In the vibrant heart of Russian culture lies a profound connection between its spirited national festivals and a rich, distinct artistic tradition. More than just annual celebrations, festivals like the raucous Maslenitsa and the mystical Ivan Kupala Day served as the soil from which a unique visual language grew. This art, deeply rooted in folk traditions, pagan history, and Orthodox faith, captures the very essence of the Russian soul—its capacity for immense joy, deep spirituality, and a resilient connection to the land. From the simple charm of folk prints to the grand, celebratory canvases of master painters, the story of Russian art is inextricably linked to the rhythm of its national festivities.

Quick Answer

Russian national festivals and art share a deeply symbiotic relationship, where the country’s visual culture draws profound inspiration from its ancient celebrations. Seasonal festivals with pagan roots, like Maslenitsa (farewell to winter) and Ivan Kupala (summer solstice), have fueled a distinct artistic identity. This is expressed through traditional folk crafts like lubok prints and Palekh miniatures, as well as in the high art of painters like Boris Kustodiev, whose canvases immortalized the joyous, chaotic, and colorful spirit of these deeply-rooted cultural events.

From Pagan Rites to Imperial Splendor: A Timeline of Festive Expression

The origins of Russia’s most cherished festivals stretch back to pre-Christian, pagan times, when Slavic tribes lived in close harmony with the cycles of nature. Maslenitsa, or “Pancake Week,” began as a celebration of the vernal equinox, a joyous farewell to the harsh winter and a welcoming of spring’s life-giving warmth. Similarly, Ivan Kupala Day, celebrated at the summer solstice, was a mystical holiday filled with rituals tied to water, fire, and the blooming of miraculous herbs. These early celebrations were not just parties; they were essential rituals for ensuring fertility, purification, and prosperity.

Art from this period was inherently tied to the ritual. Protective symbols were carved into wooden homes, embroidered onto clothing, and painted onto household objects. The forms were simple, powerful, and deeply connected to the earth.

With the arrival of Orthodox Christianity in the 10th century, these pagan holidays were not entirely eradicated. Instead, a unique syncretism occurred. Maslenitsa was absorbed into the Christian calendar as the final week of feasting before the austerity of Great Lent. Ivan Kupala Day became associated with the birth of John the Baptist (Ivan being the Slavic form of John). This blending of beliefs created a layered cultural landscape where ancient rites coexisted with new faith, a duality that became a hallmark of Russian art.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, these traditions began to be captured in new, more narrative art forms. The lubok, a type of popular print characterized by simple graphics and stories, flourished. These inexpensive woodcuts depicted scenes from religious tales, folklore, and everyday life, often with a satirical or moralizing message. Scenes from Maslenitsa—with its fistfights, sleigh rides, and feasting – were a common and popular subject, making art accessible to the masses for the first time.

The Visual Language of Celebration: Defining Features of Festival Art

Russian festival art, whether in the form of a simple wooden toy or a complex painting, shares a distinct visual vocabulary. It is an art of bold expression, vibrant color, and emotional directness.

Key Characteristics:

- Vibrant Color Palette: The art is rarely subtle. Deep reds, brilliant golds, and rich blues dominate, mirroring the decorated sleighs, festive clothing, and painted church domes that define the festival landscape. This use of color is not just decorative; it is symbolic, often tied to religious iconography and folk beliefs about protection and life.

- Narrative Richness: Much like the epic poems (byliny) and fairy tales (skazki) that were recited during long winter nights, the art is story-driven. A Palekh miniature box, for example, doesn’t just show a pretty scene; it illustrates an entire folktale on its tiny surface, with figures in continuous, flowing motion.

- Idealized View of Russian Life: Especially in the works of later painters, festival art presents a romanticized vision of Russia. It is a world of rosy-cheeked peasants, bustling winter markets, and idyllic village life. This was not a documentarian’s view, but a celebration of a national ideal—a prosperous, joyous, and spiritually unified community.

- Fusion of the Sacred and the Profane: A quintessential feature is the blending of religious and secular themes. A depiction of Maslenitsa might show riotous merry-making in the shadow of a beautiful Orthodox church, capturing the unique duality of a holiday that is both a pagan farewell to winter and a Christian preparation for Lent.

Masters of Merriment: The Artists Who Painted Russia’s Soul

While folk art was largely anonymous, a number of celebrated artists drew heavily from the well of national festivals and traditions, elevating them into the realm of high art.

Boris Kustodiev (1878-1927)

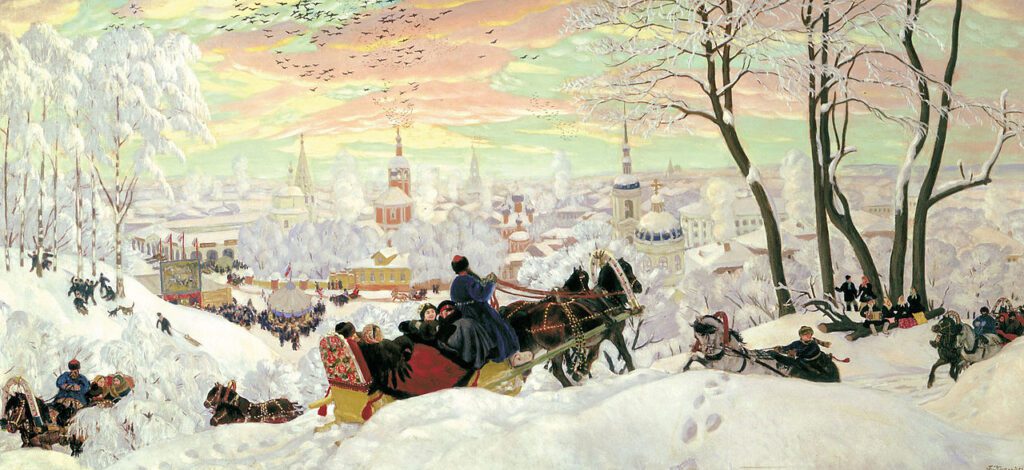

No artist is more associated with the joyous spirit of Russian festivals than Boris Kustodiev. Despite being confined to a wheelchair for the last 15 years of his life due to tuberculosis of the spine, his paintings are an explosion of life, color, and movement. His multiple works titled Maslenitsa are considered the definitive depictions of the holiday. Painted from memory and imagination, they are panoramic visions of a fairy-tale winter city, teeming with troikas, bustling crowds, and snow-covered church domes under a festive sky. Kustodiev’s art is a testament to his enduring love for a Russia that was rapidly disappearing, a vibrant world of merchants, folk traditions, and communal celebration.

Ivan Bilibin (1876-1942)

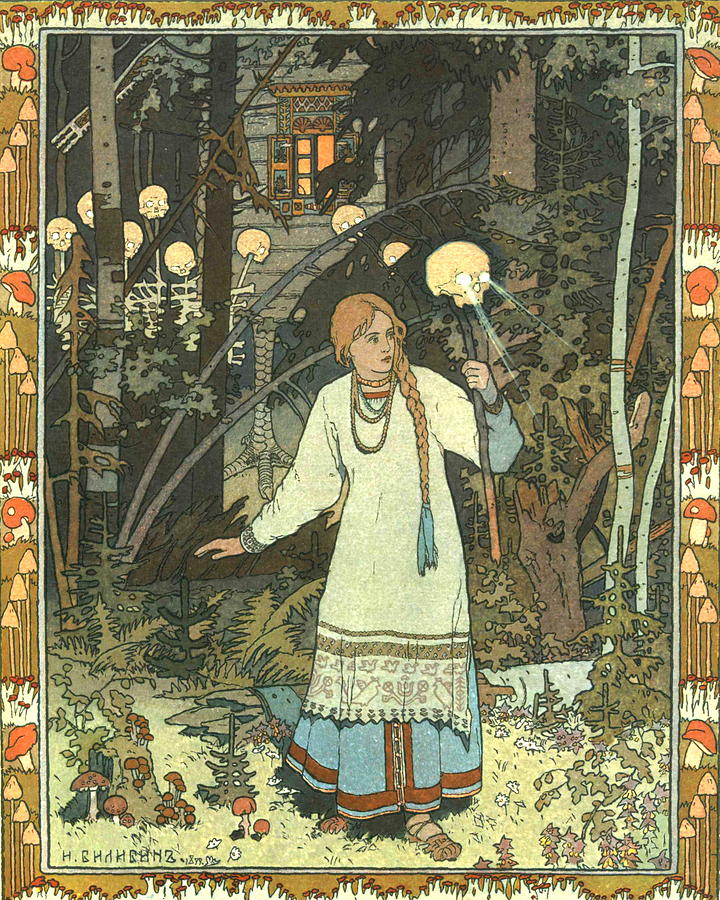

A key member of the Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) movement, Ivan Bilibin was instrumental in reviving interest in old Russian folklore and crafts. He is most famous for his enchanting illustrations of Russian fairy tales. His style is highly graphic and ornamental, directly inspired by the composition of lubok prints and the intricate details of folk embroidery. By bringing characters like Vasilisa the Beautiful and the Firebird to life with such distinctive style, Bilibin helped codify a national aesthetic that was both modern and deeply traditional.

and manuscript art.

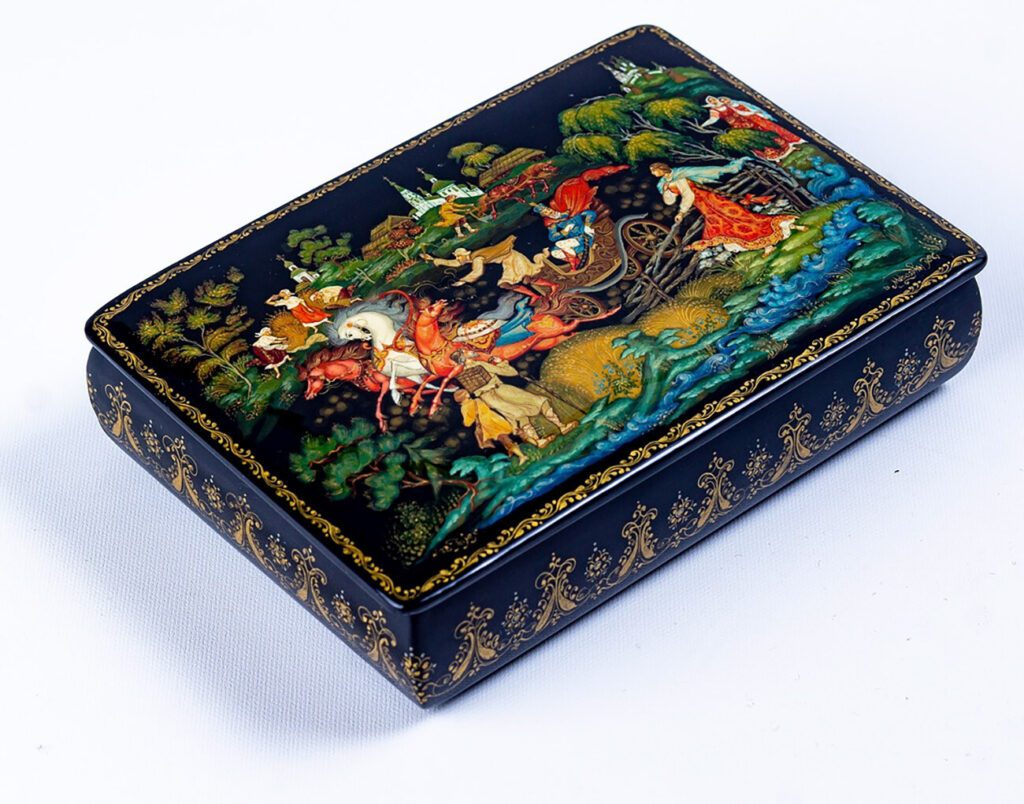

Artists of the Lacquer Miniature

After the 1917 Revolution, the long tradition of icon painting was officially suppressed. In villages like Palekh, Mstera, and Kholui, former icon painters adapted their exquisite skills to a new medium: lacquerware. They began painting miniature scenes on papier-mâché boxes, using the same egg tempera techniques and fine gold detailing that had once adorned religious icons. Instead of saints, however, these boxes depicted scenes from folklore, literature, and village life, including festival celebrations. This art form preserved the technical and stylistic heritage of icon painting while transforming it into a new, secular folk tradition.

💰 Did You Know?

During the early Soviet era, the ancient art of Palekh miniature was co-opted for state purposes. Instead of traditional fairy tales, artists were sometimes commissioned to paint scenes of collective farm life, workers’ parades, and other themes of socialist progress, all rendered in the delicate, icon-inspired style.

Notable Works and Crafts: The Tangible Spirit of Celebration

The artistic output inspired by Russian festivals is vast and varied, ranging from simple toys to monumental paintings.

Lubok Prints

These popular prints were the mass media of their day. A lubok from the 18th century, The Mice Are Burying the Cat, is famously interpreted as a satire of Peter the Great’s burial, showcasing the medium’s potential for social commentary. Lubki depicting Maslenitsa were filled with scenes of troika races, ice slides, and feasting, solidifying the visual tropes of the holiday for a wide audience.

Dymkovo Toys

Originating from the village of Dymkovo near Vyatka, these brightly painted clay figures are one of Russia’s oldest folk crafts. Traditionally made by women to be sold at the spring “Whistling Fair,” the figures depict ladies in ornate dresses, proud gentlemen, animals, and scenes from village life. Their brilliant colors and whimsical patterns are a pure expression of folk joy.

Palekh and Fedoskino Miniatures

These small, exquisitely painted lacquer boxes represent the pinnacle of Russian folk craftsmanship. While both are famous for miniature painting, they use different techniques. Fedoskino artists use oil paints, often achieving a realistic, portrait-like quality. Palekh artists, descended from icon painters, use egg tempera and gold leaf on a black lacquer background, creating luminous, otherworldly scenes from Russian folklore.

From Tsarist Russia to Today: The Enduring Legacy

The art born from Russian festivals has proven remarkably resilient. During the Soviet era, folk art was sometimes suppressed as a religious or backward vestige of the past. However, it was also sometimes celebrated and institutionalized as a representation of the “people’s culture,” albeit stripped of its spiritual context.

Today, there is a renewed interest in these traditions. Festivals like Maslenitsa are once again celebrated with huge public events, both in Russia and in diaspora communities around the world. Folk crafts are preserved in institutions like the All-Russian Decorative Art Museum and are a source of national pride. The works of Kustodiev and Bilibin are beloved classics, held in the country’s most prestigious museums, including the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg.

The enduring appeal of this art lies in its powerful connection to a collective identity. It is a visual record of a culture’s deepest values: community, resilience, a profound connection to the seasons, and an unwavering capacity to find and create joy, even in the depths of the longest winter.

Essential Points About Russian Festival Art

- Pagan Roots, Christian Identity: Core festivals like Maslenitsa and Ivan Kupala Day originated in pre-Christian Slavic traditions tied to the seasons and were later merged with the Orthodox Christian calendar.

- Art for the People: Folk art forms like the lubok (popular print) and Dymkovo toys made visual art accessible and relevant to all social classes, depicting scenes of daily life, folklore, and celebration.

- A Story in Every Object: Much of this art is narrative, telling stories from fairy tales, epic poems, and religious texts. Lacquer miniatures, in particular, are known for their complex, detailed storytelling.

- Boris Kustodiev: The Master of Maslenitsa: No artist is more famous for capturing the spirit of Russian festivals. His paintings of Maslenitsa are iconic, idealized visions of a joyous, pre-revolutionary Russia.

- From Icons to Folk Art: The ancient and highly skilled tradition of Orthodox icon painting directly influenced the development of secular folk arts, most notably Palekh lacquer miniatures, after the Russian Revolution.

- A Language of Bold Color and Joy: The defining aesthetic is one of vibrancy and emotional expression, using brilliant colors and dynamic compositions to convey the energy of celebration.

- Preservation and Pride: This artistic heritage is carefully preserved in Russia’s major museums, such as the State Tretyakov Gallery and the State Russian Museum, and continues to be a symbol of national identity.

- Enduring Legacy: Despite periods of suppression, especially during the Soviet era, these folk traditions have survived and are once again celebrated as an essential part of Russian culture.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Q – What is the main purpose of Russian festival art?

- A – The main purpose of Russian festival art is to capture and celebrate the collective spirit of the nation. It serves to express joy, preserve cultural memory, and reinforce a shared identity rooted in seasonal rites, folklore, and religious faith. It is both a decoration for and a reflection of communal celebration.

- Q – How did Peter the Great’s reforms affect traditional Russian art?

- A – Peter the Great’s Westernizing reforms in the 18th century introduced European artistic styles, like Baroque portraiture and secular painting, to the Russian nobility. While this created a formal, academic art tradition, older folk art forms like the lubok continued to thrive among the common people, preserving a distinct national aesthetic.

- Q – What do bears symbolize in Russian folk art and festival imagery?

- A – In Russian folklore and art, the bear is a powerful and dualistic symbol. It represents both raw, untamed nature and the spirit of Russia itself—strong, formidable, and sometimes clumsy. In festival imagery, performing bears were common attractions, embodying the festive spirit where the wildness of nature is briefly tamed for human entertainment.

- Q – Why is Boris Kustodiev considered the ultimate painter of Russian festivals?

- A – Boris Kustodiev is considered the ultimate painter of Russian festivals because his works, particularly his series on Maslenitsa, perfectly encapsulate an idealized, joyous vision of pre-revolutionary Russian life. Despite his personal suffering, he painted vibrant, panoramic scenes brimming with life, color, and nostalgia, defining the festival’s image in the popular imagination.

- Q – Where can I see authentic Russian folk art and festival crafts today?

- A – Major collections of authentic Russian folk art can be seen at the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, and the All-Russian Decorative Art Museum in Moscow. These institutions house extensive collections of lubok prints, lacquer miniatures, traditional costumes, and other historical crafts.