Russian protest art has always been more than just paintings on walls or performances in public spaces. It’s a living, breathing form of resistance that has evolved through centuries of political change, artistic innovation, and human courage. From the hidden messages of Soviet-era artists to the bold digital creations of today’s activists, Russian artists have consistently found ways to speak truth to power through their creative work. What makes Russian protest art so compelling is how it transforms personal and political struggles into universal statements about freedom, justice, and human dignity. The artists behind these works often face tremendous risks – fines, arrests, or worse – yet they continue to create, driven by a belief that art can indeed change the world. For art lovers looking to understand this powerful movement, exploring Russian protest art offers not just aesthetic appreciation but a deeper connection to the universal human desire for expression and freedom. This journey through Russia’s creative resistance reveals how art becomes activism, and how creativity becomes courage in the face of oppression.

What Makes Russian Protest Art So Powerful?

Russian protest art packs a unique punch that sets it apart from other activist art movements around the world. Honestly, it’s not just about being controversial or shocking – though some of it definitely is. The real power comes from how deeply it’s woven into Russia’s complex relationship between art, politics, and everyday life. You see, in Russia, art has never really been allowed to exist in a bubble. It’s always been expected to serve some purpose, whether that’s promoting state ideology or, more interestingly for us, challenging it.

The strength of Russian protest art lies in its ability to speak multiple languages at once. There’s the literal message – say, anti-war slogans or political criticism – but then there’s this whole other layer of meaning that Russians instinctively understand. It’s like having a conversation where everyone knows what’s really being said beneath the surface. Take the way artists use symbols and references that might seem obscure to outsiders but hit home immediately with Russian audiences. This coded language developed out of necessity during Soviet times when direct criticism could land you in serious trouble, and it’s still going strong today.

What really gets me is how personal so much of this art is. Unlike some protest art that feels generic or detached, Russian protest art often carries the weight of real individual experiences and risks. When you look at a piece by someone like Pyotr Pavlensky or read about the street artists working in Russian cities right now, you’re not just seeing art – you’re seeing someone’s act of courage, their personal stand against something they believe is wrong. That authenticity resonates with people in a way that more abstract political statements sometimes don’t. It’s raw, it’s real, and it’s incredibly powerful because you know the artist has literally put themselves on the line to create it.

The Unique Blend of Art and Politics in Russian Culture

Russian culture has this fascinating thing where art and politics have always been tangled up together, sometimes in really uncomfortable ways. Unlike in some Western countries where art can exist pretty separately from politics, in Russia, the two have been doing this complicated dance for centuries. Think about it – from the icons that served both religious and political purposes in ancient Russia, to the propaganda art of the Soviet period, to today’s protest pieces, art has always been expected to take sides in one way or another.

This intense relationship means that Russian artists develop this really sophisticated understanding of how to use their work politically. They’re not just making pretty pictures or interesting sculptures – they’re engaging in a dialogue that’s been going on for generations. There’s this unspoken tradition they’re part of, this lineage of artists who’ve used their creativity to push back against whatever power structure happens to be in charge at the moment. It’s like they’re carrying forward a torch that’s been passed from one generation of dissident artists to the next.

What’s really cool is how this creates these unexpected connections across time periods. A contemporary street artist in Moscow might be using techniques or ideas that trace back to underground artists of the 1970s, who in turn were influenced by avant-garde artists from the early 20th century. There’s this continuity that gives Russian protest art depth and resonance that you don’t always find elsewhere. When you look at a piece of Russian protest art, you’re not just seeing a reaction to current events – you’re seeing the latest chapter in this long, ongoing story of artistic resistance.

From Tsars to Today: The Evolution of Russian Protest Art

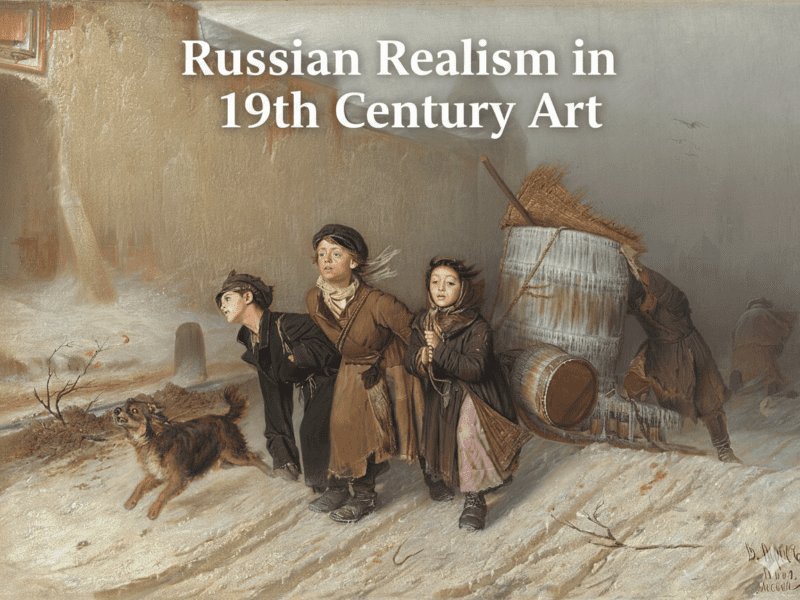

The story of Russian protest art didn’t just start yesterday – it’s been unfolding for centuries, each era adding its own chapter to this ongoing narrative of creative resistance. Way back in the 19th century, even under the strict censorship of the Tsars, artists found ways to embed criticism in their work. Painters like Ivan Kramskoy and the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) group created realistic depictions of ordinary Russian life that, while not explicitly political, highlighted social inequalities and the harsh realities faced by most Russians. Their art was a quiet form of protest, showing the truth of Russian society in a way that official art never would.

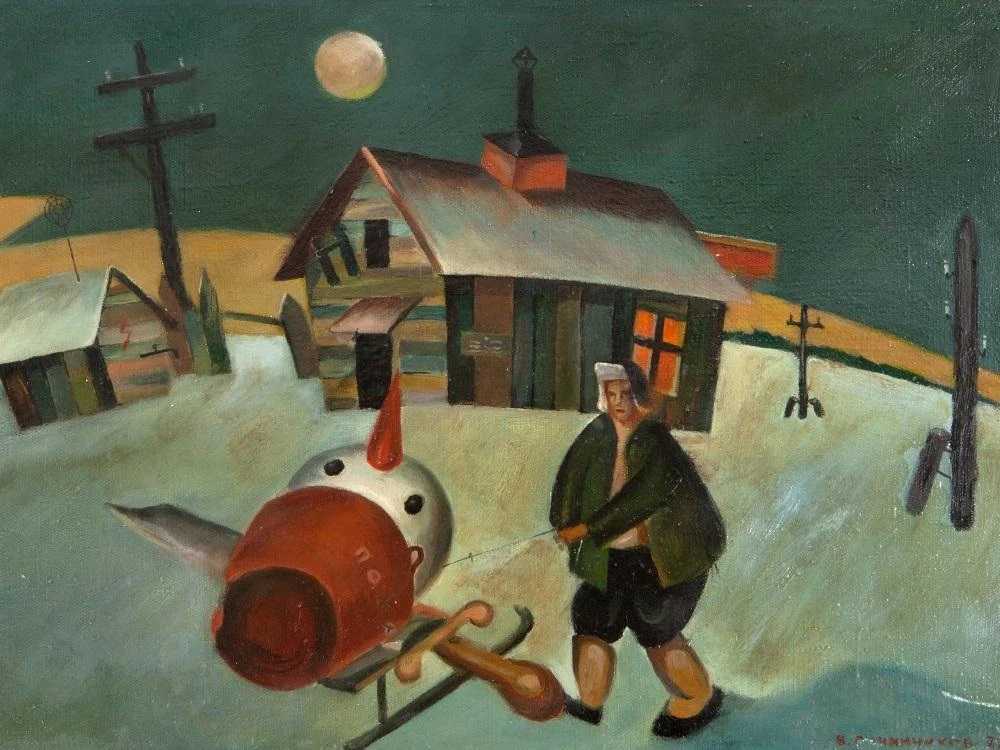

Then came the Russian Revolution and the early Soviet period, which is when things get really interesting. Initially, the avant-garde artists like Malevich and Tatlin were super excited about the revolution – they saw it as a chance to completely reinvent art and society. Their constructivist and suprematist works were revolutionary in both style and content, breaking all the rules of traditional art. But as the Soviet system became more rigid, especially under Stalin, the space for artistic experimentation shrank dramatically. Socialist realism became the only acceptable style, and artists who didn’t conform faced serious consequences. This is when Russian protest art really had to learn how to speak in code.

The Soviet era produced some incredibly clever forms of protest art. Artists developed this whole vocabulary of hidden meanings and symbols that could pass censorship but still convey critical messages to those in the know. It was like they were having a conversation that the authorities couldn’t quite understand. Some artists used abstract forms that were too obscure to be seen as threatening, while others embedded subtle critiques in seemingly innocent scenes. The fact that so much of this art survived and that artists continued to create despite the risks shows just how powerful the drive for artistic expression really is.

Early Roots: Art as Dissent in Imperial Russia

Looking back at Imperial Russia, you might think there wasn’t much room for protest art given the strict control the Tsars maintained, but you’d be surprised at how artists managed to push back even then. The Peredvizhniki movement of the 1860s-1880s is a perfect example. These artists broke away from the official art academy and started taking their exhibitions directly to the people, showing realistic paintings of Russian life that often highlighted social injustice. Works like Ilya Repin’s “Barge Haulers on the Volga” weren’t explicitly political, but they forced viewers to confront the harsh realities of life for ordinary Russians – which was pretty revolutionary in itself.

Literature was another avenue for protest, with writers like Pushkin, Gogol, and later Dostoevsky and Tolstoy using their works to critique Russian society. While not visual art, these literary protests influenced visual artists and helped create a culture where artistic expression could carry social and political weight. The satirical journals and cartoons that appeared in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were also forms of protest art, using humor and caricature to criticize the government and social conditions.

What’s fascinating about this period is how it laid the groundwork for later protest movements. The idea that art should serve a social purpose, that it should reflect reality and potentially inspire change – these concepts became deeply embedded in Russian artistic culture. Even though the methods and specific political contexts would change dramatically in the decades to come, this fundamental belief in art’s power to effect social change was established during the Imperial period and has continued to influence Russian artists ever since.

Soviet Era: When Art Had to Speak in Code

The Soviet period is when Russian protest art really had to get creative – and I mean that literally. With official censorship so strict and the consequences for dissent so severe, artists developed incredibly sophisticated ways to embed critical messages in their work. It was like they were writing in a secret language that only certain people could understand. The underground art scene that flourished despite (or maybe because of) these restrictions produced some of the most conceptually interesting protest art in Russian history.

Sots Art, which emerged in the 1970s, is a perfect example of this coded approach. Artists like Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid took the visual language of Soviet propaganda – the heroic workers, the optimistic slogans, the bright colors – and twisted it just enough to create works that critiqued the very system they appeared to celebrate. To the casual observer (or censor), their paintings might look like typical socialist realism, but to those paying attention, they were brilliant satires that exposed the gap between Soviet rhetoric and reality. It was this kind of clever double-speak that allowed artists to continue creating politically engaged work without getting themselves into too much trouble.

Other artists turned to abstraction or conceptual art as forms of resistance. By creating work that was formally innovative but didn’t contain obvious political imagery, they could claim their art was purely aesthetic while still making a statement about artistic freedom. The Moscow Conceptualist school, for instance, produced work that was often deeply philosophical and critical of Soviet ideology, but in such an oblique way that it was difficult for authorities to pin down exactly what was being criticized. This period really shows how necessity breeds creativity – when direct expression is forbidden, artists find infinitely more subtle and interesting ways to say what needs to be said.

Post-Soviet Explosion: New Freedoms, New Forms

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Russian artists suddenly found themselves in this totally new situation where they could, theoretically at least, say and create whatever they wanted. It was like being let out of a cage after decades of confinement, and the art scene exploded with all this pent-up creative energy. The 1990s was this wild, chaotic period where artists were experimenting with new forms, new media, and new ways of engaging with politics and society. Some of the most interesting Russian protest art came out of this time of transition.

Performance art really took off in a big way during this period. Artists like Oleg Kulik, who became famous for his performances where he acted like a dog, were pushing boundaries in ways that would have been unthinkable just a few years earlier. These performances weren’t just about shock value – they were exploring what it meant to be human, what it meant to be free, and how individuals related to society and authority in this new, uncertain Russia. The fact that artists could now do this kind of work openly, without fear of immediate arrest or worse, was revolutionary in itself.

But here’s the thing – with all this new freedom came new challenges. The art market developed, commercial pressures emerged, and artists had to figure out how to maintain their critical edge in a completely different environment. Some embraced the new opportunities, while others struggled with how to stay relevant when the clear enemy of Soviet censorship was gone. This tension between artistic freedom and commercial pressure, between critical engagement and market success, became a defining feature of the post-Soviet art scene and continues to influence Russian protest art today.

Digital Age: How Technology Changed Russian Protest Art

The rise of the internet and social media has completely transformed Russian protest art, creating new possibilities and new challenges for activist artists. Suddenly, artists could reach audiences directly without going through galleries, museums, or official channels. This democratization of distribution has been huge – an artist can create something today and have it seen by thousands of people around the world by tomorrow. The speed and reach of digital communication has made Russian protest art more global and more immediate than ever before.

Take Pussy Riot as probably the most famous example. Their punk performances in places like Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior were designed specifically to be filmed and shared online. They understood that the real impact wouldn’t come from the handful of people who might witness the performance live, but from the millions who would see it on YouTube and social media. This digital strategy has become increasingly common among Russian protest artists, who use platforms like Instagram, Telegram, and Twitter to share work that might be too risky to display publicly in Russia.

But digital technology hasn’t just changed how art is distributed – it’s changed what the art looks like too. Digital art, memes, video art, and online performances have all become important forms of Russian protest art. Artists are using new tools and techniques to create work that responds to current events in real time. When something happens politically in Russia, you can bet that artists are responding with digital creations within hours, if not minutes. This immediacy makes contemporary Russian protest art incredibly dynamic and responsive, but it also creates new vulnerabilities as authorities become more sophisticated at monitoring and controlling online spaces.

Meet the Artists: Faces Behind the Resistance

Behind every powerful protest movement are the people who put themselves on the line to make it happen, and Russian protest art is no exception. The artists who create this work aren’t just abstract figures – they’re real people with real stories, real fears, and real courage. Getting to know them makes the art feel more immediate and more meaningful. It’s one thing to look at a provocative piece of protest art; it’s another thing to understand the person who created it, what they were risking, and what they hoped to achieve.

What strikes me most about these artists is their diversity. They come from different backgrounds, work in different mediums, and have different approaches to political expression. Some are well-known internationally, while others work in relative obscurity. Some create bold, in-your-face pieces that leave no doubt about their political stance, while others work with subtlety and nuance, embedding their messages in layers of meaning that only reveal themselves upon closer inspection. This diversity is one of the strengths of Russian protest art – it’s not a monolithic movement but a rich ecosystem of different voices and perspectives.

Another thing that’s really important to understand is the level of risk these artists take on. In Russia today, creating politically charged art can lead to fines, arrests, imprisonment, or worse. Despite these risks, artists continue to create, driven by a belief in the power of art to make a difference and a refusal to be silenced. Their courage is humbling, and it’s what gives Russian protest art its moral force. When you look at their work, you’re not just seeing an artistic statement – you’re seeing an act of bravery.

The Performance Pioneers: Pussy Riot and Pavlensky

When you talk about Russian protest art, you can’t ignore Pussy Riot – they’ve probably done more to bring international attention to Russian protest art than any other group. Formed in 2011, this feminist punk collective burst onto the scene with their unauthorized performances in public spaces, always filmed and shared online. Their “Punk Prayer” performance in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior in 2012 made headlines around the world and led to the arrest and imprisonment of two members, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina. What made Pussy Riot so powerful wasn’t just their provocative actions but their clever use of music, performance, and digital media to create work that was both artistically interesting and politically potent.

Pyotr Pavlensky is another figure who’s impossible to overlook in any discussion of Russian protest art. His performance pieces are extreme and unsettling, designed to force viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about Russian society. In 2012, he sewed his mouth shut in protest against the prosecution of members of Pussy Riot and the band’s supporters. In 2013, he wrapped himself in barbed wire outside a legislative building. And in 2014, he nailed his scrotum to Red Square in a piece called “Fixation,” which he described as a metaphor for the apathy and political indifference of Russian society. These performances are obviously shocking, but they’re also incredibly thoughtful and conceptually rigorous. Pavlensky calls his work “political art” rather than protest art, emphasizing that he’s making serious artistic statements about power and freedom, not just staging protests for their own sake.

What both Pussy Riot and Pavlensky share is this understanding that performance art can be a powerful tool for political expression precisely because it’s so immediate and so difficult to ignore. Unlike a painting that can be removed from a gallery wall or a book that can be banned, a performance happens in real time, in real space, and often in places where it’s not supposed to happen. This element of risk and transgression is what gives their work its power, and it’s why they’ve become such important figures in the story of Russian protest art.

Street Art Warriors: Creating Change in Public Spaces

While performance artists like Pussy Riot and Pavlensky often grab international headlines, there’s this whole other world of Russian protest art happening on the streets and walls of Russian cities. Street artists are doing some of the most interesting and courageous protest work in Russia today, often working anonymously and at great personal risk. These artists use public spaces as their canvas, creating murals, stencils, and graffiti that challenge official narratives and offer alternative perspectives on current events.

Take the artist known as Zoom, who creates these really clever pieces that reference Russian folk tales and culture but subvert them to make political points. His work “Turnip” reimagines the classic Russian folk tale about cooperation with a nuclear explosion and skeletons – a pretty direct statement about where he sees current policies leading. Or consider Vladimir Ovchinnikov, an 85-year-old artist who was fined for drawing a little girl in Ukrainian colors with bombs falling nearby. Despite his age and the risks, he continues to create protest art in his small town, showing that this isn’t just a young person’s movement but something that spans generations.

What makes street art such a powerful form of protest in Russia is its accessibility. Unlike gallery art, which might only be seen by a limited audience, street art is out there in public for everyone to see. It’s democratic in that way – you don’t need a ticket or special knowledge to encounter it. Of course, this visibility also makes it risky for the artists, who often work quickly and anonymously to avoid detection. Many street artists have developed distinctive styles that allow them to communicate their message while maintaining some level of protection through anonymity. It’s this constant tension between visibility and safety that makes Russian street protest art so compelling.

The New Generation: Digital Artists and Online Activists

The newest wave of Russian protest art is happening online, where digital artists and online activists are using new technologies and platforms to create and share politically charged work. These artists often work under pseudonyms or anonymously, using digital tools to create pieces that can be shared instantly across social media and messaging apps. It’s a form of protest art that’s perfectly suited to our current moment – fast, responsive, and able to reach global audiences in real time.

Artists like Koin, who creates these grotesque portraits of Russian politicians as vampires and monsters, are primarily sharing their work through social media rather than traditional art spaces. This digital-first approach allows them to respond quickly to current events and to reach audiences both inside and outside Russia. Similarly, the art group Yav creates murals and street art but documents and shares their work online, extending its impact far beyond the physical location where it was created. Their piece “Window onto Europe,” which shows Europe boarded up with concrete splattered with blood, was seen by thousands more people online than could have seen it in person in St. Petersburg.

What’s really interesting about this new generation is how they’re blending traditional artistic skills with digital savvy. Many of these artists have formal art training but are choosing to work in digital spaces because that’s where they can have the most impact. They’re creating memes, digital collages, video art, and other forms that didn’t even exist a few decades ago. This evolution shows how Russian protest art continues to adapt and change, finding new ways to express dissent and connect with audiences as technology and society evolve. It’s proof that the spirit of resistance is alive and well in Russian art, just taking new forms for a new era.

How Russian Protest Art Actually Works

Understanding how Russian protest art actually functions requires looking beyond the surface of individual pieces to see the systems and strategies that make this form of activism effective. It’s not just about creating something provocative or critical – it’s about understanding how to communicate in an environment where free expression is limited and where there are real consequences for speaking out. Russian protest artists have developed incredibly sophisticated approaches to getting their messages across while protecting themselves and maximizing their impact.

One of the key things to understand is that Russian protest art operates on multiple levels simultaneously. There’s the immediate visual or conceptual impact of a piece – what you see or experience directly. Then there’s the political message, which might be obvious or subtly encoded. And there’s also the meta-commentary about the very act of creating protest art in Russia today. Good Russian protest art works on all these levels at once, creating work that’s visually interesting, politically potent, and self-aware about its own context and limitations.

Another important aspect is how these artists think about audience. They’re not just creating for other artists or for the international art world – they’re creating for ordinary Russians who might encounter their work on the street or online. This means they need to use visual languages and references that will resonate with people who might not have any formal art education. At the same time, they’re often creating for an international audience as well, aware that their work might be seen by people outside Russia who have very different cultural reference points. Balancing these different audiences is one of the tricky parts of making effective Russian protest art.

Secret Languages: Symbols and Codes in Protest Art

Russian protest artists have become masters of coded communication, developing visual languages that can convey critical messages while flying under the radar of censorship. This isn’t something new – it’s a tradition that goes back to the Soviet period when artists had to be incredibly clever about how they embedded criticism in their work. What’s fascinating is how these coded languages have evolved over time, adapting to new political contexts and new forms of media while maintaining their core function of allowing artists to speak truth to power in a way that’s not immediately obvious to authorities.

Take the use of symbols, for instance. Russian protest artists often draw on a rich vocabulary of cultural, historical, and religious symbols that carry layers of meaning for Russian audiences. The artist Misha Marker uses five asterisks (*****) in his work as a stand-in for the word “war,” which is heavily censored in Russia today. To those in the know, these asterisks immediately signal what he’s referring to, but to authorities, they might seem like an abstract design. Similarly, many artists use colors like blue and yellow (the Ukrainian flag colors) in subtle ways that Russian audiences will recognize but that might not be immediately obvious to censors.

References to Russian literature, history, and folklore are another common coding strategy. When Zoom reimagines the folk tale “The Gigantic Turnip” with nuclear explosions, he’s counting on Russian viewers’ familiarity with the original story to understand the political commentary. This kind of intertextual reference allows artists to create work that’s deeply rooted in Russian culture while still making contemporary political points. It’s a way of saying something new by referencing something old, creating a dialogue between past and present that enriches the work and makes it more resonant for Russian audiences.

Risk and Courage: What Artists Face When They Create

It’s impossible to really understand Russian protest art without acknowledging the very real risks that artists take when they create politically charged work. We’re not talking about hypothetical risks here – we’re talking about actual consequences that artists face on a regular basis. Fines, arrests, imprisonment, physical violence, exile – these are all things that Russian protest artists have to consider every time they decide to create and share their work. The courage it takes to continue creating under these circumstances is just staggering.

Let’s look at some concrete examples. Yelena Osipova, a 77-year-old artist often called “the conscience of St. Petersburg,” has been protesting Putin’s regime for two decades. She’s been fined and arrested multiple times, and in one instance, police confiscated her paintings and took her home after she displayed anti-war art on a public street. Vladimir Ovchinnikov, the 85-year-old artist mentioned earlier, was fined 35,000 rubles (about $475) for a drawing protesting the war in Ukraine – not a small amount for a pensioner in a small Russian town. These aren’t isolated incidents but part of a pattern of harassment and punishment that protest artists face regularly.

What’s remarkable is how artists continue to create despite these risks. Many of them talk about art as a form of personal survival, a way to process difficult emotions and maintain their humanity in the face of oppression. The artist Koin, who creates grotesque portraits of Russian officials, said he makes art because it helps him release “toxic emotions that poison me – anger, rage, fear, disgust.” This psychological dimension is crucial – for many artists, creating protest art isn’t just a political act but a necessary form of self-preservation and resistance against the dehumanizing effects of authoritarianism.

From Streets to Galleries: How Protest Art Goes Mainstream

One of the interesting dynamics in Russian protest art is how work that starts as underground, dissident expression often finds its way into mainstream galleries, museums, and the international art market. This journey from the margins to the mainstream raises all sorts of questions about what happens to protest art when it becomes commodified, when it’s bought and sold and displayed in institutions that are part of the very systems the art might be critiquing. It’s a complicated process that involves changes in context, audience, and meaning.

The Saatchi Gallery’s “Art Riot: Post-Soviet Actionism” exhibition is a perfect example of this phenomenon. The show featured artists like Pussy Riot, Pyotr Pavlensky, and Oleg Kulik – artists whose work began as illegal, transgressive actions in public spaces but was now being displayed in a major London gallery with all the institutional legitimacy that entails. Does this institutional recognition legitimize the art, or does it somehow neutralize its protest power? There’s no easy answer, but it’s a tension that runs through much of Russian protest art as it gains international attention.

What’s clear is that this journey from streets to galleries changes the work in significant ways. When protest art enters the institutional art world, it’s often removed from its original context and audience. A performance that was shocking and disruptive when it happened on Red Square takes on different meanings when it’s documented and displayed in a white cube gallery. The audience changes too – instead of being ordinary Russians encountering the work unexpectedly in public spaces, it becomes art world insiders who seek it out in institutional settings. These changes don’t necessarily invalidate the work, but they do transform it, creating new layers of meaning and interpretation.

Why This Matters Beyond Russia’s Borders

Russian protest art isn’t just a Russian phenomenon – it has relevance and resonance far beyond Russia’s borders. In an era where authoritarianism is on the rise globally, where freedom of expression is under threat in many countries, and where artists around the world are grappling with how to respond to political repression, the Russian experience offers valuable lessons and inspiration. The strategies Russian artists have developed for creating politically engaged work under difficult circumstances, their courage in continuing to create despite risks, and their innovative approaches to reaching audiences all have something to teach us about the relationship between art and politics in the 21st century.

There’s also this fascinating global dialogue happening in protest art today, where artists from different countries influence and inspire each other. Russian protest art has been influenced by international movements like street art, performance art, and digital activism, while also contributing its own unique perspectives and approaches to this global conversation. When Pussy Riot stages a punk protest in a cathedral, they’re drawing on a long tradition of Russian dissent but also connecting with global feminist and anti-authoritarian movements. This cross-pollination of ideas and tactics makes contemporary protest art a truly global phenomenon, with Russian artists playing an important role in shaping its evolution.

And let’s not forget the practical aspect: Russian protest art often serves as a crucial source of information and perspective for people outside Russia who want to understand what’s really happening in the country. In an era of state-controlled media and disinformation, art can sometimes tell the truth more effectively than journalism. The images, performances, and digital creations coming from Russian protest artists provide windows into Russian society that are more nuanced and human than what we typically get from news reports. For art lovers around the world, engaging with this work isn’t just an aesthetic experience – it’s a way to connect with the human reality of life in Russia today.

Global Influence: How Russian Art Inspires Worldwide Activism

The influence of Russian protest art extends far beyond Russia’s borders, inspiring artists and activists around the world who are fighting against authoritarianism and for freedom of expression. The courage and creativity of Russian artists have become a reference point for protest movements globally, showing how art can be a powerful tool for political resistance even in the most challenging circumstances. When artists in other countries face repression, they often look to the Russian example for strategies and inspiration.

Take the global impact of Pussy Riot, for instance. Their 2012 performance and subsequent trial sparked international solidarity actions, with artists and activists around the world organizing support events and creating response pieces. But more importantly, their approach – combining music, performance, digital media, and feminist politics – has influenced protest art movements globally. Artists in countries from Turkey to Thailand to the United States have adopted similar tactics, using unauthorized performances in public spaces, documenting them for online distribution, and leveraging social media to amplify their message. This isn’t direct imitation but rather inspiration – seeing what’s possible and adapting those ideas to local contexts.

Russian protest art has also contributed significantly to global conversations about the relationship between art and politics. The theoretical and conceptual rigor of artists like Pavlensky, the coded communication strategies developed during the Soviet era, the innovative use of digital media by contemporary artists – all of these have enriched global discourse about politically engaged art. Russian artists have shown that protest art doesn’t have to be didactic or aesthetically simplistic; it can be conceptually complex, formally innovative, and politically potent all at once. This has raised the bar for protest art globally, pushing artists to develop work that’s both artistically sophisticated and politically effective.

What Art Lovers Can Learn from Russian Protest Art

For art lovers looking to deepen their understanding and appreciation of art, Russian protest art offers some incredibly valuable lessons. First and foremost, it teaches us to look beyond the surface of artworks to consider their context and the risks involved in their creation. When we understand that an artist might have faced arrest or worse for creating a piece, it changes how we engage with that work. We’re not just looking at an object or image; we’re witnessing an act of courage and defiance. This awareness makes the experience of looking at art more immediate and more meaningful.

Russian protest art also teaches us about the power of visual language and symbolism. These artists are masters of communication, able to convey complex political ideas through visual means that can reach people across linguistic and cultural barriers. For art lovers, studying how Russian artists use symbols, references, and visual metaphors can deepen our appreciation of how art communicates. It helps us become more attentive viewers, more aware of the layers of meaning that can be embedded in visual work. This skill isn’t just relevant for understanding protest art – it enhances our ability to engage with all forms of visual art.

Perhaps most importantly, Russian protest art reminds us that art can be more than just decoration or entertainment – it can be a vital form of human expression and a force for social change. In a world where art is often commodified and stripped of political content, Russian protest art stands as a powerful reminder of art’s potential to matter, to make a difference, to speak truth to power. For art lovers, engaging with this work can be transformative, challenging us to think more critically about the role of art in society and our own responsibilities as consumers and supporters of art.

Getting Involved: How to Engage with Russian Protest Art

So you’re interested in Russian protest art and want to engage with it more deeply – where do you start? The good news is that there are more ways than ever to discover, explore, and support this important work, whether you’re in Russia or anywhere else in the world. From online exhibitions to social media follows, from gallery shows to academic studies, there are multiple entry points for art lovers who want to connect with Russian protest art and the artists who create it. The key is knowing where to look and how to engage responsibly and ethically.

One thing to keep in mind as you explore this world is that Russian protest art exists in a complex political context. Many artists are working under difficult circumstances, and some may be at risk because of their work. This means that as consumers and supporters of this art, we need to be thoughtful about how we engage with it – respecting artists’ safety, being aware of the potential consequences of sharing certain works, and understanding that what might seem like innocent appreciation from our perspective could have serious implications for the artists themselves. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t engage – quite the opposite – but it does mean we should do so with awareness and care.

Another important consideration is that Russian protest art is incredibly diverse, encompassing many different styles, mediums, approaches, and political perspectives. Not all Russian protest artists agree with each other, and they don’t all use the same tactics or have the same goals. As you explore this world, keep an open mind and be willing to engage with work that might challenge your assumptions or push you out of your comfort zone. The richness and diversity of Russian protest art is part of what makes it so valuable and interesting.

Where to Find Russian Protest Art Today

If you’re looking to discover Russian protest art, there are several great places to start your exploration. Online platforms are probably the most accessible entry point, especially for international audiences. Social media platforms like Instagram and Telegram have become crucial spaces for Russian protest artists to share their work. Following artists directly, or following curators and galleries that specialize in Russian art, can give you a real-time view of what’s being created. Many artists use pseudonyms or anonymous accounts for safety reasons, so you might need to do a bit of digging to find them, but that’s part of the adventure.

Museums and galleries outside Russia have also been important venues for discovering Russian protest art. Institutions like the Saatchi Gallery in London, the Tretyakov Gallery (though access has become more complicated recently), and various contemporary art museums around the world have hosted exhibitions of Russian protest art. These shows provide valuable context and curation, helping viewers understand the historical and cultural significance of the work. Keep an eye on exhibition schedules at contemporary art museums – Russian protest art is having a moment internationally, so there are often shows to discover.

Academic and journalistic sources are another great way to engage with Russian protest art. Scholars who specialize in Russian art and politics often publish insightful analyses that can deepen your understanding of specific works or movements. Art journals, cultural magazines, and even mainstream media outlets frequently cover Russian protest art, especially during moments of political tension. These written sources can provide context and interpretation that enriches your direct experience of the art itself. The key is to seek out diverse perspectives – don’t just rely on one source or one type of analysis.

Quick Takeaways

- Russian protest art has evolved over centuries, adapting to political changes while maintaining its core mission of creative resistance.

- Artists use coded languages and symbols to communicate critical messages while avoiding censorship and repression.

- Digital technology has transformed how Russian protest art is created and shared, enabling global reach and real-time responses.

- The personal risks artists take – fines, arrests, imprisonment – give their work moral force and authenticity.

- Russian protest art influences global activism movements while being shaped by international artistic trends.

- Engaging with this art requires awareness of its political context and respect for artists’ safety and autonomy.

Conclusion

Exploring Russian protest art reveals something profound about the relationship between creativity and resistance. What I’ve learned the hard way is that this isn’t just about politics or aesthetics – it’s about the fundamental human need to express truth even when doing so is dangerous. The artists we’ve looked at aren’t just making statements; they’re putting their lives and freedom on the line every time they create and share their work. That kind of courage changes how you see art entirely.

The evolution from Soviet-era coded messages to today’s digital activism shows how adaptable and resilient this tradition of creative resistance really is. Russian artists keep finding new ways to speak truth to power, new languages to express dissent, new platforms to reach audiences. They’re not just reacting to current events – they’re participating in a centuries-long conversation about freedom, justice, and human dignity that happens through art rather than around it.

For art lovers, engaging with Russian protest art offers more than just visual stimulation or intellectual interest. It offers a connection to something real and urgent, a reminder that art can matter in the most concrete ways possible. When we look at these works, we’re not just seeing objects or images – we’re witnessing acts of courage that deserve our attention, our respect, and our support.

FAQs

Q – What is Russian protest art?

A – Russian protest art refers to creative works that express political dissent or social criticism, created by Russian artists using various mediums including performance, street art, digital media, and traditional forms.

Q – How do Russian protest artists avoid censorship?

A – Artists use coded symbols, abstract forms, digital platforms, anonymous identities, and international distribution to bypass censorship while still conveying critical messages to audiences.

Q – Who are some famous Russian protest artists?

A – Notable figures include Pussy Riot, Pyotr Pavlensky, Oleg Kulik, and contemporary street artists like Zoom, Misha Marker, and members of the art group Yav.

Q – What risks do Russian protest artists face?

A – Artists risk fines, arrests, imprisonment, physical violence, exile, and having their work destroyed or confiscated by authorities for creating politically charged art.

Q – How can I support Russian protest artists?

A – Support artists by following their work online, purchasing through reputable galleries, amplifying their messages safely, and supporting organizations that defend artistic freedom and human rights.