Russian Landscape Art: When Nature Becomes the Soul of a Nation

Russian landscape painting isn’t just about pretty scenery – it’s about identity, belonging, and what it means to be Russian. When you look at a canvas by Isaac Levitan or Ivan Shishkin, you’re not just seeing trees and fields. You’re seeing the heart of a nation that found itself through its connection to the land.

This artistic movement transformed how Russians saw themselves and how the world saw Russia. Rather than copying European masters, these painters created something entirely their own – landscapes that could only be Russian.

The Early Struggle: Breaking Free from European Influence

When Russian Art Looked Everywhere But Home

For much of the 18th and early 19th centuries, Russian artists painted landscapes that could have been anywhere in Europe. They learned techniques from Italian masters, Dutch painters, and French academies. The result? Russian scenes that somehow looked suspiciously like the Italian countryside.

Alexei Venetsianov (1780-1847) changed all that. This largely self-taught artist became the founder of authentic Russian landscape painting. Instead of grand, idealized scenes, he painted modest rural Russia – peasants working, simple wooden houses, muddy roads that actually existed.

Venetsianov believed that art should serve literature and the enlightenment of the people. For him, painting wasn’t just decoration – it was a tool for cultural awakening. His students would carry this philosophy forward, creating what we now recognize as distinctly Russian landscape art.

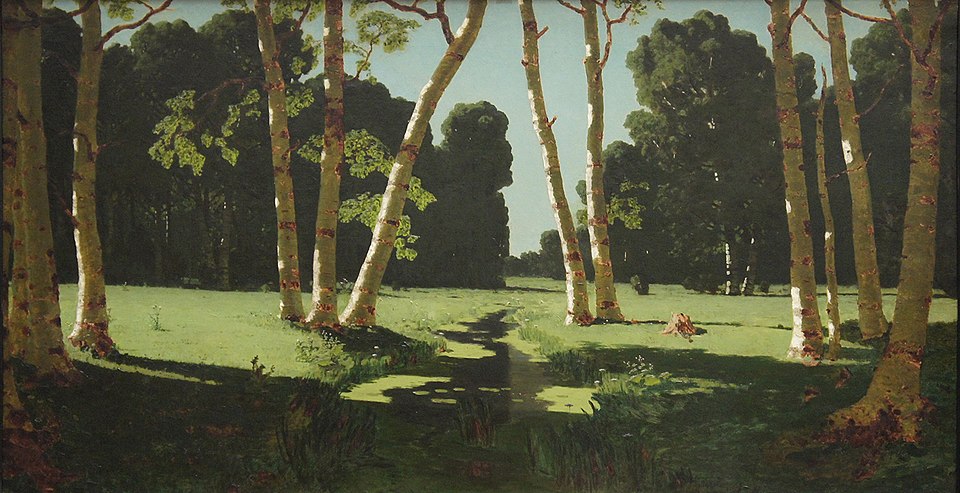

The Birth of Plein Air in Russia

Working directly from nature – plein air painting – revolutionized Russian landscape art. Instead of composing scenes in studios based on sketches, artists began capturing light, weather, and atmosphere directly outdoors.

This wasn’t just a technical shift. It was philosophical. By painting nature as they actually experienced it, Russian artists began discovering what made their homeland unique. The quality of light filtering through birch forests, the vastness of the steppes, the melancholy beauty of autumn – these became the building blocks of Russian visual identity.

The Peredvizhniki: Art for the People

Wandering Artists, Wandering Ideas

The Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions, known as the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers), formed in 1870 when a group of students walked out of the restrictive Imperial Academy of Arts. They wanted to bring art to ordinary people, traveling throughout the Russian Empire with exhibitions.

These artist-rebels believed art should reflect real Russian life, not academic ideals imported from Western Europe. Their landscape paintings celebrated the beauty of the Russian countryside while subtly critiquing social conditions.

The Wanderers gave Russian landscape painting its national character. As one critic noted, people of other nations could now recognize a distinctly Russian landscape – something that had never existed before.

Levitan’s Melancholy Masterpieces

Isaac Levitan (1860-1900) created landscapes that seemed to sing with emotion. Born into poverty in a Jewish family, he studied at the Moscow School of Painting despite facing discrimination. His teacher Alexei Savrasov recognized his extraordinary talent and invited him into the landscape class.

Levitan painted the Russian countryside with such poetic sensitivity that even his contemporaries called his later works “songs without words.” His friend Anton Chekhov wrote that Levitan’s landscapes had “wonderful simplicity and clarity of motif, such as no one had ever reached before.”

The Volga River became Levitan’s “place of power.” Paintings like “Evening on the Volga” (1888) and “Evening Bells” (1892) captured not just the physical beauty of Russia’s greatest river, but something deeper – the rhythm of Russian life itself.

Shishkin: The Tsar of the Woods

Capturing Every Leaf and Branch

Ivan Shishkin (1832-1898) earned the nickname “tsar of the woods” for his incredibly detailed forest scenes. Unlike Levitan’s poetic approach, Shishkin was a scientific observer of nature. He could paint individual species of trees, bushes, and grasses with botanical accuracy.

His methodical approach created a bridge between academic traditions and emotional connection to Russia’s natural environment. Shishkin didn’t just paint forests – he painted Russian forests, with their specific light, their particular mix of species, their unique character.

“Morning in a Pine Forest” (1889), featuring bears in a misty forest clearing, became one of Russia’s most beloved paintings. It appeared on Soviet candy wrappers, making it probably the most reproduced Russian artwork ever.

The Democratic Forest

What made Shishkin’s work revolutionary wasn’t just technical skill – it was his choice of subjects. He painted ordinary Russian forests, not exotic locations or mythological scenes. These were woods that regular people could recognize, places they might have walked through themselves.

This democratization of landscape art reflected broader social changes. The 1861 abolition of serfdom created new audiences for art – people who wanted to see their own country celebrated on canvas, not idealized versions of foreign lands.

The Psychology of Russian Space

Vastness as Character

Russian landscape painting reflects something unique about the Russian experience – the psychological impact of immense space. Christopher Riopelle, curator at London’s National Gallery, observed that “the emptiness of the country’s vast reaches, the rigours of its climate, the difficulties of transportation, and the intense isolation that long winter months impose, all contribute to a specifically Russian sense of nature.”

This isn’t just geographic description – it’s cultural psychology. Russian artists painted landscapes that conveyed feelings of both freedom and melancholy, hope and resignation. The endless horizons suggested infinite possibility while also emphasizing human smallness.

The Concept of Rodina

The Russian word “rodina” has no exact English equivalent. It means homeland, but carries deeper emotional weight – a concept of place that encompasses birth, family, identity, and belonging. Russian landscape painters were essentially painting rodina – not just geography, but emotional and spiritual territory.

Artists like Arkhip Kuindzhi created landscapes that glowed with almost mystical light. His “Moonlit Night on the Dnieper” (1880) featured such luminous effects that viewers initially thought the canvas was lit from behind. This wasn’t just technical showmanship – it was an attempt to capture the spiritual essence of the Russian landscape.

Literary Connections: Tolstoy and the Painted Word

When Writers Paint and Painters Write

The golden age of Russian landscape painting coincided with the era of great Russian literature. Leo Tolstoy, whose lifespan (1828-1910) bracketed the movement, wrote with distinctly painterly sensibility.

In “Childhood, Boyhood and Youth,” Tolstoy described landscape with the eye of a visual artist: “The brilliant yellow field was bounded on one side only by the bluish forest, which seemed to me then a very distant and mysterious place beyond which either the world came to an end or some uninhabited regions began.”

This cross-pollination between visual and literary arts strengthened both. Painters like Levitan were close friends with writers like Chekhov. They shared approaches to capturing the Russian character through careful observation of daily life and natural surroundings.

Landscape as Political Statement

During periods of censorship, landscape painting provided a safe way to express national pride and critique social conditions. Unlike genre paintings showing social problems directly, landscapes could suggest political ideas through mood and symbolism.

Levitan’s “Vladimirka Road” (1892) shows the infamous route along which prisoners were marched to Siberian exile. The painting doesn’t show prisoners or guards – just an empty road disappearing into the distance. Yet every Russian viewer understood its meaning. Through landscape, Levitan created one of the most powerful anti-authoritarian statements in Russian art.

Technical Innovation: Color and Light

Breaking the Academic Palette

Early Russian landscape painting followed European color conventions – dark, earthen palettes dominated by browns and ochres. The Peredvizhniki revolutionized this approach, choosing lighter, more naturalistic colors that reflected Russia’s actual appearance.

This wasn’t just aesthetic choice – it was cultural assertion. By painting Russian light as it actually appeared, rather than filtering it through European artistic conventions, Russian artists declared their independence from Western artistic colonialism.

The Science of Russian Light

Russian artists became obsessed with accurately capturing their country’s unique light conditions. The long twilight of northern summers, the brilliant snow-reflected light of winter, the golden tones of birch forests in autumn – these became signature elements of Russian landscape art.

Kuindzhi’s experiments with color and light influenced an entire generation. His students learned to see the landscape as a constantly changing interplay of atmospheric effects rather than a collection of static objects.

Regional Variations: From Steppes to Forests

The Poetry of Different Landscapes

Russia’s vast territory provided endless subject matter for landscape painters. Each region developed its own visual character within the broader Russian landscape tradition.

The central Russian forests, with their birches and pines, became the most iconic. But artists also celebrated the endless steppes of the south, the dramatic Caucasus mountains, the mysterious northern tundra, and the mighty rivers that connected these diverse regions.

Urban vs. Rural Identity

The annoying thing about studying Russian landscape painting is how it reinforces stereotypes about Russia being purely rural. In reality, Russia was rapidly industrializing during this period. Yet landscape painters consistently chose to emphasize the country’s connection to traditional rural life.

This wasn’t naive romanticism – it was conscious cultural choice. As Russia modernized, artists used landscape painting to preserve and celebrate values they saw disappearing. The paintings became repositories of cultural memory.

International Recognition: Russia’s Artistic Coming of Age

From Provincial to Pioneering

For most of the 19th century, Russian art was considered provincial by Western European standards. The 2004 National Gallery exhibition “Russian Landscape in the Age of Tolstoy” changed that perception dramatically.

This major show featured 70 of Russia’s greatest landscape paintings, many never before seen outside Russia. It revealed to Western audiences the sophistication and emotional depth of Russian landscape art. Critics who expected quaint provincial paintings instead discovered a mature artistic movement with its own aesthetic philosophy.

Influence on World Art

Russian landscape painting began influencing international art by the early 20th century. The combination of technical realism with emotional intensity created a template that artists worldwide would adapt to their own national contexts.

The Russian approach – using landscape to explore national identity rather than just depicting pretty scenery – became a model for artistic movements in other countries seeking to establish their own cultural independence.

Modern Legacy: Digital Age Meets Traditional Vision

Contemporary Artists and Russian Traditions

Today’s Russian landscape painters still work within traditions established by Levitan and Shishkin. Artists like Zufar Bikbov emphasize the continuing relevance of Russian realist techniques, teaching that emotional connection to place remains as important as technical skill.

Modern digital artists also reference classic Russian landscape styles. AI art generators trained on historical Russian paintings can produce works that capture something of the original movement’s spirit, though obviously lacking the authentic cultural connection.

Museums and Collections

The State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow houses the world’s largest collection of Russian landscape paintings. The State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg contains over 10,000 works spanning the entire development of Russian art. These institutions preserve not just individual artworks but the cultural vision they represent.

Interestingly, some of the most significant Russian landscape collections now exist outside Russia. The Museum of Russian Art in Minneapolis houses the largest collection of Russian realist paintings outside the former Soviet Union – evidence of how these works have found international appreciation.

Collecting and Appreciation Today

Market Dynamics

Russian landscape paintings have become increasingly valuable in international art markets. Works by major artists like Levitan and Shishkin regularly sell for millions of dollars at auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s.

However, many excellent works by lesser-known artists remain relatively affordable. Regional museums and private collectors continue discovering forgotten masters whose work equals that of more famous names.

Recognition Challenges

One persistent challenge is Western art history’s continued focus on avant-garde movements. Russian landscape painting, because it emphasized realism over innovation, often gets overlooked in surveys of world art. This creates opportunities for collectors but limits broader appreciation of the movement’s significance.

Technical Mastery: How They Did It

Plein Air Techniques in Harsh Conditions

Russian landscape painters perfected techniques for working outdoors in challenging conditions. They developed methods for painting in sub-zero temperatures, during brief Arctic summers, and in the changing light of northern latitudes.

These technical adaptations became part of the movement’s character. The urgency of capturing fleeting effects in difficult conditions contributed to the emotional intensity of Russian landscape art.

Studio Finishing

Most Russian landscape painters combined plein air studies with studio work. They would create detailed oil sketches outdoors, then develop larger, more finished paintings in their studios during winter months.

This hybrid approach allowed them to combine the authenticity of direct observation with the careful composition and refined technique possible only in controlled studio conditions.

Quick Takeaways

- Russian landscape painting transformed how an entire culture saw itself through art. By rejecting European artistic colonialism and painting their homeland with honest observation and deep emotion, Russian artists created one of history’s most psychologically powerful artistic movements.

- The best Russian landscapes work on multiple levels – as accurate depictions of specific places, as expressions of national character, and as explorations of the human relationship with nature. They prove that regional art can achieve universal significance.

- These painters understood that landscape isn’t just scenery – it’s the physical manifestation of cultural identity. Their work continues inspiring artists worldwide who seek to capture the essence of their own homelands.

- The movement’s emphasis on emotional authenticity over technical innovation offers valuable lessons for contemporary artists. Sometimes the most powerful art comes not from pushing boundaries but from deeply understanding your subject.

- Russian landscape painting remains relevant because it addresses fundamental questions about place, identity, and belonging that concern people everywhere.

Conclusion

Russian landscape painting succeeded because it was never really about landscape – it was about identity. These artists understood that place shapes character, that geography influences psychology, that the land we come from becomes part of who we are.

When Levitan painted a muddy road or Shishkin detailed every needle on a pine tree, they weren’t making documentary records. They were creating visual poetry about what it means to belong somewhere, to feel connected to a particular piece of earth.

I learned this when I first saw a Levitan painting in person – the way he could make an ordinary field seem to contain the entire emotional history of Russia. That’s not technique you can teach in art school. That’s cultural memory made visible.

The lasting power of Russian landscape painting lies in its ability to make viewers feel something essential about place and belonging, even if they’ve never set foot in Russia. Great art transcends its original context while remaining rooted in specific cultural soil.

These paintings remind us that nationalism in art doesn’t have to be aggressive or exclusionary. It can be celebration, appreciation, and deep love for the particular characteristics of home.

FAQs

What makes Russian landscape painting different from European traditions? Russian landscape painting emphasized emotional connection to specific places rather than idealized compositions. While European masters often painted imaginary or heavily romanticized scenes, Russian artists focused on authentic depictions of their homeland’s unique character, light, and atmosphere.

Why did Russian landscape painting become so important for national identity? During the 19th century, Russia was developing its cultural independence from Western European influence. Landscape painting provided a way to celebrate uniquely Russian characteristics – the vastness of the steppes, the quality of northern light, the character of Russian forests – that couldn’t be found elsewhere.

Who were the most important Russian landscape painters? Isaac Levitan created the most emotionally resonant Russian landscapes, earning comparison to great poets. Ivan Shishkin became famous for incredibly detailed forest scenes. Alexei Venetsianov founded the tradition by turning away from European influences. The Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) movement democratized landscape art throughout Russia.

How did Russian writers influence landscape painting? Writers like Tolstoy and Chekhov shared close friendships with painters like Levitan. They influenced each other’s approaches to capturing Russian character through careful observation of daily life and natural surroundings. Both groups used their art to explore questions of national identity and social change.

Where can you see the best Russian landscape paintings today? The State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow houses the world’s largest collection. The State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg contains over 10,000 Russian artworks. Outside Russia, the Museum of Russian Art in Minneapolis has the largest collection of Russian realist paintings, while many major Western museums feature important examples.