When Art Becomes the State’s Voice: Socialist Realism Exposed

Art has always been political, but rarely has it been so openly weaponized as a tool for mass control. Socialist realism transformed creative expression into state-sponsored propaganda, turning artists into what Stalin called “engineers of souls.” This movement, which dominated the Soviet Union for over 50 years, reveals how governments can manipulate culture to shape entire societies.

The story of socialist realism isnt just about art – it’s about power, control, and the price of creative freedom under totalitarian rule.

The Birth of State-Controlled Art

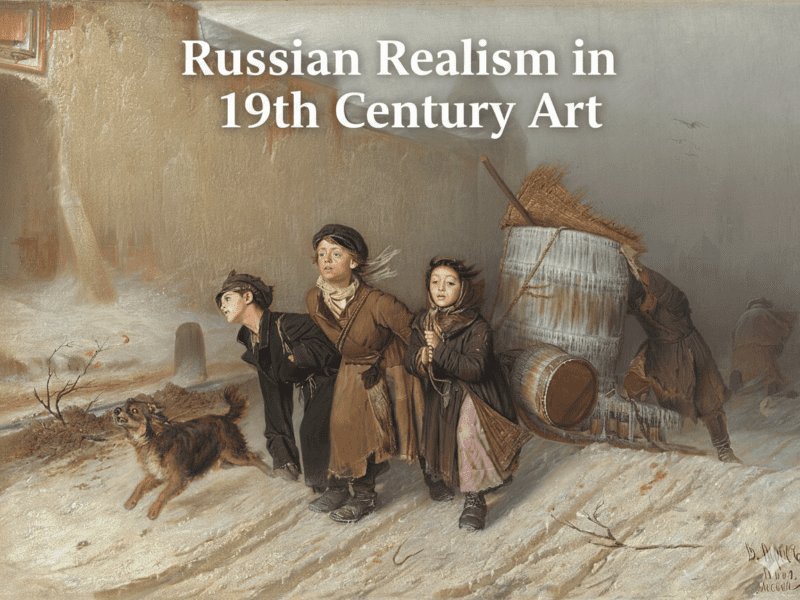

Soviet art didn’t start as propaganda. After the 1917 revolution, there was actually this brief, exciting period where Russian artists could experiment with all sorts of avant-garde styles. Futurists were creating wild abstract pieces, traditionalists stuck to realistic portrayals, and everyone was debating what Soviet art should look like.

But by 1928, when Stalin consolidated power, that artistic freedom got crushed pretty fast. The government shut down private art enterprises and forced all artists into state employment. The Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, founded in 1922, began pushing for art that depicted “everyday life among the working people” – and that was just the beginning.

On April 23, 1932, the Central Committee made socialist realism the official artistic mandate. The term itself was first used by Ivan Gronsky in Literaturnaya Gazeta on May 23, 1932, and Stalin himself approved it in high-level meetings.

What Made Socialist Realism So Different

Here’s where things get interesting – and disturbing. Socialist realism wasnt about showing life as it really was. Instead, it had to show life “as it should be” under socialism. This meant painting happy, muscular workers in spotless factories and depicting peasants who looked like Olympic athletes rather than the often malnourished reality.

The movement had four specific guidelines that artists had to follow:

Proletarian: Art had to be easily understood by workers. No abstract nonsense or intellectual complexity allowed.

Typical: Scenes should show everyday people doing everyday things – but idealized versions of both.

Realistic: Despite the idealization, it had to look photographically real. No stylistic experimentation.

Partisan: Everything had to support the Communist Party and state goals. No exceptions.

The annoying thing about these rules is how they contradict themselves. How can something be both “realistic” and completely idealized? That contradiction is exactly what made socialist realism so artificial and, ultimately, so creatively stifling.

The Artists Who Survived (And Those Who Didn’t)

Working as an artist under socialist realism was like walking through a minefield blindfolded. Over 300 writers were executed or prevented from publishing during the 1930s alone. Painters like Mykhailo Boichuk, Sofiia Nalepinska, and Ivan Padalka were shot. The Berezil theater was liquidated, its founder Les Kurbas died in a prison camp, and major actors were imprisoned.

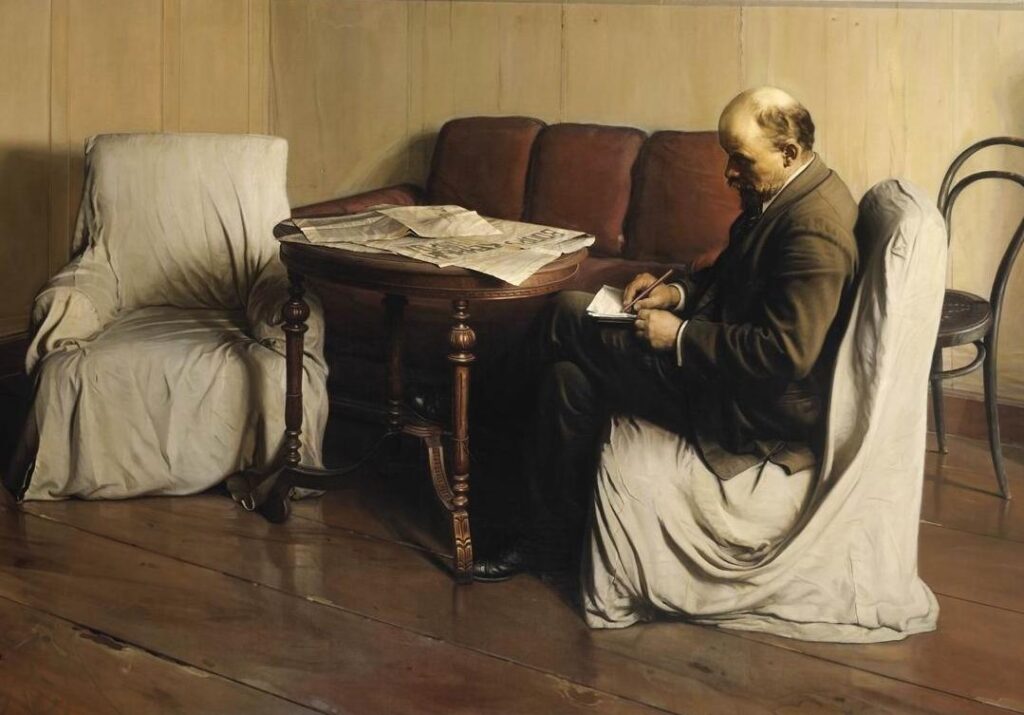

Some artists managed to navigate the system. Isaak Brodsky became incredibly successful with works like “Lenin in Smolny” (1930), which was reproduced millions of times and hung in Soviet institutions everywhere. The painting shows Lenin working alone at night, surrounded by empty chairs – creating this mythology of the selfless leader sacrificing for his people.

Yuri Pimenov’s “Increase the Productivity of Labour” (1927) shows five stoic workers facing blistering flames in a steel factory, bare-chested but unwavering. It’s propaganda, sure, but there’s still some artistic experimentation in the slightly abstract figures and Cubo-Futurist background elements.

By the 1940s and 1950s, though, even these small creative freedoms disappeared. A younger generation of artists who’d been born into Soviet rule produced increasingly rigid, formulaic works. Some tried to maintain individuality through lighting effects or impressionist techniques, but the overall aesthetic became stifling.

I learned this when researching Soviet art collections – many of the most interesting pieces from this era were never displayed publicly and only surfaced decades later.

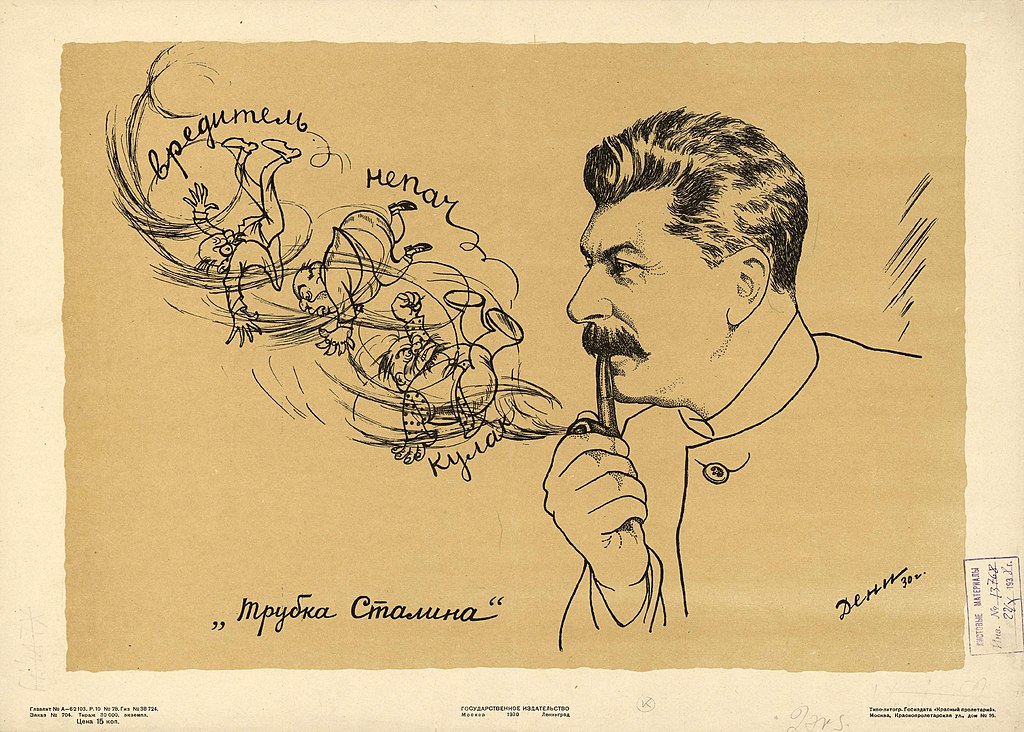

The Propaganda Machine in Action

Socialist realism wasn’t just about individual artworks; it was a comprehensive system of cultural control. The state became the sole patron of the arts, employing artists as civil servants who received salaries and benefits in exchange for absolute creative obedience.

Art schools emphasized traditional techniques like drawing from life models, but only within approved subjects and styles. Students learned to paint workers, farmers, soldiers, and party leaders – always young, healthy, and optimistic. The “New Soviet Man” became the ideal subject: physically perfect, morally pure, and completely devoted to socialist goals.

The themes were remarkably consistent across thousands of works. Glorification of manual labor appeared everywhere, with exaggerated physiques emphasizing workers’ strength and dedication. Factory scenes, agricultural work, and construction projects dominated, always showing cooperation and collective effort rather than individual achievement.

Stalin’s cult of personality found perfect expression through socialist realist portraits. Artists produced countless heroic images of the leader, usually alone or with Lenin, presented as the wise father figure guiding the Soviet people toward a bright future.

The International Spread

Socialist realism didn’t stay confined to the Soviet Union. After World War II, as the USSR gained control over Eastern and Central Europe, the artistic style spread throughout the Eastern Bloc. Each country adapted it to local conditions while maintaining the core principles.

In China, socialist realism merged with traditional art forms, creating unique hybrid styles. Chinese propaganda posters from the 1950s and 1960s used socialist realist techniques to promote Mao’s policies, but incorporated Chinese aesthetic elements like composition and color palettes.

North Korea, Cuba, and other socialist states developed their own versions, each reflecting local revolutionary history and national identity while adhering to the basic formula of idealized realism in service of state ideology.

The movement’s influence extended beyond communist countries. During the Great Depression, American social realist artists borrowed techniques from socialist realism, though without the rigid state control. The Works Progress Administration employed artists to create murals and posters that celebrated American workers and democratic values.

The Creative Resistance

Despite the severe restrictions, some artists found ways to subvert the system. They used approved subjects but added subtle elements of dissent – a shadow that suggested melancholy, a facial expression that hinted at doubt, or compositional elements that could be read as ironic.

The underground art movement that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s operated through samizdat (self-publication) and tamizdat (publication abroad). Artists circulated forbidden works privately, creating an alternative culture that challenged official aesthetics.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev’s “thaw” allowed slightly more creative freedom. Artists began experimenting with form and content within the socialist realist framework, leading to works that maintained official approval while expressing more complex human emotions.

The Decline and Legacy

By the 1980s, socialist realism was losing its grip on Soviet culture. Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost policies allowed artists to openly criticize the movement’s limitations. Many artists who had worked within the system for decades finally admitted their frustration with the creative constraints.

The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked the end of socialist realism as an official artistic doctrine. Museums began displaying previously banned avant-garde works, and artists gained the freedom to explore whatever styles and subjects they chose.

Today, socialist realism occupies a complex place in art history. Some scholars argue it deserves serious aesthetic consideration, pointing to technically accomplished works that succeeded despite ideological constraints. Others maintain that political control inevitably corrupts artistic integrity.

The movement’s legacy raises uncomfortable questions about the relationship between art and power that remain relevant today. When governments, corporations, or social movements pressure artists to create works supporting specific messages, are we seeing echoes of socialist realism?

The Human Cost of Artistic Control

Looking back at socialist realism, what strikes me most is the human cost. Hundreds of talented artists, writers, and performers were silenced, imprisoned, or killed for refusing to conform. Others spent their careers creating works they privately despised, their creativity channeled into serving state propaganda rather than exploring human truth.

The movement also demonstrates how quickly artistic freedom can disappear. Within just a few years, the Soviet Union transformed from a society with vibrant artistic experimentation to one where deviation from official style could mean death.

Leon Trotsky, Stalin’s rival, was among the earliest critics of this rigid approach. He viewed cultural conformity as an expression of Stalinism in which “the literary schools were strangled one after the other.” Trotsky argued that socialist realism was “an arbitrary construct of the Stalinist bureaucracy” rather than a genuine artistic movement.

Modern Relevance and Lessons

Socialist realism may seem like ancient history, but its techniques for using art as propaganda remain surprisingly relevant. Contemporary governments, movements, and institutions still attempt to control artistic expression to promote specific messages.

The movement’s emphasis on accessibility – creating art that ordinary people could understand and appreciate – raises ongoing debates about elitism in contemporary art. While socialist realism’s methods were oppressive, its goal of connecting with mass audiences touches on real issues in today’s art world.

Digital technology has created new possibilities for both artistic freedom and control. Just as socialist realism used traditional media to spread state messages, modern propaganda can use social media, video games, and virtual reality to shape public opinion.

The recent trend of governments and institutions pressuring artists to create works promoting certain political or social messages echoes socialist realism’s basic premise that art should serve ideology rather than individual expression.

Understanding the Artistic Paradox

Socialist realism created a fundamental paradox that still resonates today. The movement claimed to represent “the people” while being imposed by an elite bureaucracy. It promised to show “reality” while depicting highly idealized fantasy. It celebrated creativity while crushing creative freedom.

This contradictory nature extended to its artistic techniques. Socialist realist works often displayed impressive technical skill – the artists were genuinely talented professionals who could paint realistic figures and compelling compositions. But that skill was channeled into creating images that served political purposes rather than exploring artistic possibilities.

The movement produced thousands of works that are visually striking and historically significant, even if they lack the creative freedom we associate with great art. Some pieces succeeded despite their constraints, creating genuine emotional impact through the artists’ sincere commitment to their craft.

The End of an Era

When the Soviet Union collapsed, many socialist realist works were removed from public display, rolled up and stored away like political prisoners being sent to Siberia – an ironic echo of what happened to impressionist and post-impressionist works in the 1930s.

Today, museums and galleries are reconsidering these works, not as great art but as important historical documents that reveal how totalitarian societies use culture to maintain control. The paintings and sculptures that once hung in places of honor now serve as warnings about the dangers of state-controlled expression.

Socialist realism ultimately failed because it tried to reduce the complexity of human experience to simple political formulas. Art, at it’s best, explores ambiguity, contradiction, and individual truth – exactly what socialist realism was designed to eliminate.

Quick Takeaways

- Socialist realism dominated Soviet art from 1932 to the 1980s, transforming artists into state employees who created propaganda rather than personal expression

- Over 300 writers were executed or banned during the 1930s for refusing to conform to official artistic guidelines

- The movement required art to be proletarian, typical, realistic, and partisan – creating an inherent contradiction between realism and idealization

- Artists like Isaak Brodsky found success within the system, while others were imprisoned or killed for resistance

- The style spread internationally through communist countries, each adapting it to local conditions while maintaining core propaganda functions

- Underground resistance movements emerged, using samizdat and tamizdat to circulate forbidden works privately

- The movement’s legacy raises ongoing questions about the relationship between art, politics, and creative freedom in contemporary society

Socialist realism stands as one of history’s most comprehensive attempts to control artistic expression. While it produced some technically accomplished works, its ultimate legacy is a cautionary tale about what happens when creativity serves ideology rather than human truth. For art lovers today, understanding this movement provides crucial context for recognizing and resisting similar attempts to weaponize culture for political ends.

The story of socialist realism reminds us that artistic freedom isn’t guaranteed – it must be actively protected. When we see governments, institutions, or movements demanding that artists create works supporting specific messages, we should remember the Soviet artists who paid with their careers, their freedom, and sometimes their lives for refusing to let their creativity become a tool of oppression.

FAQs

What’s the main difference between social realism and socialist realism? Social realism depicts real social conditions and problems, often critically, while socialist realism shows idealized versions of life under socialism. Social realism can be pessimistic and critical; socialist realism was required to be optimistic and supportive of the state. Think of social realism as showing workers as they really were – sometimes struggling or suffering – while socialist realism showed them as healthy, happy, and productive.

How did artists actually survive financially under socialist realism? Artists became state employees who received regular salaries, benefits, and housing from the government. They didnt sell work to private collectors but instead received commissions for public buildings, monuments, and official publications. This system provided security but eliminated artistic independence, since artists who didn’t follow official guidelines could loose their jobs and face imprisonment.

Were there any successful artistic works created under socialist realism? Yes, despite the constraints, some works succeeded artistically. Nikolay Ostrovsky’s “How the Steel Was Tempered” remains widely read because the author’s personal experience gave the story genuine emotional power. Some visual artists found ways to create compelling works within the system by focusing on technical excellence and subtle subversion. However, most scholars argue that the greatest artistic achievements came from underground resistance movements.

Did socialist realism influence art outside communist countries? Absolutely. During the Great Depression, American artists borrowed socialist realist techniques for Works Progress Administration murals and posters. Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera incorporated similar approaches to promote social justice. Even Nazi Germany used comparable methods for propaganda art. The movement’s emphasis on accessible, narrative art influenced democratic societies, though without the rigid state control.

How do we evaluate socialist realist artworks today? Modern museums and scholars approach these works primarily as historical documents rather than aesthetic achievements. They’re valuable for understanding how totalitarian societies use culture for control, and some pieces display impressive technical skill. However, most art historians argue that political constraints prevented genuine artistic innovation. The works are more important for what they reveal about power and propaganda then for their creative merit.

Tags: Soviet art, political propaganda, art history

Keyword used = socialist realism

SEO meta description: Discover how socialist realism transformed Soviet artists into propaganda tools. Explore the art movement that prioritized politics over creativity for 50+ years.