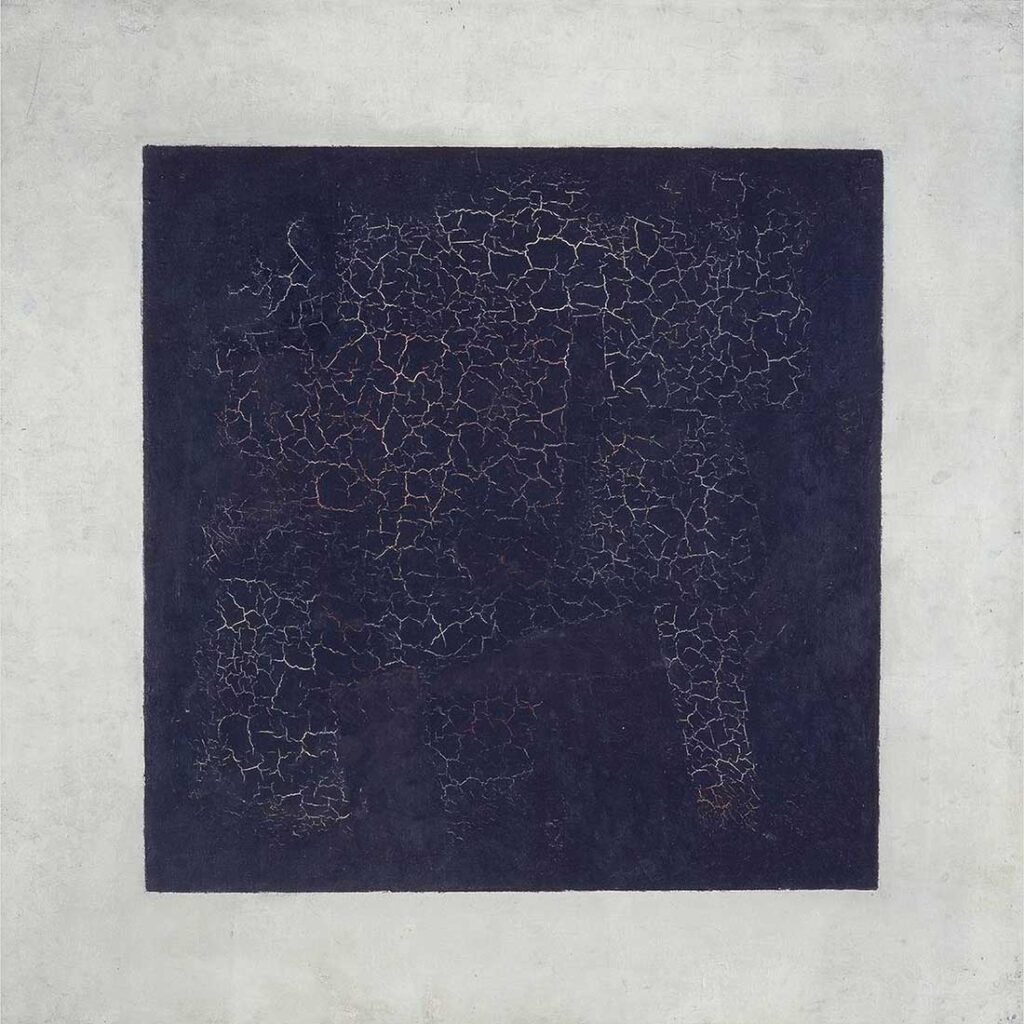

There’s this moment in art history – 1915, St. Petersburg – when Kazimir Malevich hung a painting of a black square on a white canvas in the corner of a gallery. Not in the regular spot, but in the place where Russian families traditionally put religious icons. People lost there minds. Some thought it was brilliant. Others thought he’d completely lost it.

That painting kicked off Suprematism art, and honestly, it’s one of those movements that still confuses people today. Which sort of makes sense – your looking at geometric shapes on a canvas and your supposed to feel something profound about the “supremacy of pure feeling.” But stick with me here, because once you get what Malevich was trying to do, Suprematism art starts to make alot more sense.

What Actually Is Suprematism Art

So Suprematism art is basically this: take away everything recognizable from painting. No landscapes, no portraits, no bowls of fruit. Just pure geometric forms – squares, circles, rectangles, crosses – painted in a limited color palette. Malevich called it the “zero degree” of painting. Like, he wanted to strip art down to its most basic elements and see what was left.

The whole point was to create art that expressed pure feeling without relying on the real world. Before Suprematism, even abstract art usually referenced something – a person, a place, an object. Malevich said screw that, lets make art that exists entirely on it’s own terms.

He developed this idea around 1913 while working on stage designs for a Russian Futurist opera called “Victory Over the Sun.” The opera was pretty wild – all about destroying the sun and liberating humanity from nature. Malevich created these costume sketches with bold geometric shapes, and somewhere in that process, the black square appeared. He knew immediately he’d stumbled onto something big.

The 1915 Exhibition That Changed Everything

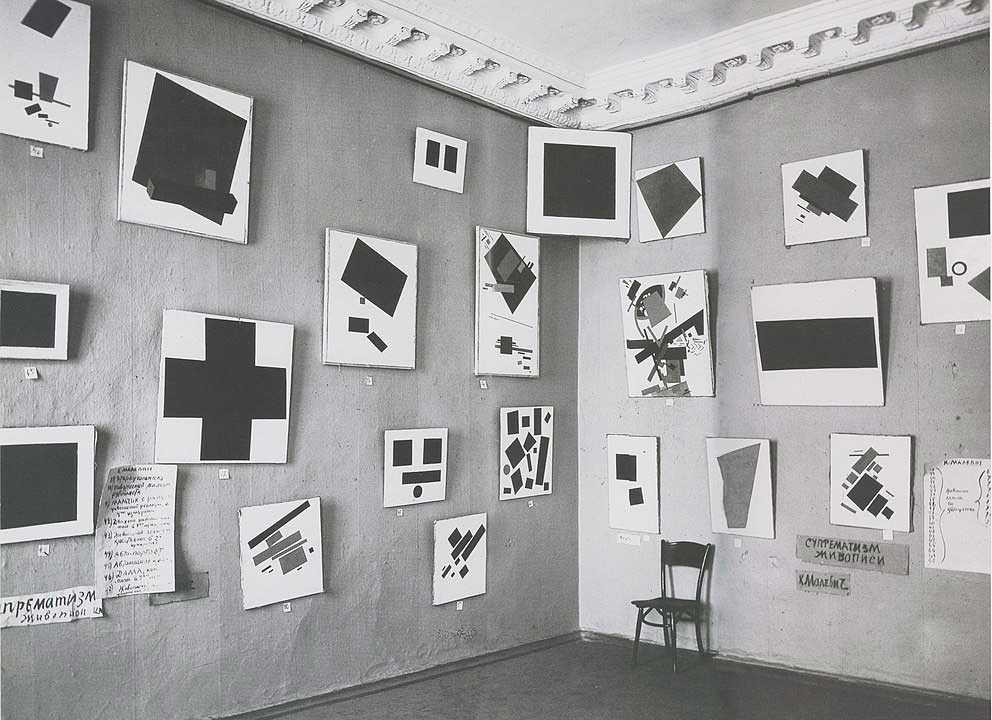

In December 1915, Malevich unveiled his Suprematist works at an exhibition called “The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10” in Petrograd. The name itself was provocative – that “0,10” part was Malevich’s way of saying this was the zero point, the beginning of something entirely new.

He showed 39 paintings. Black Square was the star, hung high in the corner where Orthodox icons would traditionally sit in a Russian home. This wasn’t an accident – Malevich wanted people to see Suprematism art as spiritually significant, like a new kind of religion for the modern age.

According to reports from the time, about 2,500 people visited the exhibition. Many were baffled, some were angry, but nobody could ignore it. Art critic Alexander Benois wrote that it felt like standing at a “dead end” – he couldn’t figure out where art could possibly go from there.

How Suprematism Art Actually Worked

Malevich wasn’t just throwing random shapes on a canvas. He developed a whole grammar of Suprematism art based on fundamental forms. The square represented pure feeling. The circle meant movement and dynamism. The cross symbolized spiritual energy or something like that – Malevich’s explanations could get pretty mystical.

He worked through three phases:

First came the black period – stark geometric forms on white backgrounds. This is when Black Square, Black Circle, and Black Cross were created. The contrast was extreme, the forms were simple, and the impact was immediate.

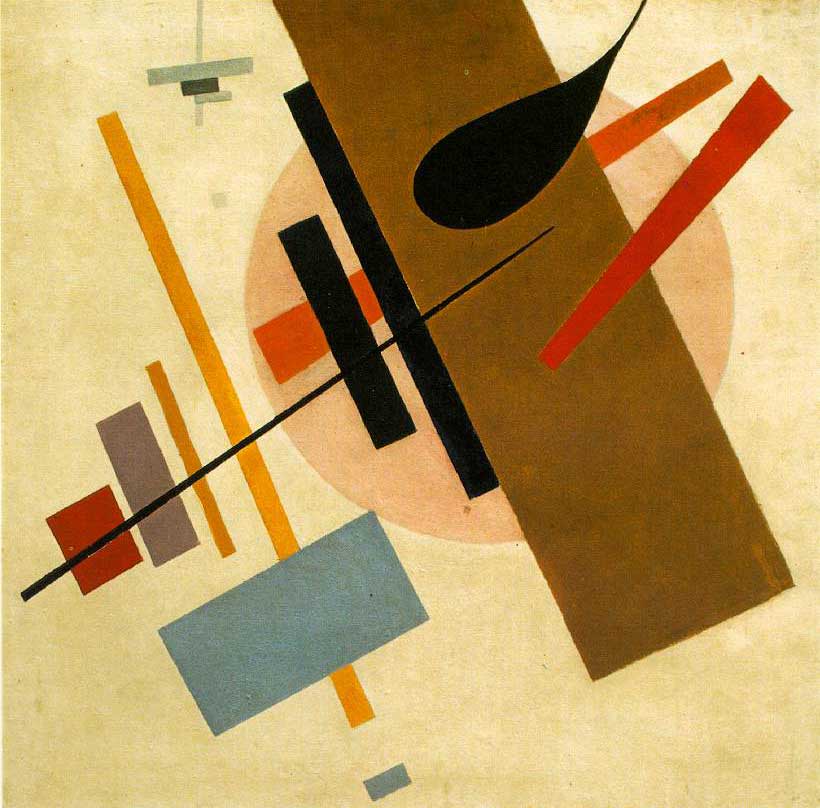

Then the colored period around 1916-17. Malevich started introducing reds, blues, greens, browns. The compositions got more complex – you’d see shapes floating at different angles, creating this sense of movement in space. His painting “Airplane Flying” from this period shows how he started playing with the idea of non-Euclidean geometry, where flat shapes seem to exist in multiple dimensions simultaneously.

The annoying thing about Suprematism is that Malevich kept changing his explanations for what it all meant. In one text he’d talk about pure feeling, in another he’d go on about cosmic consciousness and the fourth dimension. Critics have been arguing about his intentions ever since.

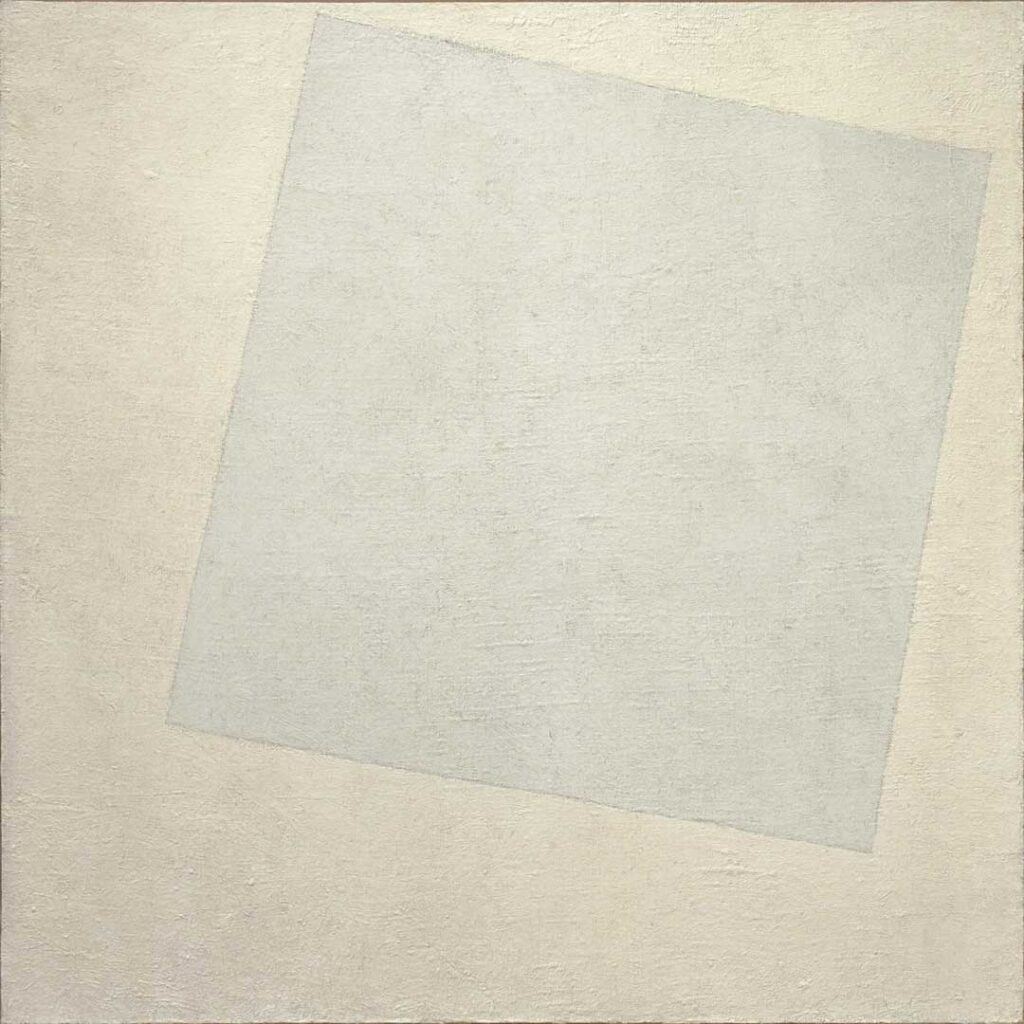

Finally, the white period culminated in “White on White” (1918) – a white square on a slightly different shade of white. At this point, Malevich had basically reduced painting to almost nothing. You could barely see the square. Some people think this was the logical endpoint of Suprematism art; others thought he’d taken the whole thing too far.

Why Russia Was the Perfect Place for This

Russia in the 1910s was going through massive changes. The old tsarist system was crumbling, new political ideas were spreading, and artists felt like they were on the edge of something unprecedented. There was this sense that everything – politics, society, art – could be completely reimagined from scratch.

Malevich wasn’t alone in pushing boundaries. Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov were experimenting with Rayonism. Vladimir Tatlin was moving towards Constructivism. The Russian Futurists were writing poems that deliberately broke grammar rules and made up new words. Everyone was questioning what there medium could do.

This environment gave Malevich the confidence to make such radical moves. In Paris or London, his ideas might of seemed too extreme. In revolutionary Russia, they fit right in with the spirit of total transformation. Though ironically, within a decade, Stalin’s rise would shut down all this experimentation and force artists back into Socialist Realism.

The Influences Behind Suprematism Art

Malevich didn’t create Suprematism art in a vacuum. He’d been closely following European modernism, particularly Cubism and Futurism. When Picasso and Braque broke objects into geometric fragments, Malevich paid attention. When the Italian Futurists talked about speed, dynamism, and breaking with the past, he listened.

But he also drew from Russian sources. Traditional icon painting influenced his use of flat surfaces and bold colors. Russian folk art, with its simple patterns and bright hues, shows up in his earlier work. And he was reading the Russian Formalist poets and critics who argued that language doesn’t transparently represent reality – words are just sounds that we’ve assigned meaning to. If that’s true for language, Malevich reasoned, then painting doesn’t need to represent objects either.

The philosopher Peter Ouspensky was another influence. Ouspensky wrote about the fourth dimension and higher consciousness, ideas that were trendy in avant-garde circles. Malevich latched onto this mystical geometry stuff, believing that Suprematist forms could help people perceive realities beyond the material world.

I learned this when researching for a project – X-ray analysis done in 2015 revealed something wild about the original Black Square. Underneath the black paint, there are two earlier paintings and a written inscription that reads “Negroes battling in a cave.” This was apparently a reference to an 1897 satirical painting by French writer Alphonse Allais. So even Malevich’s most “original” work was sort of responding to something that came before. Art history is messier than the textbooks make it seem.

The Other Artists in the Movement

While Malevich was definately the leader, several other artists joined the Suprematist group. Olga Rozanova stands out – she expanded the color palette and focused intensely on texture. She wanted her paintings to feel like different fabrics. Ivan Kliun, Mikhail Menkov, and Ivan Puni also showed Suprematist works at the 0,10 exhibition.

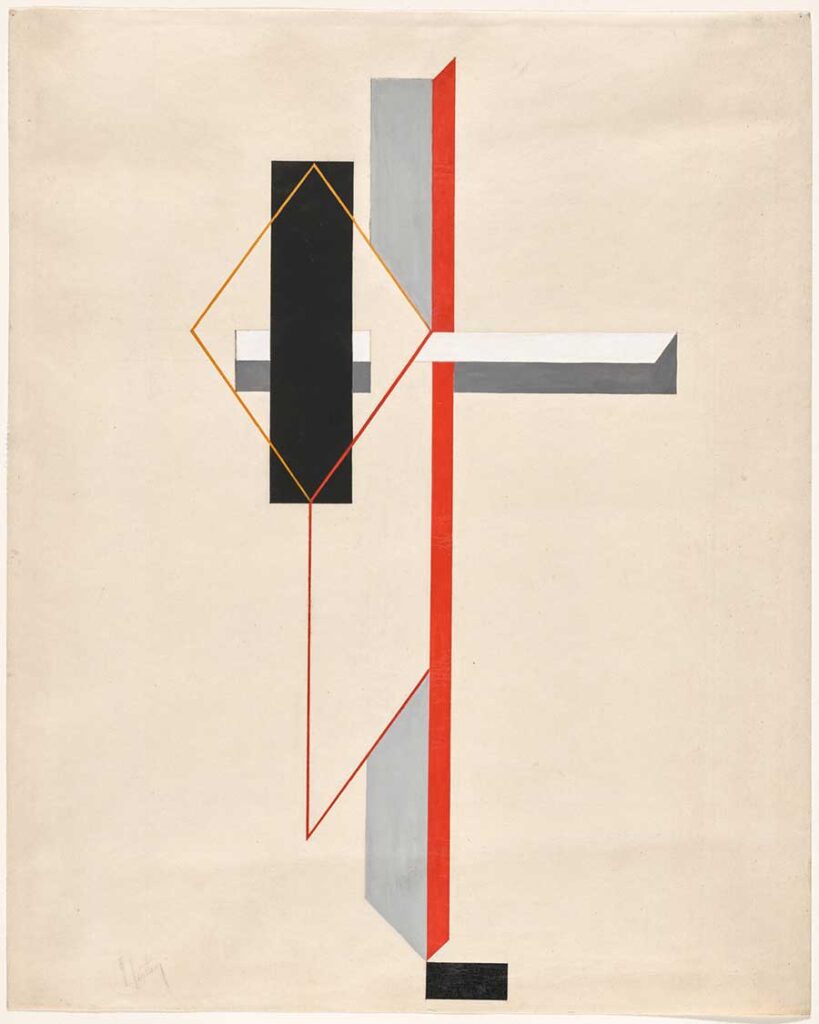

But the most important follower was El Lissitzky. He studied under Malevich and developed what he called “Proun” – a kind of bridge between Suprematism art and architecture. Lissitzky took the geometric forms and started thinking about how they could exist in three-dimensional space, influencing designers and architects across Europe.

When Lissitzky moved to Germany in the 1920s, he brought Suprematist ideas with him. The Bauhaus school absorbed some of these concepts. Piet Mondrian’s De Stijl movement in the Netherlands shared similar interests in geometric abstraction, though Mondrian came to it independently. Even Zaha Hadid, the famous contemporary architect, studied Suprematism and you can see echoes of it in her buildings.

When It All Fell Apart

By the mid-1920s, Suprematism art was losing steam. Stalin’s rise to power changed everything. The Soviet government wanted art that regular workers could understand – heroic paintings of farmers and factory workers, not mystical white squares. In 1934, Socialist Realism became the official style, and abstract art was basically banned.

Malevich tried to adapt. He started painting figurative works again – peasants, workers – but he’d sign them with a tiny black square, like a secret signature. He died in 1935, and his Suprematist works disappeared from public view in Russia for decades.

Meanwhile, the movement’s influence spread worldwide. Approximately 120 of Malevich’s paintings and drawings made there way to museums in Europe and America. The Museum of Modern Art in New York acquired “White on White” in 1935, ensuring that Suprematism art would remain part of the international conversation.

How to Actually Look at Suprematism Art

Here’s what trips people up – you can’t look at Suprematism art the same way you’d look at a Renaissance painting. There’s no story, no symbolism in the traditional sense, no hidden meaning to decode. You’re suppose to experience it directly, emotionally, without intellectualizing.

Start with the colors. Notice how a red square feels different from a black one. Then look at the relationships between forms – how shapes seem to float, advance, or recede in space. Pay attention to texture if you can see the work in person; Malevich varied his brushstrokes deliberately.

Don’t overthink it. If it makes you feel calm, energized, confused, or even annoyed, then its working. Malevich wanted pure emotional responses, not intellectual analysis. Though ironically, he wrote thousands of words trying to explain what shouldn’t need explanation, which says something about the human need to verbalize experiences.

Why Suprematism Art Still Matters

A century later, Suprematism art remains influential. Minimalist artists in the 1960s were definitely looking at Malevich. Contemporary designers reference Suprematist compositions. Every time someone makes a logo with simple geometric shapes, there’s a tiny echo of Suprematism there.

But more importantly, Malevich asked questions that still feel relevant: What is art’s essence? Can form and color communicate without representing anything? What happens when you strip everything away until only feeling remains? These aren’t settled questions, which is why people still argue about that black square.

Quick Takeaways

If you’ve made it this far, here’s what’s worth remembering about Suprematism art:

- Malevich founded the movement around 1913-1915 as a radical break from representational art

- The black square painted in 1915 became the iconic symbol and “zero point” of the movement

- Suprematism art focused on basic geometric forms painted in limited colors to express “pure feeling”

- The movement lasted roughly until the mid-1920s when Stalin’s government suppressed abstract art

- Key works include Black Square, White on White, and various dynamic compositions with floating shapes

- Influences ranged from Cubism and Futurism to Russian folk art and mystical philosophy

- Despite its short lifespan, Suprematism influenced modernist movements worldwide including Bauhaus and De Stijl

Looking Back at the Revolution

So yeah – Suprematism art was this wild moment when painting stripped itself down to almost nothing and then declared itself reborn. Was it pretentious? Absolutely. Was it revolutionary? Also yes.

The thing I’ve come to appreciate about Malevich is his conviction. He really believed that a black square could change how people perceive reality. Whether he was right is still up for debate. But he committed fully to the idea, even when it meant basically ending his career under Stalin’s regime.

We’re now over a hundred years past that first exhibition in Petrograd. Suprematism art hasn’t solved the world’s problems or unlocked cosmic consciousness like Malevich hoped. But every time someone creates something radically simple – whether it’s art, design, or music – and says “this is all you need,” they’re channeling a bit of that Suprematist spirit.

The movement burned bright and fast, then got snuffed out by politics. But its asking us to see differently, to feel without thinking, to find meaning in the supposedly meaningless – that project continues. Which is more then you can say for most art movements that crash and burn within a decade.

FAQs

What makes Suprematism art different from other abstract art movements?

Suprematism art strips visual elements down to the absolute basics – just geometric forms and flat colors, nothing else. While other abstract movements like Cubism still referenced real objects in fragmented ways, Suprematism eliminated all connections to the physical world. Malevich wanted pure abstraction that existed entirely on its own terms, focused on feeling rather than representation. The movement also had a mystical, almost spiritual quality that set it apart from more materially-focused movements like Constructivism.

Why did Malevich paint Black Square?

Malevich created Black Square as the “zero point” of painting – a complete reset of what art could be. He wanted to free art from representing the real world and instead focus on pure artistic feeling. The black square on white background was the simplest possible composition, stripped of all references to nature or objects. It was meant to be experienced emotionally rather than understood intellectually. Some scholars also point out that X-rays revealed earlier paintings underneath, suggesting the work evolved from earlier experiments rather then appearing fully formed.

How did the Russian Revolution affect Suprematism art?

Initially, the revolutionary atmosphere in Russia helped Suprematism thrive because artists felt empowered to break all the old rules and reimagine everything from scratch. The movement aligned with the revolutionary spirit of starting over completely. However, when Stalin rose to power in the mid-1920s, everything changed. The Soviet government wanted art that masses could easily understand and that promoted socialist values. Abstract art like Suprematism was seen as elitist and useless to the worker’s cause. By 1934, Socialist Realism was the only acceptable style, and Suprematism was effectively dead in Russia.

What is the “White on White” painting about?

“White on White” (1918) represents Malevich pushing Suprematism art to its logical extreme. It shows a white square painted in a slightly different shade of white than the background – you can barely see it. This was Malevich exploring how far he could reduce painting before it ceased to be art at all. The subtle tonal differences create a sense of the square floating in space. Some interpret it as representing infinite possibility or transcendence beyond the material world. Others see it as Malevich reaching the endpoint of his own philosophy, where painting almost disappears entirely.

How can I understand Suprematism art if I don’t “get it”?

Don’t worry about getting it intellectually – that’s not really the point. Malevich wanted people to experience Suprematism art emotionally and directly. Just look at the shapes and colors without trying to find hidden meanings. Notice how different forms make you feel – does a black square feel heavy or stable? Does a red circle feel energetic? Pay attention to how shapes seem to move or float in space. If you’re confused or even frustrated, that’s a legitimate response too. The worst thing you can do is pretend to see something profound when your honestly just seeing geometric shapes on a canvas.