Russian Art

Where does Russian art go from here? That’s impossible to predict, but certain trends seem clear. Technology will continue to create new possibilities for artistic expression. The tension between local and global influences will probably intensify rather than resolve. Questions about Russian identity will remain central to the country’s artistic culture.

What seems certain is that Russian art will continue to evolve. It always has. From medieval icons to avant-garde abstractions to contemporary digital installations, Russian artists have consistently found new ways to explore what it means to be Russian. They’ve never been content to just copy what’s happening elsewhere – they’ve always insisted on finding their own voice.

I learned this when I started studying Russian art seriously – you can’t seperate the art from the history, and you can’t understand the history without looking at the art. Every major period of Russian history has produced distinctive artistic responses, and those artistic responses have, in turn, influenced how Russians understand themselves.

The future will probably bring new challenges and new opportunities. Political pressures may constrain some forms of artistic expression while opening up others. Economic changes will affect how art is produced and consumed. Cultural globalization will create new possibilities for cross-cultural dialogue while also threatening local traditions.

But if history is any guide, Russian artists will find ways to respond creatively to whatever circumstances they face. They’ll continue to use their art to explore questions of identity, belonging, and meaning. And in doing so, they’ll continue to shape not just Russian culture, but global artistic culture as well.

Art has always been one of Russia’s great gifts to the world. From the spiritual depth of icon painting to the revolutionary innovations of the avant-garde to the complex engagements with modernity in contemporary work, Russian art has consistently pushed boundaries and opened new possibilities. That tradition seems likely to continue, whatever challenges the future may bring.

Frequently Asked Questions

What makes Russian art different from Western European art? Russian art has consistently blended local traditions with international influences, creating distinctive syntheses that reflect Russia’s unique position between Europe and Asia. The emphasis on spiritual themes, social commentary, and collective identity has remained stronger in Russian art than in much Western art, even during periods of heavy European influence.

Who are the most important Russian artists people should know about? Key figures include Andrei Rublev (medieval icons), Ilya Repin (19th-century realism), Wassily Kandinsky (abstract art), Kasimir Malevich (suprematism), and Marc Chagall (modernist fantasy). Each represents a different period and approach to Russian artistic identity, and understanding their work provides insight into broader cultural developments.

How did Soviet art differ from earlier Russian art? Soviet art was more explicitly political and ideologically driven than earlier periods, though it maintained some continuity with Russian realist traditions. The state exercised much greater control over artistic production, but artists also found ways to work within and around these constraints to create meaningful work.

What role did art collectors play in developing Russian cultural identity? Collectors like Pavel Tretyakov were crucial in creating institutions where Russian art could be displayed and celebrated. They provided financial support for artists, commissioned important works, and created public spaces where Russians could encounter their cultural heritage. Their impact on Russian artistic culture was enormous.

How has contemporary Russian art responded to globalization? Contemporary Russian artists are navigating between local traditions and global art trends, often creating work that speaks to both Russian and international audiences. Some embrace global contemporary art practices while others deliberately emphasize Russian themes and techniques. The result is a diverse artistic landscape that reflects Russia’s complex relationship with the modern world.